The Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) is a minor left-wing political party in the United States that was created in 1921 as the result of a forced merger between two rival communist factions, each founded in 1919. As of 2014 it reported only a few thousand members and two full time employees working in a New York City office. Once on the extreme-left fringe of American politics, the modern CPUSA engages in mostly conventional advocacy of left-wing policy and politics. “The positions they take are really indistinguishable from the left-wing social democratic groups,” said historian Ron Radosh to the BBC in 2014. “I don’t even know why anyone belongs to it.” 1 From the late-1930s through the end of 1948, the CPUSA exerted measurable influence within the left-leaning factions of the Democratic Party and large labor unions associated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (a predecessor organization to the modern AFL-CIO), such as the United Auto Workers (UAW). 2 CPUSA membership in the late-1930s was as high as 82,000. 3

The 1921 merger creating the CPUSA was ordered by the Communist International (Comintern), an organization controlled entirely by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), the political faction that ruled Soviet Russia (later the Soviet Union). At its founding convention, the CPUSA declared the “inevitability of and necessity for violent revolution” and that the party would prepare for “armed insurrection as the only means of overthrowing the capitalist state.” The CPUSA’s long-term goal of violently overthrowing the American government and capitalism was removed in 1935, on orders from the Comintern, due to the Soviet Union’s concern over the growing threat of Nazi Germany and a desire to form alliances with the capitalist nations (such as President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal Democrats in the United States) against fascism. 4

Throughout its history, until the demise of the Soviet Union and its ruling communist party in 1991, the CPUSA would continue to adhere to the foreign policy of the Soviet Union regarding when to radically and abruptly shift between participation in (or antagonism towards) mainstream American political institutions. Notable examples of CPUSA shifts in alignment with Soviet doctrine include the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in 1939, after which the CPUSA shifted from cooperation with FDR’s administration to hostility toward it; Nazi Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, after which the CPUSA was ordered to return to its cooperative attitude toward FDR and his allies; and the outbreak of the Cold War after 1945, when the CPUSA adopted an adversarial attitude toward the administration of President Harry Truman. 5

From the late 1920s and through the Cold War, the CPUSA and its highest officers provided substantial assistance to Soviet espionage agencies spying on the United States, leading historians Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes to state that it was “a fifth column working inside and against the United States in the Cold War.” 6 Soviet archives unveiled after the Cold War revealed that between 1971 and 1990 the CPUSA had received subsidies of $40 million from the Soviet Union. 7

Founding: 1919-1921

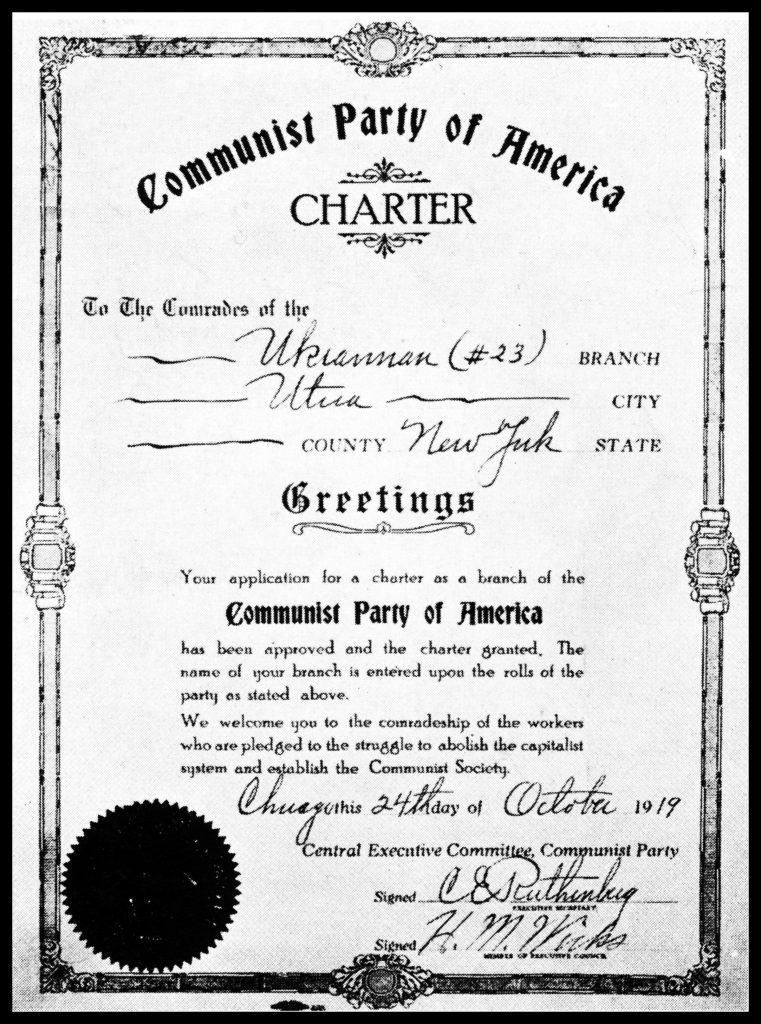

The Communist Party USA (CPUSA) was created in 1921 as the result of a forced merger between two rival communist factions in the United States (the Communist Labor Party of America and the Communist Party of America), both of which had been founded in 1919. At its founding convention/merger the CPUSA affirmed the “inevitability and necessity for violent revolution” and vowed to prepare “workers for armed insurrection” against the “capitalist state.” 8

The merger was ordered by the Communist International (Comintern), an organization purportedly comprised of co-equal communist parties from many nations that was in reality controlled entirely by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) – the political faction that ruled Soviet Russia (later the Soviet Union) from 1917 until 1991. The new organization, initially adopting the “Communist Party of America” name, was rebranded in 1929 as the Communist Party USA. 9

As a member of the Comintern, the CPUSA was subservient to the communist revolutionary government of the Soviet Union. Historians Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes wrote that “from the beginning the Russian party ran, not just led, the Comintern,” and that the Comintern evolved “particularly under Stalin” to become “little more than the Soviet Union’s instrument for directing foreign Communist movements.” The Americans “believed their party to be in possession of scientific truth” and “had not only an arrogance peculiar to true believers, but also a fierce commitment to the Soviet Union as the fount of that truth.” 10

Historian Guenter Lewy wrote that a 1920 “statement of principles” from the Comintern “imposed upon all member parties a system of strict discipline and subservience” and that the “national parties in the various countries were to be but separate sections of a worldwide revolutionary army led by a general staff in Moscow.” As such the leadership of the American branch “took pride in their faithful adherence” to the “organizational center of the Communist movement” and exhibited a “slavish adherence” to the Comintern. Lewy quotes a 1925 statement from William Z. Foster, a long-time CPUSA executive, who proclaimed “if the Comintern finds itself criss-cross with my opinions there is only one thing to do, and that is to change my opinions and fit the policy of the Comintern.” 11

Socialist Roots

Prior to merging to form what became the CPUSA, the Communist Labor Party of America (CLP) and the Communist Party of America (CP) had themselves evolved from the far-left factions of the American Socialist Party and other socialist movements. With an explicit goal of working within the U.S. political system and American labor unions, the Socialist Party of America had grown to more than 118,000 members by 1912; Socialist candidate Eugene V. Debs had attained 6 percent of the popular vote in that year’s U.S Presidential election. 12

