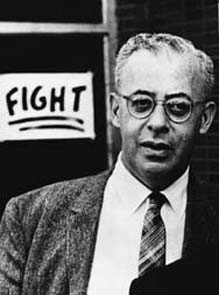

Saul Alinsky (1909-1972) was a leading political activist and theorist, social critic, self-described “radical,” and an architect of the modern Left’s structure and approach to advocacy and electioneering. Alinsky pioneered “community organizing,” a form of coalition-building centered on aligning the common goals of multiple interest groups too small or electorally weak to command a legislative majority. 1 He also invented the tactic of using shareholder activism to pressure publicly held companies into adopting “social justice” policies, today a common practice on the Left. 2

He is perhaps best-known for his 1971 book Rules for Radicals, an influential primer for left-of-center activists to achieve social change in which Alinsky facetiously lauded Lucifer (also known as the Devil in Christianity) as “the first radical known to man who rebelled against the establishment and did it so effectively that he at least won his own kingdom.” 3 Rules for Radicals has been credited for shaping the strategy and thinking of prominent liberals, socialists, and left-progressive activists of various schools. Hillary Clinton (then known as Hillary D. Rodham), a future U.S. Senator from New York, 2016 Democratic presidential nominee, and wife of President Bill Clinton, wrote her undergraduate thesis on Saul Alinsky in 1969 while attending Wellesley College in Massachusetts. 4

Alinsky is also remembered for his rough, uncompromising approach to politics. The “Alinsky-type protest,” observed the New York Times in 1966, is “an explosive mixture of rigid discipline, brilliant showmanship, and a street fighter’s instinct for ruthlessly exploiting his enemy’s weakness.” 5 A fellow activist and friend once described him as “smart and mean . . . deliberately insulting and provocative” but “erudit[e]” and “unconventional.” His primary biographer, Sanford D. Horwitt, calls Alinsky “a serious man, a driven man,” a “swashbuckling Renaissance man of independent thought and action, fearless, engagingly blunt, passionate but without sentimentality.” 6

Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF), formed in 1940, is still active in promoting liberal activism. The California labor leader Cesar Chavez was trained by the IAF in the 1950s. 7 IAF and Alinsky also trained and inspired numerous other center- and far-left political activists still active today, including leaders of the radical socialist Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the founders of the now-defunct ACORN. Faith In Action (formerly PICO National Network) remains among the largest faith-based advocacy groups based on Alinsky’s model.

Biography

Early Life (1909-1926)

Saul Alinsky was born in January 1909 in Chicago, Illinois, to Benjamin and Sarah Alinsky, the former an Orthodox Jewish immigrant from Russia. The Alinskys were initially very poor; as a small child, Saul and his family lived in the Maxwell Street section of Chicago, a neighborhood largely populated by Eastern European Jews from the 1880s to the 1920s which he later described as “one of the worst slums” in the city. By the time Saul was six years old, the Alinskys relocated to a new apartment in a wealthier part of the city before Sarah and Benjamin divorced, the latter moving to California. For the remainder of his childhood Saul grew up in relative affluence but had little serious contact with his father. 8

University of Chicago (1926-1930)

In 1926, Alinsky was admitted to the University of Chicago. Alinsky was noted for his mediocrity during his first two years in university, receiving no grade higher than a C and failing his American history course, landing him on academic probation. The future father of community organizing took no interested in organized campus life and was “something of a loner,” according to one of his biographers, remembered as “outgoing, interesting, opinionated, glib, sharp-tongued, [and] profane.” 9

In his junior year in 1928, Alinsky enrolled in a social pathology course taught by Ernest Watson Burgess, a highly influential thinker who headed the country’s first sociology department at the University of Chicago and shaped the field beginning in the 1920s. The main interest of the early sociologists was identifying the causes of extreme poverty and crime; Watson notably shifted the blame from immigrant heredity—a theory popularized by eugenicists—to social disorganization brought on by a lack of assimilation to American culture. Alinsky himself was fascinated by sociology and field studies in particular, and he excelled at “schmoozing” with and coaxing information out of strangers as part of his study of local dance halls, a popular meeting place for young Americans in the 1920s. 10

Associations with the Chicago Mob

In his senior year at the University of Chicago, Alinsky decided to write his thesis on mobster Al Capone and the Chicago Mafia, just prior to Capone’s conviction for tax evasion in 1931. Alinsky later recounted meeting “Big Ed” Stash, a “professional assassin who was the Capone mob’s top executioner”: 11

“He was drinking with a bunch of his pals and he was saying, “Hey, you guys, did I ever tell you about the time I picked up that redhead in Detroit?” and he was cut off by a chorus of moans. “My God,” one guy said, “do we have to hear that one again?” I saw Big Ed’s face fall . . . And I reached over and plucked his sleeve. “Mr. Stash,” I said, “I’d love to hear that story.” His face lit up. “You would, kid?” He slapped me on the shoulder. “Here, pull up a chair.” . . . And that’s how it started.”

Alinksy studied the Chicago Mob over the course of two years, and although he never met nor saw Capone himself, he gained intimate contacts in Capone’s outfit. “Big Ed” Stash introduced Alinsky to Frank Nitti, “the Enforcer” and de facto head of Capone’s organization after Capone’s conviction. Alinsky described mafia practices in sociological terms. For example, Nitti’s practice of hiring out-of-town killers for local hits to avoid emotional problems for murderers on his payroll Alinsky identified as a “primary relationship.” 12

“Once, when I was looking over their records, I noticed an item listing a $7,500 payment for an out-of-town killers. I called Nitto over and I said, “Look, Mr. Nitti, I don’t understand this. You’ve got at least twenty killers on your payroll. Why waste that money to bring somebody in from St. Louis?”

Frank was really shocked by my ignorance. “Look, kid,” he said patiently, “sometimes our guys might know the guy they’re hitting, they may have been to his house for dinner, taken his kids to the ball game, been the best man at his wedding, gotten drunk together. But you call in a guy from out of town, all you’ve got to do is tell him, ‘Look, there’s this guy in a dark coat on State and Randolph; our boy in the car will point him out; just go up and give him three in the belly and fade into the crowd.’ So that’s a job and he’s a professional, he does it. But one of our boys goes up, the guy turns to face him and it’s a friend, right away he knows that when he pulls the trigger there’s gonna be a widow, kids without a father, funerals, weeping—Christ, it’d be murder.””

“That was the reason they used out-of-town killers. This is what sociologists call a “primary relationship.” They spend lecture after lecture and all kinds of assigned reading explaining it. Professor Nitti taught me the whole thing in five minutes.”

Alinsky’s relationship to the Chicago Mob continued throughout his life, occasionally to his advantage. As late as the 1950s, Alinsky used his criminal contacts to call off labor union pickets in front of a drug store owned by his mother’s third husband. 13

Personal Life and Death

Alinsky met his wife, Helene Simon, while attending the University of Chicago in 1926, and they were married in June 1932. They adopted two children, Kathryn and Lee David. 14 In summer 1947, Helene and their children vacationed at Lake Michigan while Saul travelled for work. While swimming, Helene drowned in Lake Michigan likely while attempting to rescue her children from an undertow. 15 Alinsky remarried in 1952 to Jean Graham, the ex-wife of a Bethlehem Steel executive. 16

Saul Alinsky died of a heart attack in Carmel, California, on June 12, 1972, shortly after publishing his final book, Rules for Radicals (1971). His body was cremated without a funeral service. 17

Activist Career

Studying Criminology (1931-1935)

In late 1931, Alinsky took a job as a graduate student researcher with the Illinois Division of the State Criminologist’s Institute for Juvenile Research, where he studied the causes of juvenile delinquency. This brought him into close contact with the Sholto Street gang, a group of young boys and men from Chicago’s poor Italian immigrant community involved in crime ranging from petty theft to holdups and even a police shoot-out. Alinsky encouraged the gang members to record their stories and when they began committing crimes in order to establish when they began to fall into that lifestyle. His research was joined to that of sociologists E.W. Burgess and Clifford Shaw to argue for the existence of “high delinquency areas” in cities that remained such even when one immigrant group was replaced by another, indicating that the reasons the Sholto Street and other gangs turned to crime had less to do with ethnic characteristics and more with family life and environment. 18

