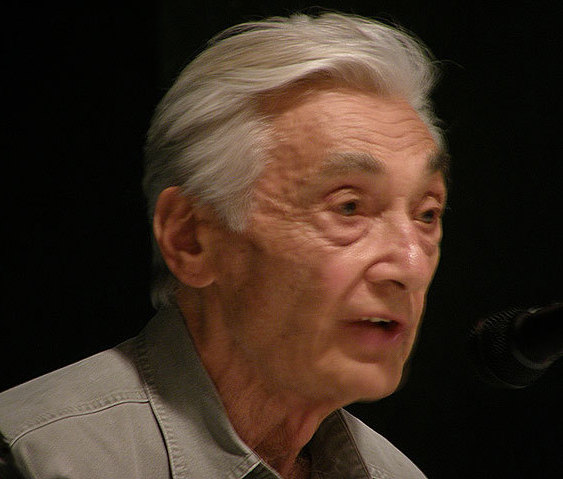

Howard Zinn was a professor of history at Boston University and a left-wing political activist who described himself as “something of an anarchist, something of a socialist” and “maybe a democratic socialist.” 1 He was a supporter of many so-called “New Left” causes, such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Black Panther party, and more conventional “old left” causes such as the Maoist Progressive Labor Party. 2 Zinn sympathized with the Communist Viet Cong’s effort to overthrow the government of South Vietnam, and was repeatedly an opponent of the use of military force by the United States. 3 In 2003 he stated that the attacks of September 11, 2001, were being used “as a way to cover up the failure to solve domestic problems and build support for a President who got into office through a political coup and needs to show he has a mandate he doesn’t deserve.” 4 Zinn died in 2010.

Zinn repeatedly denied having ever been a member of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA), even though during his lifetime a book by two Kent State University historians stated Zinn had been “an active party member for almost a decade.” 5 After his death the FBI released a file providing accounts from various informants who claimed Zinn was a CPUSA member as far back as the late 1940s. 6 The FBI informants reported Zinn had been in a leadership position with one known CPUSA front organization, a member of many others, and was known to have been a CPUSA member as far back as 1949. 7 Another informant report recounted a 1948 protest at the White House in which Zinn stated he was a CPUSA member. 8 An FBI photograph of Zinn dated 1951 was identified as showing him teaching an introductory Marxism class at the CPUSA local headquarters for Brooklyn, New York. 9 One of his former neighbors also told the FBI she believed Zinn to be a communist. 10

Zinn is best known for writing A People’s History of the United States, first published in 1980 and the subject of strong sales and harsh criticisms ever since. 11 In a 2012 poll of readers of the History News Network, the book finished in second place as the least credible history book in print. 12 Writing in Dissent, a left-of-center opinion journal, Georgetown University professor Michael Kazin judged the book to be “bad history” and said Zinn was an “evangelist of little imagination” who ignored both the “errors of judgement” by the modern left and the “Communist Party’s lockstep praise of Stalin.” 13 14 Speaking about the Cold War in 2012, Emory University historian Harvey Klehr wrote that “decades of deeply dishonest books by such popular historians as Howard Zinn have contributed to Americans’ moral amnesia about the defeat of the second totalitarian enemy of liberal democracy in the 20th century.” 15

Historians have challenged the book’s facts and misrepresentations on numerous fronts, such as his descriptions of the involvement of African Americans in World War II, the level of spying by American communists against the United States during the Cold War, and the severity of Allied strategic bombing during World War II. 16 Stanford University professor Sam Wineburg wrote that A People’s History “places Jim Crow and the Holocaust on the same footing, without explaining that as color barriers were being dismantled in the United States, the bricks were being laid for the crematoria at Auschwitz.” 17 Describing the intent of the book, Zinn said he was seeking a “quiet revolution” from “the bottom up” that produced “democratic socialism” in the United States that would rival the “German and the French and the Scandinavian models.” 18