However, the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia inspired the most left-wing socialists in the United States to adopt instead the revolutionary goal of overthrowing the American state as the Bolsheviks had done in Russia. The Bolsheviks had leveraged a group with just 11,000 members at the start of 1917 into a movement that took command by the end of the year. The 1919 founding manifesto of the Communist Party of America faction that would later merge into the CPUSA read: “Communism does not propose to ‘capture’ the bourgeoisie parliamentary state, but to conquer and destroy it.” 13

After 1917 some left-wing American socialists (at this point effectively communists) initially tried to take command of the Socialist Party, its valuable newspapers and its infrastructure. The moderate faction within the Socialist Party, seeking to retain the commitment to representative democracy and working within the labor union movement, successfully repelled the communist takeover effort. But the price of this victory was a steep drop in support: While it had more than 109,000 members at the start of 1919, the Socialist Party had just over 39,000 remaining by that summer. 14

Foreign Membership

One factor leading to the schism of two different American communist parties being born in 1919 involved differences of opinion over whether to attempt a takeover the Socialist Party. Another fault line ran between native-born and foreign-born factions of the left-wing socialist movement – including a very influential “Russian federation” – each of which had its own separate socialist organization based on a foreign, non-English language. 15

The foreign language subdivisions survived the 1921 merger that created the CPUSA, with an estimated 90 percent of early party membership being foreign-born. The foreign language subdivisions were abolished in 1925, but the controversial policy led to a loss of nearly 50 percent of the party’s membership within one month. By 1929, party members speaking a language other than English still comprised about two-thirds of the total. Not until October 1936 were a majority of CPUSA members native-born Americans. 16

Lenin Demands Pragmatism

Unbeknownst to both American communist factions, their decision to fight against representative government and trade unions was at odds with Comintern policy even before their merger. In 1920, Russian communist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin ordered what historians Klehr and Haynes referred to as “pragmatic tactics to advance the Communist cause” within a “nonrevolutionary environment” that “blatantly conflicted” with the path the nascent American party factions were on. Rather than trying to destroy the non-communist labor unions, Lenin ordered communist parties to work within what he called “reactionary trade unions.” And rather than seeking destruction of democratic political systems as their primary goal, Lenin demanded communist parties to participate in elections. 17

At the 1921 convention merging the rival factions and creating what would later become known as the CPUSA, the American communists also adopted the pragmatic tactical course demanded by the Lenin-led Comintern. This represented both an abrupt reversal of direction regarding the American communist policy toward organized labor. Just two years earlier during a major steel strike in 1919 both competing communist factions had denounced the American Federation of Labor (AFL, a predecessor of the modern AFL-CIO) and the head of its strike committee, William Z. Foster, for pursuing standard labor union concerns such as higher wages, better working conditions, and recognition of the union rather than turning the dispute into a “general political strike that will break the power of Capitalism and initiate the dictatorship of the proletariat.” The rival communist factions had also pledged to destroy the AFL. Yet, shortly after their merger it was none other than Foster who emerged as a Comintern-approved leader of the American Communist movement. 18

Further elaborating on his pragmatic points in 1921, Lenin (via the Comintern) ordered the subordinate communist parties to de-emphasize their secretive and subversive planning for imminent revolution and instead form vote-seeking political parties. In response to Lenin’s new marching orders the CPUSA “unconditionally” and “without reservations” stated it would begin to operate openly within the political system. 19

First Decade: 1920s

Due to its subservience to the Comintern and by extension the leadership of what became known as the Soviet Union, the first decade of the CPUSA (known until 1929 as the “Communist Party of America”) was marked by sudden and radical reversals in doctrine.

In 1923 the CPUSA under top leaders such as William Z. Foster began working cooperatively with a coalition of socialists and other left-wing unions and organizations moving toward supporting what would become the independent, left-wing, 1924 U.S. Presidential bid of Wisconsin U.S. Sen. Robert La Follette. At the time this effort to work with the non-communist American left was fully in keeping with the 1920-21 policies ordered by Lenin through the Comintern. 20

Lenin died in January 1924. A severe and ultimately murderous rivalry to replace him ensued between factions led by Leon Trotsky and the eventual victor, Joseph Stalin. This touched off several sudden reversals and counter-reversals of the Soviet orders being sent to the CPUSA.

Trotsky’s faction staked out a hardline-left revolutionary position and denounced the Comintern policy of working with non-communists, specifically criticizing the CPUSA’s flirtation with the La Follette movement. To prevent Trotsky from outmaneuvering them from the hard left, Stalin’s camp responded by changing Comintern policy so that the CPUSA’s new direction would be to cease its outreach to the La Follette camp. 21

With all rivals in Moscow now opposed to cooperation with La Follette, the CPUSA abandoned its alliance with his coalition, and during the 1924 election ran William Z. Foster as the CPUSA’s own presidential candidate. According to historians Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes, the “Communists spent more time attacking La Follette than they did criticizing the Republican or Democratic candidates.” The Communist ticket received approximately 33,000 votes. 22

But then in 1925, with Stalin needing to cement different political alliances in his bid to consolidate power, he ordered the Comintern to lurch back again in the direction it had just abandoned. Nicolai Bukharin, a vital Stalin ally in the battle to purge Trotsky, favored a moderate course for the Comintern. According to Klehr and Haynes, the “Comintern, which had insisted on the break with La Follette, looked back and decided that La Follette had represented a forward step for America.” The CPUSA was once again told to work within non-communist labor unions and other institutions on the American left. 23

With this change, at the August 1927 CPUSA convention a faction led by party apparatchik Jay Lovestone swept to power. Lovestone was an ally of Bukharin and the moderate, accommodationist side of the Comintern’s frequently split personality. The 1925 flip-flop in Comintern policy also led to successful communist inroads being made into other labor organizations, such as the Fur Workers Union and the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. 24

But by 1928 Stalin was feuding with Bukharin, touching off yet another reversal in Comintern policy, this time against the moderation of Bukharin and his allies. The CPUSA was ordered to cease working with non-communist organizations and instead build parallel institutions that would prepare the way for the anticipated revolution and battle to defeat capitalism. Stalin personally intervened to make sure the previously “in-favor” Lovestone was booted from his leadership position in the CPUSA and expelled from the party itself. 25

The doctrinally flexible William Z. Foster was once again the CPUSA presidential candidate in 1928. Reflecting the return to favor of hot, revolutionary-left rhetoric, he told a cheering crowd at a rally that a “Soviet” government was destined to rise in the United States and that standing behind it would be “the Red Army to enforce the Dictatorship of the Proletariat.” This time the Communist ticket received a little more than 48,000 votes, small in comparison to even the Socialist Party ticket’s 268,000. 26

Prior to the 1928 reversal of Comintern policy, labor union activists from the CPUSA had been making inroads toward gaining influence over the United Mine Workers (UMWA). The Comintern’s new, revolutionary-militant instructions put a stop to working within the UMWA and led to the communists creating a rival union – the National Miners Union. In keeping with the policy of non-cooperation the communists established many other alternative unions to compete with non-communist, established labor organizations. 27