In 1933, Alinsky was sent to continue his criminal behavior studies at the now-closed Illinois State Penitentiary in Joliet, a Chicago suburb. While there he was tasked with determining whether the infamous Chicago Irish Mafia boss Roger “the Terrible” Touhy should serve his 99-year sentence in the decrepit prison in Joliet or the state’s then-newly built Stateville Correctional Center, which Alinsky described as “comparable to the difference between a modern apartment house and an old convict ship.” In a private interview, Touhy attempted to bribe Alinsky with $20,000 (about $418,000 in 2021 dollars) to send him to Stateville. Alinsky refused. The following day Alinsky was approached by one of Touhy’s thugs, who threatened the sociologist’s life if he did not send Touhy to Stateville. Alinsky again refused the demand (although Touhy eventually was sent to Stateville anyway). 19

Alinsky left Joliet prison in 1936 to return to the Institute for Juvenile Research, telling friends that he was fired after he “physically attacked a prison guard in an angry rage” after witnessing the man’s “sadistic behavior” against inmates. 20

“Back of the Yards” Campaign

The “Back of the Yards” was the name given to a primarily Polish immigrant neighborhood behind Chicago’s Union Stock Yards, where animals were butchered for meat-packers. At the time, meatpacking was the city’s second-largest industry after steel; Chicago’s meat-processing industry was the setting of socialist activist-author Upton Sinclair’s 1905 novel The Jungle. In 1938, Alinsky was assigned to profile poverty and crime in the neighborhood, which brought him into contact with the political activist Herb March. March was an organizer and public speaker for the Young Communist League, a radical labor group, and was associated with the Committee for Industrial Organization (later the Congress of Industrial Organizations), a federation of unions formed in 1935 by labor leader John L. Lewis and now part of the AFL-CIO. 21

Alinsky, who admired Lewis and union solidarity, sympathized with March’s efforts to organize Chicago’s packinghouse workers and simultaneously to form an anti-fascist labor front from the city’s disparate working-class ethnic and religious minorities. Their conflict with the packinghouse companies burst into violence in late 1938 and early 1939, with an assassination attempt on March’s life. 22

Their efforts at organizing the packinghouse workers and improve living conditions in the area led March and Alinsky to form the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council in 1939, Alinsky’s first venture into political activism. The Neighborhood Council drew heavily upon CIO members and local religious bodies, particularly Roman Catholic parishes with “progressive” clergy such as Chicago Bishop Bernard J. Sheil. Sheil, who described himself to friends as a “leftist.” 23

The Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) and Early Community Organizing

Also see Industrial Areas Foundation (Nonprofit)

The success of the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council led Alinsky to resign from the Institute for Juvenile Research in 1940 to pursue activism full-time. Bishop Sheil introduced him to Marshall Field III, an investment banker, heir to a local family department store fortune, and owner of the Chicago Sun-Times, as well as a liberal Republican interested in criminal justice reform. Field provided $15,000 to support Alinsky’s activism through the newly formed Industrial Areas Foundation created in early 1940, whose board Field soon joined. 24

The Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) received further support from Bishop Sheil, a board member, to pursue its mission of activating religious congregations in center-left political activism. Sheil later donated at least $10,000 to the IAF in 1948—the largest sum it had yet received—through the Catholic Youth Organization. Sheil later resigned from the boards of both organizations after conflict erupted with then-U.S. Sen. Joseph McCarthy (R-WI) over the bishop’s downplaying of the threat of Communism. Also on the group’s founding board was Kathryn Lewis, daughter of United Mine Workers president and CIO architect John L. Lewis, helping to cement Alinsky’s relationship with the latter and with the CIO. 25

Alinsky envisioned the IAF’s role as fostering “citizenship” among underrepresented groups of Americans (particularly immigrants), which he defined as “active rather than passive . . . participation” which “questioned authority, took the initiative to address community problems, and developed an understanding of how events and forces in the larger world affected one’s own life and community.” 26 From this was born the idea of “community organizing,” Alinsky’s vision of aligning disparate interest groups in a single coalition to achieve their common goals. As he put it: 27

“When I talked to the Mexicans, the main importance [was the] abolition of the discriminatory practices and unfair prejudices which the Mexicans had to endure. To the Catholic Church, [a community council] was presented as an organization which fundamentally concerned the strengthening of the Catholic Church; to the Protestant Church, the same; to ambitious individuals, a medium for that satisfaction of their own desires for personal aggrandizement; to the Negroes, an organization dedicated to the abolition of Jim Crow practices; to the union man, an organization that would develop the rights of organized labor.”

Alinsky’s age and poor eyesight meant that he was not drafted into the U.S. military during World War II. Nevertheless, he “saw himself very much as a participant in the struggle between good and evil that was being waged on the battlefield in Europe,” and although details are few he reportedly aided the War Manpower Commission to maintain worker morale in key defense industries. 28

After the end of the war in 1945, Alinsky sought funding from wealthy donors and philanthropists in New York and the Northeast. Beginning in 1945, the IAF’s $20,000 annual budget grew by an additional $5,000 annually from Agnes E. Meyer, the wife of financier and Washington Post publisher Eugene Meyer as well as a journalist and liberal civil rights advocate later active in the Lyndon B. Johnson administration. 29 (Meyer’s daughter, Katherine Graham, later led the Post’s coverage of the Watergate Investigation in 1973 leading to indictments and the resignation of President Richard Nixon in 1974.)

The Archdiocese of Chicago provided $118,800 to the IAF in 1957 to study the effects of changing demographics in the city, given the rapid northward migration of Black Americans and decline in the city’s middle-class white populations. Alinsky himself considered “racial integration an end in itself” and urged the Catholic Church to help secure it by using “racial quotas . . . which would allow for a limited number of blacks to move into white neighborhoods” (although he also called the word “quota” an “ugly word”). At the time, legal covenants prohibiting the sale of property to persons of a particular race were permissible. 30

Ultimately, the idea of quotas met with anger from local residents “as if somebody had pulled the pin of a grenade in a crowded room,” according to Alinsky’s biographer. Ironically, the decline of the Chicago meatpacking industry after World War II contributed to a rift in the 1950s between black and white workers, with the Back of the Yards neighborhood becoming “anti-black” and ethnically less integrated as a result, much to Alinsky’s embarrassment. The Back of the Yards Council launched an ad campaign entitled “Why Move Away?” meant to curb emigration from the neighborhood. 31

As of 2021, there are approximately 65 IAF affiliates across the United States, with international affiliates in Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, and Germany. 32 Of these, the vast majority are faith-based or “interfaith.” Because of the IAF’s particular influence among religious bodies, the organization has drawn criticism for hijacking Christian theology for political purposes. Investigative reporter Stephanie Block, an Alinsky critic, observes of this influence that “the most serious ramifications of Alinskyian community organizing are theological.”33

“The IAF’s influence is “liberationist.” Prayer and religious symbols are used for the IAF’s own organizational ends, and scripture frequently is “spun” to lend support to organizational actions. The IAF promotes a “political” ethics, namely that “the ends justify the means,” and teaches morality-by-consensus. These three characteristics of the IAF—repurposing religious elements for secular purposes, Machiavellian public actions, and moral relativism—are features of liberation theology, as well.”

Liberation theology is a movement developed within Roman Catholicism in the 20th century, particularly in Latin America, that uses civic activism and public policy campaigns against “sinful” government institutions to advance politically left-progressive income inequality, poverty, and other social issues. 34

In 1976, IAF board member Monsignor Jack Egan and a local Alinsky-style organization, the Campaign for Human Development, organized a three-day conference for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in Detroit, Michigan. The conference’s theme was “A Call to Action,” but due to the strong influence of IAF and other left-wing activists one conservative priest noted that its “true theme was a ‘Call to Revolution.’” The conference recommended a number of extensive changes to Roman Catholic religious doctrine, organization, and practice, including: 35

- Adopting a more “democratic” ecclesiastical hierarchy;

- Abandonment of doctrines concerning contraception, abortion, the right to private property, the right to reasonable profit, and support for national defense;

- Allowing communion for Catholics who eschewed church teaching about marriage;

- Ordination for women as priests and bishops;

- Marriage for priests; and

- Proclaiming socialism and pacifism as “doctrinally true and morally good practice”

Temporary Woodlawn Organization (TWO)

In 1961, the failure of his racial-integrationist housing quotas led Alinsky to reimagine his organizing campaigns around a new “black community organization” that could bargain collectively with the city of Chicago, government agencies, and private companies. He centered the campaign on Woodlawn, a predominantly lower-class black neighborhood, and accordingly named the organization the Temporary Woodlawn Organization (TWO). Alinsky described the organization to a friend: “There is no substitute for organized power . . . We also know that there is no Negro organization in the field equipped or able to do the kind of job that has to be done.” In a memorandum on the campaign, he added, “We are fed up with the moving out of low-income and, almost without exception, Negro groups and dumping them into other slums, building houses for the middle-income groups, and all of this in the name of urban renewal.” 36

TWO’s support largely came from black Chicagoans and those on the radical left, particularly since the former increasingly made up most of the population in new poor neighborhoods formed by the outflux of white families to the city’s suburbs. According to Alinsky’s biographer, TWO failed to win over any significant bloc of white supporters in part because Chicago did not require municipal employees to live in the city limits. 37

Alinsky and his employees began by systematically dividing up Woodlawn into sections that each organizer walked, speaking with residents about their problems and listening to complaints. From these he organized public protests, including the “Square Deal” campaign which included some 600 residents in a march to protest local businesses suspected of fixing scales and refusing to negotiate with the TWO. 38

Voter Registration Campaigns

The Industrial Areas Foundation extended its reach to California in 1947. Fred Ross, an activist interested in organizing Mexican-Americans and voter registration drives, was hired by IAF and soon founded an informal “sister” organization, the Community Service Organization (CSO). Between 1947 and 1949 the CSO became a “hub” for voter registration efforts in preparation for the 1949 Los Angeles City Council election, hiring 125 deputy registrars. Ross, who was paid by the IAF, took great pains not to jeopardize the IAF’s tax-exempt status by labeling the drive “nonpartisan”; in reality, the group’s goal was to elect Democrat Edward Roybal, who won the seat and later won election to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1962. 39

In 1950, Alinsky expanded his efforts to organizing as many as 16 million people nationwide, both to form voter registration campaigns as well as People’s Organizations. To fund this ambitious operation he applied for a grant from the Ford Foundation, which was denied, and to the Ford Foundation spin-off Fund for the Republic, based in California, which fell through. Eventually he secured funding from the Schwarzhaupt Foundation, the philanthropy of the late whiskey magnate Emil Schwarzhaupt, who made his fortune selling alcohol after Prohibition was repealed from liquor stockpiled prior to its passage in 1919. 40

Accusations of voter fraud in Cook County, Illinois (centered on Chicago), in 1960 caused the state to wipe clean its voter file. Alinsky’s Temporary Woodlawn Organization organized a mass voter registration drive focused on Chicago’s Black population which Alinsky’s biographer later described as “the largest single voter-registration event ever at City Hall.” Woodlawn delivered 17,000 votes for Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy, who won Illinois by 8,858 votes. 42

“And you, Alinsky! When that great day of America, election day, comes around—that day of the right to vote for which our ancestors fought and died—when that great day comes around you care so little for your country that you never even bother to vote more than once!”

Rochester, FIGHT, and the Birth of Shareholder Activism

Beginning in early 1965, Alinsky moved his organizing operations to Rochester, New York, aiming to dismantle the city’s “white power structure” (“the enemy”) and disparaging Black living conditions as a “little Condo”: 43

“Rochester probably more than any Northern city reeks of antiquated paternalism. It is like a Southern plantation transported to the North. Negro conditions in Rochester are an insult to the whole idea of the American way of life. I have seen in Rochester people who are sick to death of being treated like chattel, who find themselves regarded as a necessary evil.”

At the time, Rochester’s previously small black population had recently experienced a surge in population (particularly in impoverished neighborhoods), unemployment, and violent riots amidst general unrest nationwide in the early 1960s. While Rochester historically was affluent and free from political corruption, it relied heavily on private philanthropy to fund social welfare causes, not government funding. The vast majority of blacks who had recently moved to the city from outside of New York state were unskilled laborers and faced high unemployment rates, and overwhelmed the city’s welfare system. Alinsky, who had followed recent unrest in the city, blamed riots in Rochester and across the United States on “white racism.” He remarked in November 1964: 44

“There’s a tactic I’ve always wanted to try, and Rochester would be the perfect place. You buy blacks three or four hundred tickets to the Rochester symphony. But before the performance, they’ll all get together for dinner, except this won’t be an ordinary dinner, it’ll be a baked-bean dinner. Then they’ll go to the symphony and far it out of existence. How would that go over in Rochester? Wouldn’t people love that?”

Alinsky—in a 1965 meeting held with the Rochester Area of Churches, a local social welfare group—suggested the organization be called “FIGHT” in order to “play on the whites’ fears,” building the acronym backwards to form “Freedom, Integration, God, Honor, Today.” Funding for FIGHT came from a slew of mainline Protestant denominations and the Catholic church. 45

The group’s first executive director and president, Franklin Florence, was a far-left black pastor at a local Church of Christ interested in advancing “black power.” Alinsky reportedly liked him for his “aggressiveness.” Florence was close friends with the radical black Muslim leader Malcolm X, a guest at Florence’s house shortly before he was murdered in February 1965. Florence had previously participated in the civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 1963 protests in Selma, Alabama, and had organized a sit-in in at the Rochester police headquarters to protest alleged police brutality against black Muslims. Florence was opposed to white leadership of FIGHT, explicitly identifying it as a black organization, leading Alinsky’s allies to form the white-led group Friends of FIGHT (later Metro-Act) to “keep liberal whites from becoming awkward, disenchanted bystanders.” 46

FIGHT included a major voter registration component, branded “Register for Power,” but was surprisingly critical of federal welfare programs for Rochester instituted by President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, considering the effort “welfare colonialism.” In its place Alinsky wanted specially trained, federally funded local representatives to organize “community sources of power” through “mass meetings” to develop poverty programs as local residents, not bureaucrats or politicians, saw fit. 47

In 1966, FIGHT launched a campaign against Kodak, a staple employer headquartered in Rochester, pressuring the company to hire 1,500 “unemployed blacks with limited skills and little work experience” whom FIGHT agreed to coach so they could hold down their jobs. (Alinsky accused the camera company of “run[ning] the town of Rochester like a Southern plantation.”) That was followed by a campaign to push Kodak into sponsoring a larger jobs program which emphasized minority employment, using FIGHT as the “exclusive referral agency” for trainees. Negotiations ultimately fell through, prompting Florence to blame the failure on white clergymen and the country’s white leaders and scream at one allied activist: “You whites always lie!” He then sent a telegram release to the media haranguing Kodak: 48

“Please be advised that the Negro poor of Rochester and the poor throughout the country from Harlem to Watts are not satisfied with your “See No Evil” and “Hear No Evil” attitude. Institutional racism as exemplified at Kodak is amoral und un-Christian. The cold of February will give way to the warm of spring and eventually to the long hot summer. What happens in Rochester in the summer of ’67 is at the doorstep of Eastman Kodak.”