According to Klehr and Haynes, CPUSA membership fluctuated throughout the 1920s in reaction to both economic conditions and the fickle directives of the Comintern. A rough economy and/or orders from Moscow to cooperate within the system would lead to a boost in CPUSA membership, while the opposite conditions would reduce the membership list. The historians estimate no more than about 10,000 people were CPUSA members during the years 1927-1930, with the heaviest concentrations in big midwestern and northeastern cities such as New York City, Boston, Detroit, Cleveland, and Chicago. 28

In Hollywood, according to Klehr and Haynes, the CPUSA’s labor union officials also “struck pay dirt” as actors, actresses, and screenwriters joined the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League (a CPUSA front) and communist organizers were a “strong force” in many Hollywood unions, in particular the Screen Writers Guild (now the Writers Guild of America, West and Writers Guild of America, East). 29

Early ‘Red Decade’: 1929-1935

The October 1929 crash of the U.S. stock market and Great Depression that followed shortly afterward led to the Communist Party USA’s most successful decade. Describing demonstrations organized by the communists in the early years of this decade and other programs, historians Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes characterized the CPUSA as the “boldest and most visible opponent of American capitalism” and either the “only” or “most effective” protest outlet during the tough economic environment. 30

CPUSA-directed International Unemployment Day demonstrations in March 1930 drew an estimated 1 million participants across many cities, with a riot at the New York City demonstration leading to 100 injuries (Klehr and Haynes write that the demonstrations were designed to generate conflicts with law enforcement). Though subsequent demonstrations drew much smaller crowds, the CPUSA-led National Campaign Committee for Unemployment Insurance registered 1.4 million signatures for a petition demanding Congress enact the program. In many cities, according to Klehr and Haynes, CPUSA activists placed themselves “at the forefront” of efforts to assist the poor, leading rent strikes and fighting against evictions. 31

Tactics and Leadership

Though still finishing far behind the Socialists in the 1932 U.S. Presidential race, CPUSA candidate William Z. Foster more than doubled the party’s vote total (as compared to 1928) to more than 102,000. The vice-presidential slot on the ticket was held by James Ford, the first black candidate placed on a national ticket in the 20th century. The CPUSA platform included planks supporting the Soviet Union, unemployment insurance, and equal rights for black Americans. 32

The 1932 ticket was endorsed by more than fifty public intellectuals banded together under the League of Professional Groups (one of several CPUSA front organizations). During the September before the election, several major newspapers carried a statement from the entire group praising the Communists as the party proposing the “real solution” of overthrowing capitalism and denouncing even the Socialists as “the third party of capitalism.” Signatories included writers John Dos Passos, Waldo Frank, and Sidney Hook, each of whom would later become critics of the CPUSA. 33

Another campaign pamphlet released by the CPUSA front group for intellectuals said socialists – by supporting democracy – were “indirectly helping fascism.” 34

The uncompromising rhetoric, mirroring the latest change in attitude directed by Stalin in 1928, was typical of the CPUSA during the first half of the decade. For the 1932 presidential race Foster released a campaign book titled Toward Soviet America in which he stated a civil war was needed to destroy capitalism and that the CPUSA’s aim was to replicate the single-party rule of the communists in Soviet Russia. In July 1933, the CPUSA denounced newly elected Democratic President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal as a step in the direction of fascism, and even socialist writer Upton Sinclair was branded a “fascist” after winning the 1934 Democratic gubernatorial primary in California. 35

Similarly, “Dual Unionism” – the CPUSA’s strident and confrontational effort during the first part of the decade to compete with and replace established labor unions – largely failed. The Trade Union Unity League (TUUL) was a CPUSA front group created in 1929 with the goal of wiping out what it said was the “fascist” American Federation of Labor. But among TUUL’s doctrinal and tactical failings was too much of a focus on big policy goals (such as passing unemployment insurance), or even bigger revolutionary objectives (establishing worker-led governments) and too little emphasis on the bedrock wage and working condition concerns of workers. In the major American labor strikes that occurred during 1934, CPUSA/TUUL unions were not a major factor. 36

In 1934, with Foster in poor health, Earl Browder was selected leader of the CPUSA and would remain as such for the next decade. 37

Popular Front: 1935-1939

The rise and growing strength of Nazi Germany throughout 1933 and into 1934 began to alarm Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, leading him to seek out allies to protect the Soviet Union. Looking to the American government itself as a potential ally, Stalin’s new agenda for the CPUSA would mean yet another pivot away from confrontation with American labor unions and the non-communist left, and toward an unprecedented era of cooperation known as the “Popular Front.” The result, according to historians Klehr and Haynes, was that from “late 1935 to 1939” the CPUSA “enjoyed the greatest successes in its history, never to be matched again.” 38

During summer 1935, the Soviet-controlled Comintern adopted the Popular Front and ordered the communist parties of the world to seek common alliances against fascism with left-leaning, non-communist parties and organizations. The CPUSA was ordered to make common cause with President Roosevelt against his political enemies. This unprecedented demand required the CPUSA to cease its open advocacy for overthrowing the American political system and instead cooperate with the mainstream left of the USA’s two-party system. In response, American communists ceased denouncing Roosevelt as the “leading organizer and inspirer of Fascism” and his White House as the “central headquarters of the advance of fascism.” By 1938 CPUSA leader Earl Browder was praising FDR as “the symbol which unites the broadest masses of the progressive majority” and the President was accepting honorary membership in the League of American Writers – a cultural front group run by the CPUSA. 39

The Socialist Party in the United States ultimately declined to join the Popular Front. Historian Guenter Lewy has written that the birth of the Popular Front, arguably a shift to the ideological right by the CPUSA, occurred just as many American Socialist Party leaders were moving left and growing hostile to Stalin’s brutal leadership of the Soviet Union. Though the CPUSA had shifted to supporting FDR and the New Deal, Socialists, including party leader and perennial Presidential candidate Norman Thomas, remained opposed to both. Toward the end of the decade, after becoming aware of the brutality of the Stalinist regime, Thomas denounced both fascism and communism as totalitarian ideologies, and opposed the Soviet-created Popular Front. 40

Membership and Electoral Success

CPUSA membership jumped after the party aligned with FDR, going from 30,000 in 1935 to 82,000 by 1938. Historians Klehr and Haynes have identified the party’s “greatest” recruiting success during this period as among Jewish Americans, due in large measure to the CPUSA’s apparently uncompromising opposition to Nazism. After 1936, the Soviet Union’s support for the left-wing Republican (anti-fascist) side of the Spanish Civil War, against Francisco Franco’s Nazi-supported Nationalists, also helped the CPUSA recruit American leftist radicals, with noticeable membership increases among professionals such as doctors, lawyers, and teachers. 41

The communists also improved their electoral success after alignment with the New Deal and FDR. CPUSA presidential candidate Earl Browder declined to attack Roosevelt during the 1936 election and focused his criticisms instead on Republican nominee Alf Landon. While this slightly depressed the CPUSA vote total for President, it increased the party’s influence within mainstream politics. For example, working within Democratic Party politics, after 1935 more than a dozen undercover CPUSA members were elected to the state legislature in Washington. At the same time the Socialist Party, unable to serve as a magnet for anti-Nazi, left-wing radicals who supported the New Deal, saw its presidential vote total fall by 80 percent in 1936 as compared to four years earlier. 42