Alinsky used his powerful sway with mainline Protestant denominations, whose members made up the bulk of FIGHT’s white allies, to threaten to withhold their proxies’ votes during Kodak’s upcoming shareholders’ meeting with the board of directors — amounting to some 40,000 shares in the company out of 80 million — until company leadership surrendered to FIGHT’s demands. This was the first instance of shareholder activism in support of a “social justice” cause, today a commonplace practice of left-progressive activism. Florence threatened the company on the third anniversary of Rochester’s race riot, saying, “You will honor the agreement or reap the harvest” and later adding, “This is war.” Alinsky, sensing that Florence’s threatening and extreme language was turning public (and ecclesiastical) support in Kodak’s favor, announced to the press gathered outside the shareholders’ meeting: 49

“We are ready to move on a national scale and FIGHT is going to be the fountainhead for the resurrection of the civil rights movement. . . . We’re going to ask the churches to put their stocks where their sermons are.”

National publications including Fortune and The Wall Street Journal, however, attributed the dispute less to “corporate racism or malevolence” than “inept negotiating.” They pointed out that Kodak had recently joined a corporate-led hiring group called Rochester Jobs, Inc., that promised to hire 1,500 local unemployed blacks. FIGHT’s allied churches also walked back their threats to withhold votes. Alinsky’s biographer writes, “In short, quite a few church officials apparently felt that a full-throttle campaign against Kodak was out of proportion to the corporation’s current sins.” After fitful negotiations facilitated by liberal civil rights activist and future U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-NY), Kodak and FIGHT agreed to a vague joint effort to “recruit and counsel Rochester’s black unemployed in June 1967, ending the campaign. By Spring 1968, an embattled and disappointed Alinsky withdrew the Industrial Areas Foundation from Rochester, the last black ghetto he would organize. 50

Training Future Activists

The remainder of Alinsky’s life and career was focused on training younger political activists through the Industrial Areas Foundation. Beginning in 1969, he planned to have 40 full-time students who would undergo 12-15 months of intensive training paid for by the student’s sponsoring organization. Alinsky grilled students with the initial question, “Why do you want to organize, goddammit?” with the correct answer being “power.” Students studied the tactics of labor leader John L. Lewis and Louisiana Gov. and populist leader Huey “Kingfish” Long (D), as well as The Federalist Papers, satirist H. L. Mencken, Mark Twain, theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, and Thucydides’ account of the dialogue between the Athenians and Melians in the Peloponnesian War. Alinsky’s students worked extensively in the field, beginning with an anti-smog campaign in Chicago, birthing the Campaign Against Pollution (later Citizens Action Program) in summer 1969. 51

Political Beliefs

Throughout Alinsky’s academic and criminology career he had little involvement in political causes. That began to change in the mid-1930s with the advent of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation to combat the Great Depression, developments in labor activism, and changes in Soviet foreign policy.

Views of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany

The American Left prior to World War II was split in its attitudes towards American foreign policy concerning the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. The Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) resulted from a 1921 merger of two American Communist parties at the order of the Communist International (Comintern), a faction set up by the Soviet Union to encourage Communist uprisings in foreign countries. 52

CPUSA initially supported the long-term goal of violently overthrowing the U.S. government and instituting a pro-Soviet socialist regime in its place. That changed in 1935, when the Soviets dropped their opposition to President Roosevelt’s New Deal, signaling to its CPUSA puppet that it should follow suit. These changes came as a result from a Soviet foreign policy blitz meant to shift its attention away from Western capitalist countries and unite anti-fascist forces against the threat from Nazi Germany and other powers aligned against Communism. 53

This also had the effect of uniting pro-Soviet Communists in the United States with the broader non-Communist Left — Alinsky among them — which opposed Adolf Hitler’s regime but were not necessarily socialists. This broader Left began to view the Soviet Union as key to defeating fascism. An Alinsky biographer describes his newfound political awareness: 54

“The united-front strategy would have appealed to Saul Alinsky on several levels. First, it gave a high priority to stopping Hitler, whom, Alinsky said, he “hated with a passion.” Second, it included a measure of political realism . . . by placing pragmatism over ideological concerns, to build a new political coalition.”

“Although Alinsky had not been enthusiastic about some of Roosevelt’s politics . . . and though he criticized the early New Deal for not being fully committed to sweeping, fundamental change . . . it was simply more important to stop Hitler and the forces of fascism than to dwell on Roosevelt’s shortcomings.”

Alinsky volunteered to raise money to aid the International Brigades, Comintern-backed paramilitary forces that fought against the army of fascist General Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Alinsky reportedly “liked what the Stalinists were doing in Spain,” according to the liberal Chicago politician Leon Despres. Despres said of Alinsky that “I don’t think he ever remotely thought of joining the Communist Party [but] emotionally he aligned very strongly with it.” 55 He also considered the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council he founded in Chicago “an answer to the forces of reaction at home and abroad,” a “defense against right-wing hatemongers and the forces of fascism.” In the early Cold War years, Alinsky told friends that he believed “’certain Fascist mentalities’ posed a far greater threat to the country than ‘the damn nuisance of Communism,’” in part because he did not believe that Americans would “follow communist exhortations like sheep.” 56

By the early 1960s, however, Alinsky had largely abandoned the united front strategy. Alinsky’s biographer, Sanford D. Horowitz, notes that Alinsky was “disgusted by the professional Red baiters” and left-wing union “purges” common in the era, and particularly with Sen. Joseph McCarthy (R-WI) and the U.S. House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA). 57

According to Horowitz, “Alinsky was more radical in his inclinations, convictions, rhetoric, and wishes than in his actions, which took a more pragmatic form. [But] he was never a member of the party or a communist.” 58 He maintained close proximity to numerous active or accused Communists, including United Packinghouse Workers president Ralph Helstein (who would lead the Industrial Areas Foundation after Alinsky’s death), who was accused of Communist sympathies by the HUAC in part because he allowed Communists in union leadership positions. Still, he “had little patience and sympathy for the relatively few communists” he encountered in his community organizing efforts and considered them “quarrelsome, rigid, dour, [and] humorless.” 59

Alinsky’s 1971 book Rules for Radicals attempts to separate his idea of “revolution” from communism, with the former far exceeding in scope the latter. He wrote, “This is a major reason for my attempt to provide a revolutionary handbook not cast in a communist or capitalist mold, but as a manual for the Have-Nots of the world . . . to get [power] and to use it.” To that end, the book praises Soviet revolutionary Vladimir Lenin, not for his political beliefs, but for being a model “pragmatist” for impractical and extreme American leftists of the 1970s: 60

“Power comes out of the barrel of a gun!” is an absurd rallying cry when the other side has all the guns . . . when [Lenin] returned from Petrograd [St. Petersburg] from exile, he said that the Bolsheviks stood for getting power through the ballot but would reconsider after they got the guns! Militant mouthings? Spouting quotes from Mao, Castro, and Cheo Guevara, which are as germane to our highly technological, computerized, cybernetic, nuclear-powered, mass media society as a stagecoach of a jet runway at Kennedy airport?”

However, the book also offers criticism of the repression and lack of free speech allowed by the Soviet Union and other communist governments: 61

“Let us in the name of radical pragmatism not forget that in our system with all its repressions we can still speak out and denounce the administration, attack its policies, work to build an opposition political base. True, there is government harassment, but there is still that relative freedom to fight. I can attack my government, try to organize to change it. That’s more than I can do in Moscow, Peking, or Havana. Remember the reaction of the Red Guard to the “cultural revolution” and the fate of the Chinese college students. Just a few of the violent episodes of bombings or a courtroom shootout that we have experienced here would have resulted in a sweeping purge and mass executions in Russia, China, or Cuba.”