Labor Union Infiltration

Just prior to the policy that evolved into the Popular Front, the Soviet Union (through the Comintern) told the CPUSA to shut down its unsuccessful effort to compete with non-communist labor unions and begin working again within the non-communist unions. The so-called “dual unionism” program and its “independent” CPUSA-controlled unions were disbanded by March 1935. 43

In conjunction with the Popular Front’s focus on accommodating FDR and the New Deal, the CPUSA found success in its efforts to infiltrate and influence the non-communist labor union movement. The biggest and most important opportunity occurred in 1935 when a disgruntled American Federation of Labor executive resigned to form the rival Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and did so with strong assistance from the former organizers of the Trade Union Unity League (TUUL), the CPUSA’s recently disbanded dual-unionism front. As a result of this collaboration, Klehr and Haynes estimate that by the end of the decade 40 percent of CIO unions had “significant communist connections.” The CIO would live on into the 1950s and merge with the rival AFL to become the modern AFL-CIO. 44

The Steelworkers Organizing Committee (SWOC) was one significant success for the CPUSA’s work within the CIO. Klehr and Haynes write that at one point more than one quarter of SWOC organizers were CPUSA affiliated, with one secret communist official serving as SWOC counsel and later holding the same position with the CIO. The SWOC was the precursor to the United Steelworkers. 45

The United Auto Workers (UAW) was another source of some early success for CPUSA infiltration within the CIO. Communists held leadership roles in the December 1936-February 1937 “Sit Down Strike” at a General Motors plant in Flint, Michigan, which led to recognition of the UAW by GM and Chrysler. Battle for control of the UAW between communist and non-communist leaders ended when non-communist Walter Reuther’s slate won control of the union in the 1940s. 46

Klehr and Haynes estimate that labor union members comprised 40 percent of CPUSA membership during the Popular Front heyday, with most of these being from CIO-affiliated unions. Some other noteworthy unions with CPUSA officials holding leadership positions during this era included the Transport Workers Union and the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers Union.47

Nazi-Soviet Pact: 1939-1941

The Popular Front and the so-called ‘Red Decade’ for the Communist Party USA ended on August 24, 1939, with the announcement that the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact – a non-aggression treaty between Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin and Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler – had been signed the day before. In addition to other provisions regarding the conquest of several European nations, the agreement stipulated that the former (and future) adversaries would divide the territory of the Republic of Poland. The agreement cleared the way for the Nazi invasion of Poland on September 1, leading to declarations of war against Germany by the United Kingdom and France, starting World War II in Europe. In the weeks that followed – and in keeping with the terms of its agreement with Hitler – the Soviet Union would invade Poland from the east and occupy the Baltic States and other territories. 48

After the Nazi attack on Poland, the Comintern ordered the Communist Party USA to cease its support for the New Deal and break its alliances with FDR. Moscow replaced the CPUSA’s Popular Front policy that had stridently opposed the Nazis and fascism and sought alliances with capitalists to resist Hitler since 1935 with a demand for the American party to agitate for neutrality in the war between Nazi Germany and the United Kingdom and France. Once again, the CPUSA began to associate FDR with fascism, and CPUSA-controlled newspapers stated that Britain and Nazi Germany were equally evil and declared Great Britain to be “the greatest danger to Europe and all mankind.” 49

The CPUSA’s abrupt change of course regarding hostility to the Nazis inflicted severe damage on the reputation it had built up during the Popular Front years. Historians Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes wrote that the Communist Party USA had “demonstrated that none of its principles was as precious as loyalty to the foreign policy of the Soviet Union.” Many of the party’s front groups opposing fascism fell apart or experienced large drops in membership. Klehr and Haynes reported that the National Lawyers Guild “lost virtually all of its liberal members” and the League of American Writers lost so many of its prominent names that “its letterhead had to be abandoned.” Overall membership and mainstream political influence declined sharply, with Jewish members leading the way out. 50

Browderism: 1941-1945

Return of Popular Front

Nazi Germany abrogated the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact when it attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941. Historians Klehr and Haynes wrote that this caused the policy of the Soviet Union and thus the Communist Party USA under its control to shift yet again “from uncompromising opposition to U.S. involvement in World War II to fire-eating support for American intervention.” In December 1941, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the declaration of war on the United States by Nazi Germany, the United States joined the war as an ally of the Soviets against the Nazis. 51

The CPUSA, led by Earl Browder, began to aggressively re-establish the Popular Front policy, winning back some of the support and influence it had squandered after the Nazi-Soviet agreement.

Historian Guenter Lewy wrote that labor unions controlled by CPUSA leadership insisted that all disputes with management be resolved “without interruption in production” and developed better “no strike” records than unions ruled by non-communists. Browder himself “proudly agreed” to the label of “strikebreaker.” Unions seeking to strike during the war were labeled by the CPUSA leaders as “agents of Hitler.” 52

By the end of the war influence within the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) had grown to the point where nearly 1.4 million union members (about 25 percent of the total) belonged to CIO affiliates whose leadership was aligned with the CPUSA. But by this point the CIO had drifted far enough into the mainstream of the American labor movement that the CPUSA factions within the CIO were allies of the most centrist and largest faction within the organization. The CIO-PAC had become a donor to the reelection of FDR in 1944. 53

The CPUSA also began working agreeably to help Democrats and left-of-center non-communists win political offices further down the ballot. In 1944 it convinced Minnesota’s Farmer-Labor Party to merge with the mainstream Democrats. And Klehr and Haynes write that CPUSA members were among the “staunchest supporters” of former California Lt. Gov. Ellis Patterson (D) during his successful 1944 campaign for a U.S. Congressional seat. 54

Edging their way into the political and labor mainstream, by 1944 CPUSA membership had doubled from 1941 levels. Demonstrating their appeal, Guenter Lewy wrote that “government officials, senators, congressmen, generals, and captains of industry supported Communist fronts even when Communist dominance was only thinly disguised.” 55

The battlefield and home front sacrifices made by the people of the Soviet Union in their fight against Hitler also won sympathies with Americans, sentiments which assisted the cause of the Communist Party USA. The subject of a March 1943 issue of Life magazine heaping praise on the Soviet people was “Soviet-American cooperation.” Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin’s oppressive secret police (the NKVD) were compared favorably by Life to the American FBI as merely another organization with the job of hunting down traitors. 56

Brief Abolition of the CPUSA

As the successful period of wartime collaboration with the mainstream of American institutions continued, Communist Party USA chief Earl Browder moved the CPUSA to both solidify the drift toward the center and enhance it. In a unanimous May 1944 vote at its convention, the Communist Party USA abolished itself and reconstituted as the Communist Political Association (CPA). The preamble to the new organization reiterated its support for socialism and Marxism, but also praised the U.S. Constitution and Declaration of Independence, American presidents and patriots such as Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln and Thomas Paine, and the “achievements of American democracy.” 57

Rather than seeking the violent overthrow of capitalism, once the goal of the CPUSA, the CPA would look to “the family of free nations, led by the great coalition of democratic capitalist and socialist states, to inaugurate an era of world peace, expanding production and economic well being.” The CPA pledged expulsion as the punishment for members who advocated overthrowing the U.S. government or destroying its institutions and was designed to work exclusively within the American two-party system. Unlike the CPUSA, the CPA would not offer its own third-party slate of candidates. 58

Browder’s motive for creating the CPA was the belief that the wartime alliances of Britain and the Americans with the U.S.S.R. demonstrated the capitalist west was no longer seeking the destruction of the Soviet Union, and that western Europe would likely be “reconstructed on a bourgeois-democratic, non-fascist capitalist basis, not upon a Soviet basis.” He said Communists were “ready to cooperate in making this capitalism work effectively.” The 1944 CPUSA/CPA convention took place underneath photos of FDR, United Kingdom Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Joseph Stalin. 59

Guenter Lewy wrote that Browder had reason to believe this strong push toward the center was in keeping with what Stalin desired at that point in time, saying it “furthered Russia’s goal of strengthening the wartime alliance.” 60 One year earlier in May 1943 Stalin made his own contribution to this perception by abolishing the Comintern and no longer encouraging international communist allies such as the CPUSA to seek the overthrow of their homeland governments. 61

But one year later, in May 1945, with World War II nearing its end and the threat of Nazi Germany to the Soviet Union extinguished, Stalin’s need to appease his wartime allies was also in retreat. In the interpretation of historian Guenter Lewy, Stalin had been “encouraged by the weakness displayed by Roosevelt and Churchill at the Yalta conference in February 1945” and had adopted a new “hard line” that was aiming toward what would become the Cold War. 62

The new “hard line” swiftly led to total abandonment of both Browder and his Communist Political Association. In April 1945 a high-ranking official in the French Communist Party denounced the Browder-led dissolution of the CPUSA as a “notorious revision of Marxism.” According to Lewy this was interpreted by CPUSA/CPA members to be a Moscow-directed criticism, and the Americans responded to the hint. A July 1945 meeting unanimously abolished the CPA, re-established the Communist Party USA, and stripped Browder of this power within the CPUSA. 63

In Lewy’s analysis the fall of Browder “once again demonstrated [the CPUSA’s] total dependence on their Russian masters.” The party officials who had just a year earlier unanimously supported Browder now denounced “Browderism” as a “dangerous heresy” and “repudiated him and his policies in an orgy of confession and self-abasement.” In February 1946, Browder – having been branded a “social imperialist” by his former allies – was purged from the CPUSA. 64

Early Cold War: 1945-1960

Following the revival of the Popular Front during World War II, the political, labor union and financial strength of the Communist Party USA was at another high point during the first few postwar years – a successful era never again to be repeated. “Until 1949,” historians Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes have observed, “one could reasonably view the Communist party, by reason of its institutional strength, political influence, totalitarian goals, links to Soviet foreign policy, and habitual concealment as a threat to American democracy.” Among the advantages cited were unprecedented financial power and “institutional power through the labor movement.” 65

With the dissolution of the Comintern in 1943, the CPUSA no longer had a direct line of authority up to orders from the Soviet Union. But Klehr and Hanyes, quoting other historians and former American communists, define this era as one of a “mental Comintern” for the CPUSA leadership. American communist party members continued to draw their policy and tactical guidance from the Kremlin, but used “indirect” means to acquire it, such as reading the official Soviet media reports and other clues. 66

Following the purge of Earl Browder from leadership, the CPUSA appointed Eugene Dennis as its general secretary in 1946. William Z. Foster, in ill health, held onto a leadership title as party chairman, but Dennis became the operational commander. Dennis had a background as a long-serving and loyal Comintern agent, having represented the Soviet agency in several nations and under different aliases. He was described by Klehr and Haynes as an “exemplary Communist bureaucrat” and “Moscow loyalist who abandoned Browder at the right moment.” 67

Troubles with Truman

Democratic President Harry Truman’s ascension to the office in 1945 roughly coincided with the purge of Earl Browder (and his moderate policies) from the CPUSA, the end of World War II, and foreign policy disagreements with the Soviet Union that soon became the Cold War. The relatively peaceful cooperation between the White House and the CPUSA that had taken place during the war ended as these factors swiftly pushed Truman into conflict with the labor unions and left-wing political factions aligned with the CPUSA. 68

After the war ended, Truman faced a wave of labor strikes. Truman responded by imposing federal control over U.S. railways in 1946, seeking to block a strike by railroad workers, causing the leader of one union to announce that labor should campaign for the defeat of Truman if he pursued reelection in 1948. Likewise, resolutions demanding a breakaway political party run by labor unions were approved at conventions of the Congress of Industrial Organizations. 69

The average American’s sentiment toward the Soviet Union turned negative after World War II as Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin suppressed democracy in the Soviet-conquered nations of Eastern Europe and began turning them into communist satellites. As this was occurring, American government officials were unearthing the earliest evidence of Americans spying for the Soviet Union. 70

At the same time, Communist Party USA officials were becoming more strident in their support for Stalin and denouncing the United States for imperialism.

William Z. Foster declared the United States to have more “all-inclusive imperialist goals” than any nation in history – even worse than the Nazis and Imperial Japan – and praised the Soviet Union as the only impediment to those goals. Foster charged American communists as having a unique place in the supposed “world crisis” as the “axe that must be applied to the root of the evil,” and that “the power of finance capital, the breeder of economic chaos, fascism and war, must be systematically weakened and eventually broken.” A high-placed Foster lieutenant revered Stalin’s “greatness and genius” and the most prominent CPUSA female official praised the Soviet dictator as “the best loved man on Earth.” 71

These trends caused Americans, including a growing number of left-leaning Americans, to adopt a much more negative attitude toward the CPUSA and led the CPUSA and its allies to become more antagonistic toward Truman. After Democratic setbacks during the 1946 elections, including the loss of Congress to Republicans, a coalition of prominent left-liberal Democrats, including former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, formed Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) with the aim of pushing Democrats to become a resolutely anti-communist and anti-Stalin party. 72

The 3rd Party Split

The purging of Earl Browder and his plan to have the Communist Party USA work within the American two-party system as the re-flagged “Communist Political Association” was followed in November 1945 by Eugene Dennis laying out the opposite strategy, proposing the creation of a third major political party comprising a large left-wing coalition led by labor unions and the CPUSA. Dennis declared the nation needed something more than the “two-party straight-jacket” and should be “in a position to have a choice in 1948 between a Truman and a Dewey.” This plan would culminate in the CPUSA and its closest allies on the left coalescing behind the 1948 Progressive Party campaign of former Democratic Vice President Henry Wallace. 73

However, recognizing the hostility toward President Truman growing within the labor unions and other left-wing constituencies within the Democratic Party, Dennis initially kept open the option of working within the two-party system one last time if a coalition could be created to replace Truman with Wallace as the Democratic nominee. Much of the leadership of the unions within the Congress of Industrial Organizations – including those affiliated with the CPUSA – agreed with the plan to keep options open. Saying the CPUSA was not full of “irresponsible sectarians,” Dennis criticized the “launching of premature and unrepresentative third parties.” 74

By 1947 Wallace had become the choice of the anti-Truman left, including the CPUSA and its allies in labor. But through most of the year Wallace and his supporters – including top leaders in the CPUSA – remained open to the potential of restricting their challenge to Truman within the Democratic Party’s nomination process. A decision against a third-party challenge was being strongly pushed by most officials within both the CIO and the American Federation of Labor. Republicans had won control of Congress during the 1946 election and passed the Taft-Hartley Act over Truman’s veto to challenge the power of unions and expel Communists from the labor movement. The potential for a Republican winning the presidency in 1948 left labor bosses worried that a third-party presidential challenge from the left in 1948 ran too high of a risk of stealing votes from the Democratic candidate. 75