In 1941, an FBI investigation brought on by his community organizing efforts with the Industrial Areas Foundation concluded that “Alinsky was not a communist” nor had he “ever made any remarks or exhibited any acts against the United States Government, or in favor of any foreign government.” He was never called to testify before Congress in its investigations into Communist organizations and activists, although the FBI monitored many of his activities in the aftermath of World War II. 62

Reveille for Radicals

Alinsky’s first book, Reveille for Radicals (1946), was an attempt to define “radicalism” while criticizing the American liberalism he observed in the immediate aftermath of World War II and throughout the remainder of his life. “Liberals like people with their head,” Alinsky wrote, while “radicals like people with both their head and their heart.” Later in the mid-1960s (and height of the civil rights movement), he boasted that what distinguished him from liberals and even top civil rights leaders was that “I do not in any way glorify the poor.” He was critical of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society and its War on Poverty, considering it doomed to fail because liberalism was simply insufficient for accomplishing the sweeping change he envisioned: 63

“I don’t want to minimize their [liberals’] function . . . I think the agitation of the white liberals through the years prepared the climate for the reformation which you have to have before you can have a [civil rights] revolution . . . The trouble with my liberal friends is that their moral indignation and sense of commitment vary inversely with their distance from the scene of conflict.”

In Reveille for Radicals, Alinsky laid out his vision of a country which “placed human rights above property laws,” abolished the “present caste system” created by inherited wealth, weakened local power in favor of federal authority, and funded universal public education. According to his biographer, Sanford Horwitt, Alinsky sought a third way between European Marxism and laissez-faire capitalism but was less interested in defining an alternate form of government to fit it. 64

Alinsky was also critical of the “conservative” direction Big Labor had taken in the early 1940s, when the more moderate and anti-communist American Federation of Labor (AFL) began to outcompete the increasingly far-left Congress of International Organizations (CIO), which had broken with Franklin Roosevelt in the 1940 presidential election under John L. Lewis’s leadership. He wrote: 65

“The organized labor movement as it is constituted today is as much of a concomitant of a capitalist economy as capital . . . [But radicals] want to advance from the jungle of laissez-faire capitalism to a world . . . where the means of economic production will be owned by all of the people instead of just a comparative handful.”

Later Alinsky clarified what he meant by “private ownership of [the] means of production” in a letter to Valentine Everit Macy, a New York industrialist and early Industrial Areas Foundation donor: “What I was really driving at was not kicking up Hell on what would be the best kind of economic organization . . . I did not mean there that I am opposed to private ownership, but I believe that there are certain major services that are basic to the American public which could stand considerable modification and possible public ownership in the sense of the Postal Service.” Alinsky biographer Sanford Horwitt, in his examination of the Alinsky-Macy correspondence, writes that “it is doubtful that their brief exchange here had much effect on Alinsky’s thinking about economic theory, which he was not very much interested in . . . Before the end of [World War II], economists and other intellectuals could talk seriously about the possible end of capitalism. Now, after the war, even those who were critical of capitalism seemed to accept it . . . not as an ideal but as a fact.” 66

In the place of traditional labor unions he proposed a nationwide network of “People’s Organizations” focused less strictly on higher pay and better working conditions and more broadly on the “fundamental problems of America’s social problems”—“united to conquer all of those destructive forces which harass the workingman and his family.” 67 People’s Organizations formed the basis of Alinsky’s theory of community organizing and were to be networks (“an organization of organizations”) founded by neutral outsiders but characterized by the “centrality of native or indigenous leadership” and an emphasis on “collective action, cooperation, and unity.” 68

Reveille for Radicals met with mixed reception from readers on the Left. The New York Times, New York Herald Tribune, and Time praised Reveille for Radicals. But The New Republic, The Nation, and Commentary — at the time, all left-wing or socialist magazines — criticized the book as insufficiently harsh towards capitalism and even uncomfortably close to fascism, which similarly espoused a “radical third way” between socialism and democratic capitalism. 69

“Black Power” Movement

Alinsky signaled his support for the term “black power” at the height of the violence and extremism of the late civil rights era in the 1960s as an extension of his general views of political power dynamics: “I agree with the concept. We’ve always called it community power, and if the community is black, it’s black power,” he said in 1966. He explained the negative reaction among many American whites to “black power” by suggesting that black is “the color of evil” while power “suggested coercion, even corruption.” But he also cautioned radical black leaders to “stop going around yelling ‘Black Power!’ and just addressing meetings” because “it’s time they got trained to really go down and organize.” 70

Alinsky maintained friendly relations with members of the black nationalist movement, including the far-left and racist leader Franklin Florence in Rochester, New York, and Stokely Carmichael (later named Kwame Ture), a socialist and separatist who abandoned Martin Luther King, Jr.’s nonviolent resistance in favor of violent revolution. Carmichael, asked to cite a concrete example of “black power,” identified Alinsky’s activism with FIGHT in Rochester. 71

By the late 1960s, Alinsky dropped his efforts at organizing black ghettos amidst growing attacks from far-left black activists. In 1971, he announced that “all whites should get out of the black ghettos. It’s a stage we have to go through.” In 1968, for example, he was listed among one extremist’s six categories of “exploiting liberals” as an “economic exploiter” because his Industrial Areas Foundation charged fees for Alinsky’s services (other “exploiters” included Abraham Lincoln and the recently murdered Sen. Robert F. Kennedy (D-NY)). In response, Alinsky wrote to a friend that he found the statement “Repugnant and nauseous . . . I and my staff associates not only plead guilty to supporting America, but we will go further and gladly admit that we love our country.” 72

Politics of Religion and Philosophy

Alinsky’s interest in religious organizations, particularly the Roman Catholic Church, “centered largely on its politics,” not its “rituals and dogma,” of which he could be “openly contemptuous.” “I detest and fear dogma,” he wrote in Rules for Radicals (1971), because “dogma is the enemy of human freedom.” 73

He had a somewhat greater interest in theological and philosophical issues, but principally Alinsky was concerned about implementing “democratic values” and the “ideals of social and economic justice [which] ought to central concerns of the Catholic Church.” That extended to Judaism (Alinsky was Jewish) as well; a Jewish couple friendly to the Alinskys recalled one Seder dinner: 74

“We tried to start the Seder service [with] Saul taking an active part. He knew Hebrew and could read from the Haggadah. It wasn’t very long, however, before it got to be an absolutely panic because he just hammed it up so . . . and at the same time sort of poked fun [at the whole thing]. [It] turned out to be a real fiasco in terms of anything serious, but it was a fun evening eventually.”

Much of Alinsky’s community organizing targeted Christian denominations. In Chicago, that was largely the Roman Catholic Church, which provided numerous left-leaning clergymen sympathetic to Alinsky’s calls for social reform to combat extreme poverty and poor living and working conditions. In the mid-1960s, he observed that, “Without the ministers, priests, rabbis, and nuns, I wonder who would have been in the Selma [civil rights] march.” Of Catholicism, he said: 75

“The teachings of Christ and the philosophy represented by him . . . [is] one of the most revolutionary doctrines the world has ever witnessed, a doctrine so radical that both by itself as well as in its implications it would make the most left-wing aspect of communism appear conservative. This radical, revolutionary philosophy of Catholicism makes it impossible for one to subscribe to it and yet be a centrist or a right-wing conservative. [Those who have] may be Catholics in name, but they are pagan in soul.”

Gretta Palmer, a journalist and Catholic convert, later recalled a discussion with Alinsky in which he agreed with her premise that the “sanctity of the individual was only possible within a religious framework.” Alinsky retorted: 76

“[Your] statement cannot stand completely by itself as for example, take the Nazis. I hate dictatorship, totalitarianism and Fascism with all of my heart and soul . . . I would have been in favor of wholesale execution of the Nazis and, sister, I mean wholesale. Yet I suppose a Nazi is a child of God. But on this point of the conflict between the basic love for all individuals which is fundamental to organized religion, as over against the expression of hate which I have just given vent to, there seems to be [a] fundamental contradiction . . . I hate injustice; I hate persecution; I hate people that for their own personal reasons degrade great parts of humanity; I hate them with a burning passion and yet they are individuals and I firmly believe in the concept of the dignity and sanctity of the individual.”