In October 1947 the Soviet Union announced creation of the Communist Information Bureau (Cominform), a linkage of European communist parties against so-called “American imperialism” and the U.S.-sponsored Marshall Plan to help rebuild the destroyed economies of Europe. The Cominform also denounced the French and Italian communist parties for failing to seize power after their nations had been liberated from the Nazis. 76

Interpreting these developments as an implied directive from the Soviet Union to become more confrontational toward conventional American political parties, CPUSA leaders informed their allies within labor unions to endorse a third-party challenge from Wallace, even if the price was the rupturing of the alliances the CPUSA had built within the unions. 77

Wallace, though not a communist, listened to the changed attitude from those affiliated with the CPUSA and made his own decision to pursue a third-party challenge. This turned up the heat on an already consequential showdown with the communists happening within both the Democratic Party and the American labor movement. 78

Anti-communist Walter Reuther won the presidency of the United Auto Workers (UAW) in 1946, but CPUSA-affiliated members retained their place within a broader coalition that ruled the union’s executive board. This ended with the 1947 UAW elections, in which Reuther’s anti-communist faction won big and set about ejecting CPUSA members from all positions of authority within the labor organization. In the aftermath of the CPUSA’s push for Wallace as a third-party candidate, similar elections and purges occurred within other CIO affiliate unions and the CIO itself. Klehr and Haynes write that “within weeks” of the Wallace decision CIO president Philip Murray had “severed the center-left alliance” within his union and “set about breaking the back of the [CPUSA] position in labor.” The result of this largely successful purge was an anti-communist majority – roughly three-quarters of CIO member unions – and a “shrinking Communist-aligned minority.” 79 Anti-Communist factions were also aided by a provision of the Taft-Hartley Act that required union officers to submit affidavits that they were not communists in order for their unions to seek redress for unfair labor practices before the National Labor Relations Board. 80

The Wallace challenge led to similar shakeups within the Democratic Party, as Americans for Democratic Action and other anti-communist left-of-center factions – including one headed by future Democratic vice president and presidential nominee Hubert Humphrey – feuded with and often successfully removed CPUSA influences. 81

Pressured to choose between Wallace on the one hand, and on the other retaining the power and careers obtained within labor unions and Democratic Party, only the most ideological CPUSA allies and members gave up their mainstream positions to stick with the Wallace insurrection. This produced a narrowing of Wallace’s support to a more and more strident CPUSA and left-wing base. Wallace exacerbated the trend by gaffes as a candidate that included defending the Soviet Union’s February 1948 coup against the democratically elected government of Czechoslovakia. 82

Wallace lost badly in November 1948 (with his “third-party” challenge finishing fourth with just 2.3 percent of the popular vote), and Truman was reelected. The combination allowed the victorious trio of Truman, the Democratic Party, and the anti-communist labor leaders to continue and decisively win the ongoing ideological battles against the CPUSA. The failure of the Progressive Party campaign, according the Klehr and Haynes, was a “decisive defeat” that “broke the back of communism in America” and by the early 1960s would leave the CPUSA “tiny” and “politically isolated,” with nearly all of its pre-1948 mainstream influence gone. 83

White Chauvinism Purges

The Communist Party USA responded to the failures from the 1948 election by turning on and blaming each other, with the so-called “white chauvinism” purges being the most destructive example. 84

The CPUSA was one of the first majority-white American political movements to mount a steady and deliberate outreach to black Americans. This produced modest but real returns by the end of World War II, at which point more than 10 percent of CPUSA membership were African Americans. This success coincided with the post-war emergence of nationalist liberation movements in Africa and other former and then-current colonial nations, leading some in the CPUSA to speculate on the possibility that non-white causes and communists were a revolutionary growth area deserving of more time and energy. 85

The potential of non-white communists transformed into a weapon for internal bickering after the failures of the 1948 election. Beginning in October 1949, CPUSA leaders set out to purify the party’s position regarding black liberation by purging alleged white racists from their membership. A CPUSA “confused and angry at political defeat and steeped in an apocalyptic expectation of world war and fascism in America,” according to historians Klehr and Haynes “took out their frustrations on white chauvinism.” 86

In his book American Communism in Crisis: 1943-1957, historian (and former CPUSA activist) Joseph Starobin wrote that the hunt for white chauvinists “wracked the lives of tens of thousands” as CPUSA leaders were “demoted from their posts for real or alleged insults.” Words such as “whitewash” and “black sheep” could raise suspicion as “both whites and blacks began to take advantage of the enormous weapon which the charge of ’white chauvinism’ gave them to settle scores, to climb organizational ladders, to fight for jobs, and to express personality conflicts.” 87

When it finally ended, according to Starobin, CPUSA members who had lived through it asked themselves “if they were capable of such cruelties to each other when they were a small handful of people bound by sacred ideals, what might they have done if they had been in power?”88

The ‘Red Scare’

While the actual power of the Communist Party USA by 1949 was very weak and declining, the party’s perceived power was exaggerated by both the CPUSA and its most strident opponents in the United States. The CPUSA, according to Klehr and Haynes, “saw themselves and were perceived as the American representatives of an international movement led by the Soviet Union.” With the world’s largest army, nuclear weapons, a collection of captive client states in Eastern Europe, and supposed allies winning or starting revolutions from China to Africa, the Soviet Union of 1949 posed a real threat, and those who recognized this had a tendency to erroneously credit some of that success to the CPUSA. 89

During the early 1950s Americans, through their elected representatives, moved to check the supposed threat posed by the CPUSA. They wanted domestic communism smashed, according to Klehr and Haynes, even though “it was not well understood” that “there was little left to smash.” The severity of this reaction was limited, however, as the historians have observed that even “during the peak of popular and official anticommunism in the early 1950s, the [CPUSA] organized public protests, supported its beleaguered labor allies, recruited new members (although not many), ran candidates for public office (not many of these either), and circulated hundreds of thousands of copies of its newspapers, pamphlets and books.” 90

As the Cold War began, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover sought and received expanded powers to investigate CPUSA members. Beginning in 1948 some of this information, and FBI informants within the CPUSA, were used in the prosecution and conviction of more than one hundred Communist Party USA members under the Smith Act, legislation passed in 1940 that made it a federal crime to advocate for the violent overthrow of the American government. Among the first dozen prosecutions were longtime top official William Z. Foster, current general secretary Eugene Dennis, and future general secretary and presidential candidate Gus Hall. 91

Less than a decade earlier during World War II, with the Soviet Union as an ally of the United States, CPUSA officials had supported the use of Smith Act prosecutions against left-wing rivals who opposed the war effort. Klehr and Haynes write that the CPUSA “applauded” the prosecution of Socialist Party leader (and presidential candidate) Norm Thomas because he opposed the war “on pacifist grounds.” 92 Fellow historian Guenter Lewy reports that in 1941 the Daily Worker (the CPUSA’s newspaper) “hailed the [Smith Act] prosecution” of 29 Trotskyite trade unionists (most of them from an International Brotherhood of Teamsters local in Minnesota) who opposed the war. 93