Rules for Radicals

Background

Alinsky published his second and final book in 1971, originally titled The Morality of Power, then Rules for Revolution, and finally Rules for Radicals: A Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Radicals. Like his first book, Reveille for Radicals (1946), it was generally applauded by liberals and criticized by leftists, particularly those on the New Left. 77 Alinsky described its purpose as follows: “The Prince was written by Machiavelli for the Haves on how to hold power. Rules for Radicals is written for the Have-Nots on how to take it away.” 78

Theory of Power and Community Organizing

In the book, Alinsky lays out the great problems of the contemporary United States as he and other men of the ideological left saw them: Materialism, the ultimate vice and draw of the American middle class, spurred to unprecedented levels with the prosperity achieved after World War II; rampant feelings of meaninglessness, leading to sluggish relationships and poor individual health; and an almost unfathomable complexity to modern life, technology, and social dynamics unknown to prior generations. “There is a feeling of death hanging over the nation,” he wrote. “When they [the youth] talk of values they’re asking for a reason. They are searching for an answer, at least for a time, to man’s greatest question, ‘Why am I here?’” 79

Alinsky argued that these factors robbed the youth of any sense of moral clarity previously achieved through religion, science, and philosophies, replacing it with “hopelessness and despair” leading to “morbidity.” The outcome of these factors was to destroy pluralism — participation in American democracy — through indifference, which, considering Alinsky defined “power” as participation, effectively fueled widespread powerlessness and enabled the “Haves” to dominate the “Have-Nots.” 80

“The democratic ideal springs from the ideas of liberty, equality, majority rule through free elections, protection of the rights of minorities, and freedom to subscribe to multiple loyalties in matters of religion, economics, and politics rather than to a total loyalty to the state . . . People cannot be free unless they are willing to sacrifice some of their interested to guarantee the freedom of others. The price of democracy is the ongoing pursuit of the common good by all of the people.”

Alinsky wrote that “reformation” — which he defined as public “disillusionment” with the status quo — must precede “revolution,” which did not necessarily include violence but always meant thorough, systemic change. He considered Christianity, for example, a revolution and the advent of capitalism a reformation. “History is a relay of revelations,” he wrote, “carried by the revolutionary group until this group becomes an establishment,” at which point the next revolutionary group continues the process. 81

He praised power as “the dynamo of life,” self-interest as the real force behind false “altruism and selflessness,” compromise as the basic definition of “a free and open society,” ego (as opposed to egotism) as an essential respect for one’s own dignity, and conflict or controversy as a “harmony of dissonance” within a democratic society. 82

Central to his thesis is the idea of “radical pragmatism,” which he stacked against ideology, arguing that an ideology’s “basic truth” feeds all of its conclusions. But to an activist, truth is always “relative and changing” because the social conditions he desires to solve are ever-evolving. Consistency in politics, in fact, was not a virtue to Alinsky: “Men must change with the times or die.” The effective organizer must be reflective and free from illusion. “As an organizer, I start from where the world is, as it is, not as I would like it to be . . . That means working in the system,” he warned his fellow left-wing activists. Alinsky warned that ineffective tactics threatened to alienate the country’s middle- and lower-middle class. Instead of attention-seeking through antics and shock value, radicals must be “resilient,” “fluid,” and “sensitive” to changing conditions in order to maintain even a “degree of control over the flow of events.” 83

The Ideal Community Organizer

Alinsky defined a community organizer as an operative who “lives, dreams, eats, breathes, [and] sleeps one thing”—building a “mass power base” for a given community. Since, Alinsky reasoned, most people don’t know what they want or need, an organizer’s first job is to discover and agitate people around that, then build “confidence and hope in the idea of organization” with limited victories before seeking out bigger targets, thus building the “power to compel negotiation” with more powerful opponents. Alinsky’s idea of local community-based organizations (what he earlier termed “People’s Organizations”) are necessarily multi-issue in scope in order to pull in enough supporters to establish broad appeal. He contrasted them with labor unions, which have “specific economic issues” and therefore narrow appeal. 84

Alinsky’s ideal community organizer would be curious, irreverent towards “dogma” and “finite” definitions of morality by “challenging, insulting, agitating, discrediting” it, imaginative, and naturally well-organized even in a disorganized situation while possessing a sense of humor. He believed that labor union organizers made “poor community organizers” because they were too fixated on “particular contract dates” related to wages, working conditions, and vacations, and lacked flexibility. Above all, Alinsky argued that a good community organizer must possess strong communication and persuasion skills, either to pick out common points of experience with others or even to create them using stories and illustrations meant to elicit emotional responses. 85

“For example, I have always believed that birth control and abortion are personal rights to be exercised by the individual. [But] if, in my early days when I organized the Back of the Yards neighborhood in Chicago, which was 95 percent Roman Catholic, I had tried to communicate this . . . that would have been the end of my relationship with the community. That instant I would have been stamped as an enemy of the church and all communication would have ceased.”

Recommended Tactics

In the book’s prologue, Alinsky identifies his intention not to offer “unsolicited advice,” but the “experience and counsel that so many young people have questioned me about through all-night sessions on hundreds of campuses in America.” He is careful to show that his aim is genuine change, not merely action or word. “This failure of many of our younger activists to understand the art of communication has been disastrous,” he wrote. 86

“First, there are no rules for revolution any more than there are rules for love or rules for happiness, but there are rules for radicals who want to change their world; there are certain central concepts of action in human politics that operate regardless of the scene or the time. To know these is basic to a pragmatic attack on the system. These rules make the difference between being a realistic radical and being a rhetorical one who uses the tired old words and slogans, calls the police “pig” or “white fascist racist” or “motherfuckers” and has so stereotyped himself that others react by saying, “Oh, he’s one of those,” and then promptly turn off.”

. . .

“Effective organization is thwarted by the desire for instance and dramatic change . . . The present generation wants to go right into . . . confrontation for confrontation’s sake—a flare-up and back to darkness. To build a powerful organization takes time. It’s tedious, but that’s the way the game’s played . . .”

In general, a radical’s tactics may include nonviolent or violent measures; Alinsky wrote that the choice depended upon who the radical’s opponents are. Members of the anti-Nazi resistance in World War II, for instance, necessarily adopted “assassination, terror, property destruction,” and other extreme tactics, and were consequently regarded “as a secret army of selfless, patriotic idealists” to their friends and “lawless terrorists” to their enemies. The morality of these actions is relative. He considered it a “rule” that in politics as in war, “the end justifies almost any means,” and added that “you do what you can with what you have and clothe it with moral garments.” Even Mahatma Gandhi was nonviolent because he “did not have the guns” or the “the people to use the guns.” 87

More specific to American community organizers, Alinsky stressed the importance of both real power and perceived power. He advised using jail time as a means of forcing revolutionary sentiment so long as the sentence was “relatively brief, from one day to two months.” He taught organizers to never leave the limits of their own supporters’ experience, but to force one’s opponents outside of their limits. He encouraged ridicule as “man’s most potent weapon,” threats as “usually more terrifying than” the action threatened, and instructed organizers to “pick the[ir] target, freeze it, personalize it, and polarize it.” He added: “Make them live up to their own book of rules. You can kill them with this, for they can no more obey their own rules than the Christian church can live up to Christianity.” 88

“[S]ince the Haves publicly pose as the custodians of responsibility, morality, law, and justice . . . they can be constantly pushed to live up to their own book of morality and regulations. No organization, including organized religion, can live up to the letter of its own book. You can club them to death with their “book” of rules and regulations.”

Alinsky’s biographer observes that Alinsky viewed his book as a historic successor to the works of Thomas Paine, Alexis de Tocqueville, Samuel Adams, Vladimir Lenin, and other “radicals,” and intended it to critique the post-war accumulation of power by the American middle class, his main target for the remainder of his life. 89 He encouraged young activists with middle class backgrounds to stop rejecting it, and instead organize it: 90

“With rare exceptions, our activists and radicals are products of and rebels against our middle-class society. . . Our rebels have contemptuously rejected the values and way of life of the middle class. They have stigmatized it as materialistic, decadent, bourgeois, degenerate, imperialistic, war-mongering, brutalized, and corrupt. They are right; but we must begin from where we are if we are to build power for change . . . [the activist] should realize the priceless value of his middle-class experience . . . [as] invaluable for organization of his “own people.””