The legal strategy of the first eleven defendants (minus Foster, who had been excused from prosecution due to declining health) was to argue the CPUSA did not promote overthrow of the American government and that official party policy since the 1930s was to promote a democratic path to revolution. As evidence for its case the government presented the eviction of Earl Browder from the CPUSA (following his advocacy of working within the two-party system) and the text of Marxist-Leninist publications calling for revolution and still in use by the CPUSA. All eleven defendants were convicted in 1949, receiving sentences ranging from 3-5 years. The convictions were upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1951. 94

Subsequent Smith Act CPUSA defendants decided to argue their cases on First Amendment grounds and were more successful. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1957 Yates decision, voiding the Smith Act convictions of CPUSA members from California, resulted in many lower courts either reversing or dismissing similar cases. Klehr and Haynes write that by the end of the decade the Smith Act had “ceased to be an effective weapon” against CPUSA members, and that less than half of those convicted ever went to jail (with those who did receiving brief sentences). 95

A more lasting government attack on the CPUSA was conducted by state insurance regulators who forced the liquidation of low-cost insurance programs run by the International Workers Order, a CPUSA affiliate. The insurance products had been providing the party an important revenue stream. 96

The U.S. Congress launched several famous investigations into communism during this era. However, according to Klehr and Haynes, “much of the history of the Communist controversy in Washington during the 1950s was only indirectly connected to the history of the [Communist Party USA].” In 1950, U.S. Sen. Joseph McCarthy (R-Wisconsin) launched a controversial and often reckless investigation alleging communist infiltration of the U.S. Army, the U.S. State Department and the highest reaches of the U.S. government. Also, in the early 1950s, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and the Senate Internal Security Committee investigated communist influence over labor unions, Hollywood, government, and other corners of American life. The HUAC investigation revealed U.S. State Department officials had spied for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. 97

By 1954 the peak of the brief post-war passion for suppressing the CPUSA had passed. The end of the Korean War, the Marshall Plan’s ongoing success in rebuilding the economies of Western Europe, and prosperity at home all lowered the Cold War anxiety Americans had built up regarding their future and the Soviet Union. The reckless accusations of Sen. McCarthy were being challenged by Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who took office in 1953. McCarthy was censured by the U.S. Senate in December 1954 and largely stripped of his power to continue his crusade against communism. 98

Khrushchev Denounces Stalin

Soviet communist leader Joseph Stalin died in March 1953. He was replaced shortly thereafter by Nikita Khrushchev, who replaced his predecessor’s hard line foreign policy with a less antagonistic “peaceful coexistence” policy. Among other reforms this included ending the Soviet Union’s hostility toward the independent communist government of Yugoslavia. Then in February 1956, while speaking in what he intended to be a secret address to the Communist Party leadership of the Soviet Union, Khrushchev denounced the purges, killings and “cult of personality” imposed by Stalin. When the U.S. government obtained a copy of the Khrushchev address and released it in June 1956, it unleashed another major blow to the remaining membership of the Communist Party USA. 99

Though the Stalin-era atrocities had already been widely reported, most in the CPUSA had refused to believe in them until Khrushchev acknowledged the truth. “Once Khrushchev gave Moscow’s sanction to the charges against Stalinism,” wrote Klehr and Haynes, “American Communists, in shock, suddenly saw bodies littering the landscape.” 100

The Daily Worker, the CPUSA’s newspaper, published the speech in full. After reading it the wife of CPUSA general secretary Eugene Dennis wrote that she cried for “a thirty-year life’s commitment that lay shattered.” She was typical of many – in the aftermath of the Khrushchev revelations the CPUSA newspapers filled up with letters and essays from a betrayed and angry movement. 101

Daily Worker editor John Gates, a CPUSA loyalist who had recently been convicted of and served time for Smith Act violations, led a minority faction within the party promoting reforms that would steer the party toward an “American road to socialism” that was longer reliant on the Soviet Union’s interests. Gates’ reforms were opposed by CPUSA general secretary William Z. Foster, and soon also by Pravda, the Soviet Union’s state-run newspaper. 102

Hungarians responded to Khrushchev’s speech by ejecting their Stalinist-era communist leadership and pursing independence from the Soviet-controlled Warsaw Pact, effectively moving to break out from behind the Iron Curtain. The Soviet Union responded in November 1956 with a violent military crackdown that killed thousands of Hungarian reformers and placed a new Soviet-controlled puppet in charge of the nation. The CPUSA faction represented by Gates denounced the Soviet assault on Hungary, while Foster and his faction endorsed it. 103

The CPUSA members most dismayed by the official Soviet revelations regarding Stalin steadily left the party, leaving a greater concentration of Foster-aligned hardliners remaining to fend off fewer and fewer Gates-aligned reformers. Gates gave up, resigned from the CPUSA in January 1958, and was then officially denounced the next month at the party convention. This accelerated the departure of reformers from the CPUSA. The official report of CPUSA membership in 1958 was just 3,000 – down more than 75 percent from two years earlier. 104

Late Cold War: 1960-1991

In 1959 Eugene Dennis was replaced as leader of the Communist Party USA by Gus Hall. Hall would hold the CPUSA leadership until his death in October 2000, a run spanning the last three decades of the existence of both the Soviet Union and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and then almost a decade beyond. Hall was (until the end of the Soviet Union itself) a reliable supporter of the policies of every one of its leaders, with his favorite reportedly being Leonid Brezhnev. 105 Soviet archives unveiled after the Cold War revealed that between 1971 and 1990 Hall and the CPUSA had received subsidies of $40 million from the Soviets. 106

New Left Era

The tiny Communist Party USA that existed in the early years of the 1960s was up against what historians Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes characterized as a “comfortable America” where radical politics “seemed irrelevant.” By the middle of the decade and into the 1970s a much more radical left would emerge, but the CPUSA, being “old, tired and increasingly out-of-step with American life,” would remain poorly positioned to take advantage of it. Speaking of Hall’s leadership, Klehr and Haynes report the CPUSA “barely profited from the largest upsurge of American radicalism since the Great Depression.” 107

The civil rights movement, black nationalism, opposition to the Vietnam War, and other political causes energized the left in the United States beginning in the mid-1960s. But along with this trend, according to Klehr and Haynes, American radicals had lost their attraction for the Soviet Union, which they now viewed as a “stodgy, status quo power.” Upstart communist revolutionaries and movements in nations such as China, Cuba and Vietnam were the new models to idolize and emulate for many in America’s New Left, and a CPUSA deeply tied to the Soviets did not profit in this environment. 108

Dozens of organizations, some democratically inclined and some violent, emerged instead, including Students for a Democratic Society, the Black Panther Party, the Weather Underground, the Progressive Labor Movement, and the Socialist Workers Party. Briefly and mildly successful, the Socialist Workers Party would grow strong enough to obtain 91,000 votes for its 1976 U.S. Presidential ticket – placing only eighth in the popular vote, but still more than 32,000 votes ahead of the ninth-place CPUSA ticket headed by Gus Hall. 109

The CPUSA, as one of many participants in a sometimes ideologically diverse coalition that encompassed more than just the ideological left, did participate in the organizations that created the biggest demonstrations against the Vietnam War. And within the anti-war coalitions, the CPUSA often occupied a lonely and more moderate ideological position. Where the CPUSA once advocated negotiations between the United States and North Vietnam to resolve the conflict (an outcome desired by the Soviet Union), the Socialist Workers Party and others on the New Left demanded an immediate withdrawal of American forces from South Vietnam. 110