“The middle classes are numb, bewildered, scared into silence,” he concluded.” They don’t know what, if anything, they can do. This is the job for today’s radical—to fan the embers of hopeless into a flame to fight.” 91

Views of Power

Alinsky had first framed his vision of community organizing in his 1946 book Reveille for Radicals, in which he described organizers as leading the “war against the social menaces of mankind” by creating a society in which “victimized people could experience and express their self-worth, power, and dignity.” 92 He later expanded his concept of power as a moral good in Rules for Radicals (1971): 93

“The word power is associated with conflict; it is unacceptable in our present Madison Avenue deodorized hygiene, where controversy is blasphemous, and the value is being liked and not offending others. Power, in our minds, has become almost synonymous with corruption and immortality.”

“. . . Power is the very essence, the dynamo of life. It is the power of the heart pumping blood and sustaining life in the body . . . Power is an essential life force always in operation, either changing the world or opposing change . . . It is impossible to conceive of a world devoid of power; the only choice of concepts is between organized and unorganized power.”

He insisted that “power—not reason—was fundamental to the achievement of social change.” Although usually framed as an intellectual, he often employed an “anti-intellectual pose” and “uncivil” tactics to press a political advantage in contrast to many of his contemporary liberal social critics and commentators. Alinsky’s biographer notes that he considered power “amoral,” defining it as “the ability to act” while equating American democracy itself with “power relationships and struggles among competing groups and factions.” That democracy functioned best, he argued, when power was distributed evenly; but there is “no painless, polite way to change power inequities.” Alinsky’s biographer characterized the view as “Change means movement; movement means friction; friction means heat; and heat means controversy.” 94

Later in his life, Alinsky taught activists a “trinity of conflict, organization, and power” which formed the centerpieces of community organizing. He shaped his appeals to Christians and Jews in pseudo-Biblical terms, calling Moses “a great organizer” who “never [lost] his cool as a lesser man might have done when God” commanded him to lead the Israelites out of Egypt. Fundamentally, he believed, no one operates “outside of his self-interest,” so arousing people “who are demoralized and apathetic” requires one “agitate [them] to the point of conflict” and “fan” or “rub raw [their] resentments.” He once responded to a question about whether he believed in “reconciliation” saying, “Sure I do. When our side gets the power and the other side gets reconciled to it, then we’ll have reconciliation.” 95

Alinsky did not necessarily support violent measures; he noted that “Bull Connor with his police dogs and fire hoses down in Birmingham […] did more to advance civil rights than the civil rights fighters themselves.” Warned that police in Rochester, New York, had received riot training following violent unrest in 1964-1965, Alinsky remarked of his planned protests: “I believe in nonviolence, but I’m not Mahatma Gandhi. I believe in self-defense.” 96

Beginning in the mid-1960s, he began to advocate that imprisonment for civil disobedience should be a virtual prerequisite for leadership in activist organizations: 97

Imprisonment not only results in the development of [more effective] revolutionaries who have a complete strategy worked out as a result of their temporary withdrawal, but another consequence is the creation of martyrs—Gandhi’s hunger strike, the emergence of Martin Luther King because of his being put in jail . . . jailings [not only] become badges of honor but they also become credentials and a license for leadership.

Case Studies

Ku Klux Klan Costumes Incident

Alinsky’s biographer illustrates Alinsky-style tactics with an anecdote from 1972, shortly before his death. Students at Tulane University, Louisiana, asked Alinsky for advice in planning a Vietnam War protest against then-U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations George H.W. Bush. Alinsky dismissed the students’ plans to picket or disrupt Bush’s address; instead, he advised them to attend the speech dressed as members of the Ku Klux Klan, and” 98

…” whenever Bush said something in defense of the Vietnam War, they should cheer and wave placards reading “The KKK Supports Bush.” And that is what the students did, with very successful, attention-getting results.”

Bork Nomination

David Brock, now a Democratic political operative, noted the use of Alinskyite tactics in the campaign to halt the confirmation of judge Robert Bork to the U.S. Supreme Court when Brock was then a right-leaning journalist: “Bork’s opponents ran a slick campaign of distortion and innuendo, falsely presenting him as an advocate of back-alley abortions and mass sterilization to control pregnancies among female workers. This tactic of using public harassment and personal vilification was advocated by Saul Alinsky and the New Left as a means of defeating political opponents and seizing control of power.” 99

Clashes with the New Left

Alinsky’s biographer observes that, despite his vast role in shaping political organizing tactics in from the 1930s to the late 1960s, Alinsky “was not a hero or role model to all student activists. He had virtually no influence on the most important leaders of the New Left” of the 1970s, who were too politically extreme for him and wholly rejected the Democratic Party’s old New Deal coalition of the 1930s. Those groups included Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a radical split-off from the anti-communist socialist League for Industrial Democracy that eventually splintered into Maoist and non-Maoist factions in 1969. 100

SDS—whose leaders included Tom Hayden, Todd Gitlin, Paul Booth, and Lee Webb—is credited for spearheading what become the New Left. 101

“The early New Left emphasized the problems of apathy, indifference, and powerlessness, themes Alinsky had been expounding for twenty-five years . . . [however] these New Left leaders were not content with the goal of merely enabling the outsiders to become insiders; they wanted a different quality to the inside. While Alinsky himself was a harsh critic of [middle-class materialistic society], he was also adamant that effective organizing had to begin with “the world as it is” — and in the here and now, he told the young radicals sarcastically, what the poor want is a share of the so-called decadent, bourgeois, middle-class life that the SDS kids were so eager to reject.”

His biographer notes that Alinsky was present for Chicago’s infamous 1968 race riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. but was “clearly an outside during the demonstrations.” The violence and unrest extended to the Democratic Party’s 1968 convention in Chicago, culminating in a mass march-turned-riot on the day that Vice President Hubert Humphrey was to be nominated as the party’s presidential candidate in the coming election. Alinsky, who was “sympathetic to a point,” nevertheless urged the rioting students to “go back home and begin organizing so that next time they would be inside the convention hall wielding the power” instead of on the street. He also criticized the movement, saying, “They [protesters] aren’t interested in changing society. Not yet. They’re concerned with doing their own thing, finding themselves. They want revelation, not revolution.” 102

In Rules for Radicals, Alinsky observed: 103

“Today’s generation is desperately trying to make some sense out of their lives and out of the world. Most of them are products of the middle class. They have rejected their materialistic backgrounds, the goal of a well-paid job, suburban home, automobile, country club membership, first-class travel, security, and everything that meant success to their parents. They have had it. They watched it lead their parents to tranquilizers, alcohol, long-term-endurance marriages, or divorces, high blood pressure, ulcers, frustration, and the disillusionment of “the good life.””