The level of impact the CPUSA had in these movements is another matter. Even through the mid-1970s, CPUSA membership remained less than 10,000. And even with membership briefly reaching as high as 15,000 in the 1980s, CPUSA leaders were still complaining their small support base placed “limitations on what we can do or contribute.” The party had “limped through the turbulent 1960s,” according to Klehr and Haynes, advocating “alliances with liberal Democrats” and “peaceful coexistence with the Soviet Union.” But, the CPUSA had survived the decade, while nearly all the New Left organizations had burned out as a result of their tactics, violence, extreme ideology and factional infighting. 111

The “End of Communism”

After the expiration of most of the New Left, Communist Party USA policy, tactics and effectiveness remained mostly unchanged from the mid-1970s up through the collapse of the Soviet Union. Moving in the direction of its alliances with liberal Democrats, the CPUSA ran its last independent presidential candidate (Gus Hall, for the fourth time) in 1984, and in 1988 moved instead to support left-leaning Democratic candidates. CPUSA members and allies were supporters of and active in the presidential campaign of Democrat Jesse Jackson and his Rainbow Coalition. 112

In 1991, after the Berlin Wall had collapsed and began to take Soviet Communism down with it, Gus Hall denounced Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev for abandoning the Soviet Union to capitalists and refused to accept that the people of Eastern Europe had turned against communism. 113 In early 1990, he accused the East Germans who were fleeing west across the toppled Berlin Wall of seeking “gadget socialism” and wanting “videotapes, microwave ovens, computers, all kinds of gadgets.” Hall predicted East Germans would change their minds. 114

Then at a 1991 news conference in Manhattan, he told reporters he was looking to a more reliable model of communist success to replace the Soviet Union. “The world should see what North Korea has done,” he said. “In some ways it’s a miracle. If you want to take a nice vacation, take it in North Korea.” 115

Post-Cold War CPUSA

Gus Hall died in October 2000. A 1989 U.S. State Department report estimated the size of the CPUSA at no more than 5,000 members. 116 His final years in charge of the Communist Party USA coincided with the first years of the CPUSA untethered to the needs of the Soviet Union, but Hall continued to lead the party as if little had changed: “Even political associates sometimes found Mr. Hall’s obeisance to the Soviet Union excessive,” reported the New York Times obituary, “and they grumbled, especially in his later years, that his inflexible views and dictatorial personality were hampering the party and isolating it from the wider political world.” 117

As of April 2017, the CPUSA claimed 5,000 members. 118 Independent estimates have generally asserted much lower membership totals than the CPUSA has claimed. 119 As of 2014, the CPUSA had two salaried employees working out of a New York City office. 120

The modern CPUSA engages in mostly conventional advocacy of left-wing policy and politics.

“The positions they take are really indistinguishable from the left-wing social democratic groups,” said historian Ron Radosh to the BBC in 2014. “I don’t even know why anyone belongs to it.” Historian Harvey Klehr told the same interviewer the CPUSA had become “a sect, a cult almost,” and that he had stopped paying attention to it in the early 2000s because it had become “essentially irrelevant.” 121

Spying for the Soviet Union

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and its communist party, the newly constituted non-communist Russian government briefly opened access to some previously secret information regarding the Soviet Union’s espionage history. These documents, information released by a KGB defector, and counter-espionage documents declassified by the U.S. government (the “Venona” project) revealed an extensive history of high-level officials from the Communist Party USA helping Soviet espionage agencies work against the United States. Just the scope of the spying shown by the American-produced Venona reports reveals the involvement of hundreds of people from the CPUSA, beginning in the late 1920s and continuing into the early Cold War. 122

The revelations provided by these sources forced American historians to seriously alter their assessment of the CPUSA’s cooperation with Soviet espionage efforts. Historians John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr were some of the first to review both the Soviet archives and Venona information. Having written in the early 1990s that espionage “was not a regular activity” of the CPUSA, the new facts revealed shortly thereafter led them to undergo what they said in 2006 was a “serious revision.” In their 1999 book about the Venona documents, they conclude “the CPUSA was indeed a fifth column working inside and against the United States in the Cold War.” Maurice Isserman, another historian cited by Haynes and Klehr, wrote in 1999 that it was “abundantly clear that the Soviet Union recruited most of its spies in the United States in the years leading up to and during World War II from the ranks of the Communist Party or among its close sympathizers — an effort in which top party leaders were intimately involved.” 123

The CPUSA was implicated in such activities as recruiting potential spies and sources, running background checks on individuals the Soviets were targeting as potential sources, providing safe houses and forged passports, and creating businesses and jobs to provide cover stories for Soviet spies. 124

The most senior CPUSA person implicated was Earl Browder, a high-ranking CPUSA officer for most of the years of CPUSA cooperation with Soviet espionage agencies, and the top leader (chairman) of the CPUSA from 1934-1945. A KGB memo from 1946 credits Browder with recruiting 18 agents for that Soviet espionage agency, and others for the GRU, the Soviet Union’s military intelligence branch. 125

Another KGB document from 1942 represents a note from Eugene Dennis to the KGB, discussing the placing of CPUSA members into the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the World War II precursor to the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. Dennis was then the second in command to Browder at the CPUSA and would later replace Browder as the CPUSA general secretary. Separately and many years earlier Dennis had been implicated in placing communists within the OSS by Louis Budenz, another CPUSA member who had spied for the Soviets and then in the late 1940s became an FBI informant. 126

“Earl Browder, Eugene Dennis and other senior CPUSA officials,” wrote Klehr and Haynes in 2006, “were not only aware of cooperation with Soviet intelligence but supervised it, promoted it, and ordered subordinate party officers to assist.” 127

References

- Lewis, Aidan. “The curious survival of the US Communist Party.” BBC. May 1, 2014. Accessed August 14, 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-26126325

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Haynes, John Earl; and Harvey Klehr. “The Historiography of Soviet Espionage and American Communism: from Separate to Converging Paths.” “International Communism and Espionage” session, European Social Science History Conference. March 2006. Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Accessed August 15, 2019. http://www.johnearlhaynes.org/page101.html

- Tanenhous, Sam. “Gus Hall, Unreconstructed American Communist of 7 Decades, Dies at 90.” The New York Times. October 17, 2000. Accessed August 14, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2000/10/17/us/gus-hall-unreconstructed-american-communist-of-7-decades-dies-at-90.html

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Kenez, Peter. “80th Anniversary of a Poisonous Partnership: Hitler and Stalin.” Law & Liberty. August 05, 2019. Accessed August 16, 2019. https://www.lawliberty.org/liberty-forum/80th-anniversary-of-a-poisonous-partnership-hitler-and-stalin/.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Lewy, Guenter. The Cause that Failed: Communism in American Political Life. New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1990.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- “Control of Communism in the United States.” CQ Researcher by CQ Press. February 11, 1948. Accessed April 22, 2019. https://library.cqpress.com/cqresearcher/document.php?id=cqresrre1948021100.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.

- Klehr, Harvey; and John Earl Haynes. The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself. New York: Twayne Publishers. 1992.