But Alinsky believed that the outgrowth of extremism and violence from the civil rights movement followed by the radical youth movement of the late 1960s meant that the country’s lower-middle class was being won over by the conservatives and the Republican Party. The New Left’s extreme tactics and failure to communicate “within the experience of [their] audience” — including “attacks on the American flag” — were basically worthless for achieving real policy change. “They must be worked with as one would work with any other part of our population,” he wrote, “with respect, understanding, and sympathy.” 104 105

Influence on Other Political Figures

Cesar Chavez

For more information, see Cesar Chavez Foundation (Nonprofit)

Cesar Chavez, an influential labor leader known for organizing the National Farm Workers Association (later the United Farm Workers), began his activist career in 1952 as an employee of Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation, applying the latter’s tactics among agricultural laborers.. Later critics of Chavez’s political activism pointed to his close association with Alinsky as proof that he was sympathetic to communism, or even a communist himself, and suggested that Alinsky was a “behind-the-scenes mastermind” of the United Farm Workers. 106

Hillary Rodham Clinton

See also Hillary Clinton

Hillary D. Rodham (later Hillary Clinton), a future New York Senator, 2016 Democratic presidential nominee, and wife of President Bill Clinton, wrote her undergraduate thesis on Saul Alinsky in 1969 while attending Wellesley College in Massachusetts. Rodham had met Alinsky in 1968 and was able to interview him for the thesis. 107 The paper was unavailable to the public until 2001, after the end of Bill Clinton’s administration and Hillary Clinton’s first election to the U.S. Senate. 108

Entitled “There Is Only the Fight: An Analysis of the Alinsky Model,” the paper examines Alinsky’s life and philosophical themes revolving around power, moral relativism, radicalism, and use of Marxist terms to critique American society. “He is a neo-Hobbesian who objects to the consensual mystique surrounding political processes,” Rodham observed, “for him, conflict is the route to power.” “Alinsky is a born organizer who is not easily duplicated, but, in addition to his skill, he is a man of exceptional charm,” she further wrote. 109

Rodham observed that, while there is no fixed pattern for Alinskyite organizations, they tend to exhibit the following traits: 110

- “It is rooted in the local tradition” and relies on “the utilization of indigenous individuals” who “can be developed into leaders”;

- “Its energy or driving force is generated by the self-interest of the local residents”;

- It’s a product of a “series of common agreements” developed “hand in hand” with a “community council”;

- “It involves a substantial degree of individual citizen participation” from volunteers;

- It’s “as broad as the social horizon of the community” and avoids issues which garner narrow appeal;

- “It recognizes that a democratic society is one which responds to popular pressures, and therefore realistically operates on the basis of pressure”;

- “It gives priority to the significance of self-interest” channeled into a common direction “and at the same time respects the autonomy of individuals and organizations”;

- “It becomes completely self-financed at the end of approximately three years.”

She concluded: 111

“If the ideals Alinsky espouses were actualized, the result would be social revolution. Ironically, this is not a disjunctive projection if considered in the tradition of Western democratic theory. In the first chapter it was pointed out that Alinsky is regarded by many as the proponent of a dangerous socio/political philosophy. As such, he has been feared – just as Eugene Debs or Walt Whitman or Martin Luther King has been feared, because each embraced the most radical of political faiths—democracy.”

David Brock, a Republican-turned-Democratic political operative and later founder of the left-wing group Media Matters for America, called the by then Hillary Clinton “Alinsky’s Daughter” in his 1996 book The Seduction of Hillary Rodham. According to Brock, Rodham met Alinsky in Chicago in 1968 and studied his tactics, inviting him to speak at Wellesley College. 112

In 1969, Alinsky offered Rodham a paid position as a trainee with the Industrial Areas Foundation. She turned it down in favor of attending Yale Law School. “I remember him saying, ‘Well, that’s no way to change anything.’ And I said, ‘Well, I see a different way than you. And I think there’s a real opportunity,’” she told the Chicago Daily News in an interview in 1969. But she adopted many of his tactics, taking “her moral bearings from the radicals, while favoring establishment tactics—precisely the formulation she had told Saul Alinsky would be most effective.” 113

By the late 1970s, however, she had decided that “the key to achieving real social progress was not Alinsky-style agitation but skillful bureaucratic manipulation from inside.” Brock believes that her “tactical difference with Alinsky is what made Hillary’s radicalism much more effective, but also harder for the public to see.” 114

Barack Obama

Also see Barack Obama, Obama Foundation, and Organizing for Action

Barack Obama, later the 44th President of the United States, began his political career in the 1980s as a community organizer in Chicago, working for the Catholic-funded Developing Communities Project, an associate of the Gamaliel Foundation, which was founded by Saul Alinsky in 1968. Foundation director and lead organizer Gregory Galluzzo met the young Obama on “a regular basis as he incorporated the Developing Communities Project, as he moved the organization into action and as he developed the leadership structure for the organization. He would write beautiful and brilliant weekly reports about his work and the people he was engaging.” 115

Obama worked for Project Vote, an ACORN spin-off focused on voter registration and mobilization, just prior to attending law school in the early 1990s. Near the start of his presidential campaign in November 2007, he met with ACORN leaders and reminded them of his pas association: “I’ve been fighting alongside ACORN on issues you care about my entire career. Even before I was an elected official, when I ran Project Vote voter registration drive in Illinois, ACORN was smack dab in the middle of it, and we appreciate your work.” ACORN Votes, the group’s PAC, endorsed Obama for president in 2008. 116

Modern “Alinskyian” Organizations

Basic Features and Development of New Groups

Alinsky’s greatest contribution to politics is arguably the number of “Alinskyian” organizations he created, either directly or indirectly through his significant influence on 1960s and 70s political activism on the left-of-center. Groups like Midwest Academy, the Center for Community Change, Citizen Action/USAction/People’s Action (a succession of groups based on the same model), Interfaith Worker Justice, and UnidosUS (formerly National Council of La Raza) were all founded by Alinsky-trained activists and/or created along Alinsky-informed lines.

According to investigative reporter Stephanie Block, Alinskiyan organizations share some common characteristics. They generally prefer institutional members and members of religious bodies to sponsor the activist group because it affords the latter access to a pre-existing structure, funds, and “immediate moral credibility.” Alinskyian organizations with membership primarily drawn from religious bodies are referred to as “faith-based,” whereas those with largely secular membership are called “broad-based.” An Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) handbook explains: 117 118

“One of the largest reservoirs of untapped power is the institution of the parish and congregation. Religious institutions form the center of the organization. They have the people, the values, and the money.”

National representatives identify local leaders, train them in strategy, then hold neighborhood “values-clarification” meetings to discover issues of interest the organization may act upon. This can involve roleplaying sessions designed to draw out strong emotions. In one instance recorded in the book Cold Anger, which is commended by the IAF as accurate of its practices, an organizer reveals that an attending pastor’s son has meningitis, pressing the man’s “feelings of frustration and impotence” until the pastor “articulates his anger with God and with the ‘system’” for failing to aid his son—opening the possibility for recruiting him in a campaign targeting health insurance providers. 119 120

“The point is to get a number of people from member institutions interested in and supportive of the local organization,” Block writes. “In other words, the meetings are not designed to let local people determine the direction of the new community organization. Rather, they assist the organizers in planning the organization’s next level of activity . . . it is the agenda of the Alinskyian lead organizers, operating as managers of the national network, who determine where the network is going, what projects it supports, and what its foundational political ideology is—and therefore, how the work of its local affiliates support the national network’s goals.” 121

Block notes that, while Alinsky himself always emphasized local (“grassroots”) control over public affairs, most modern left-wing community organizers have adopted the term “grassroots” to falsely describe large, centralized activist centers headquartered in state capitals and Washington, D.C. whose lobbying focuses on federal programs. However, Alinsky created the template for national groups to identify local expansion targets rather than waiting for those residents to organize themselves, training local leadership to support the national group’s agenda. 122

Gamaliel Foundation

Also see Gamaliel Foundation

The Gamaliel Foundation was founded in 1968 by Alinsky and Gregory Galluzzo, a former Jesuit priest trained by Alinsky in community organizing tactics. Although the organization is named for Gamaliel, a Pharisee named by the Apostle Paul as the latter’s teacher and considered by Alinsky to be an early community organizer, it did not become an officially faith-based group until 1986. The Gamaliel Foundation is especially active in lobbying for left-wing policies in healthcare reform, and was part of the coalition Health Care for America Now (HCAN) responsible for urging the Democratic Congress to pass Obamacare legislation in 2010. 123

The Gamaliel Foundation has grown to become a network of 60 independently funded affiliate organizations in 18 states, with international affiliates in Great Britain and South Africa. 124 125

ACORN

Also see ACORN

One of the most prominent — though now defunct — Alinskyan organizations was the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN). From its creation in 1970, ACORN mirrored the Industrial Areas Foundation but with a key difference: “ACORN organizes communities; we don’t organize industrial areas,” in the words of one activist. Unlike most Alinsky-influenced groups, ACORN’s membership was drawn from secular bodies. 126