Background

Howard Zinn was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1922. By his late teens, according to biographer Martin Duberman, he was an avid reader of Marxism and politics. He served in bomber squadrons in Europe during World War II, and after the war earned a Ph.D. in history from Columbia University. In 1956 Zinn was hired to chair the history and social sciences department at Spelman College, a single-sex college for African American women in Atlanta, Georgia. 19

Zinn became active with the civil rights movement during the era. He was the academic advisor to Spelman’s chapter of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), an organization then involved in sit-ins and other acts of non-violent civil disobedience in defiance of segregation laws and traditions. He remained close with the SNCC after it appointed as its leader the militant Marxist Stokely Carmichael and veered away from its alliances with mainstream civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr. 20

The Southern Mystique, one of the first of the 20-plus books Zinn wrote throughout his life, was his 1964 analysis of the civil rights movement. Writing about Zinn for The New Republic in 2013, Rutgers University historian David Greenberg said several knowledgeable writers and scholars of the era who were otherwise sympathetic to the civil rights cause found The Southern Mystique to be “shallow and mystifyingly detached from any discussion of the South’s unique historical experiences.” 21

Greenberg, reviewing a biography of Zinn for The New Republic, also wrote that Zinn’s contributions as a researcher and historical scholar were thin: his “thoughts on scholarship appear jejune” and he “comes across as a lazy, conventional theorist.” 22

The Ph.D. dissertation Zinn wrote while a student at Columbia, was “well received,” continued to be cited by scholars for decades afterward, and was the basis for Zinn’s employment offer from Spelman College, according to Greenberg. But that mid-1950s doctoral work was also the “only sustained engagement with archival documents” of Zinn’s career. While Zinn was engaged in activism, Greenberg reports “many of his peers in the historical profession were throwing themselves into scholarship” and “contributing to the “intellectual ferment” of “seminar rooms, journal offices, and conferences.” 23

Spelman College president Albert Manley fired Zinn in 1963 for reasons that remain in dispute.

Zinn’s account was that his participation in demonstrations with and encouragement of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee had upset Manley (who was African American) and led to the termination. “I was fired for insubordination,” said Zinn. “Which happened to be true.” 24

David Greenberg, citing Zinn’s biographer, stated Manley’s justification for the firing as being “ostensibly on scholarly grounds.” Zinn responded by enlisting the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) to help get him reinstated. According to Greenberg’s book review, this is what occurred next: 25

In the negotiations, Manley threatened to publicize an old incident in which local police found Zinn and a Spelman student alone in his car at night at the end of a cul-de-sac. Zinn insisted that nothing sexual had occurred, but he still did not want his wife, who was prone to depression, to find out. What really happened? Duberman [Zinn’s biographer] says there is no way to know. Manley refused to yield, and the AAUP dropped the case. 26

After departing from Spelman, Zinn took a position as a history professor at Boston University in 1964, where he remained until his retirement from teaching in 1988. According to Zinn’s 2010 obituary in the New York Times: 27

He waged a war of attrition with Boston University’s president at the time, John Silber, a political conservative. Mr. Zinn twice organized faculty votes to oust Mr. Silber, and Mr. Silber returned the favor, saying the professor was a sterling example of those who would “poison the well of academe.” 28

According to Greenberg, the 1980 publication of Zinn’s most famous book, A People’s History of the United States, provided him financial independence from his university job and thus “liberated him from Silber’s fist.” 29

Zinn was repeatedly an opponent of the use of military force by the United States. In a 2003 interview he said the United States was using the attacks of September 11, 2001, as an excuse to “bomb” Afghanistan and Iraq, “as a way to cover up the failure to solve domestic problems and build support for a President who got into office through a political coup and needs to show he has a mandate he doesn’t deserve,” and as a pretext “to expand American power in the Middle East.” 30 In 1970, Zinn and radical left wing activist Noam Chomsky began to assist in editing and publishing the Pentagon Papers—the U.S. government’s then-classified investigation into the history of the Vietnam War. 31 During the Vietnam War Zinn agreed with the objectives of the National Liberation Front (known to the American public as the “Viet Cong”), the guerilla army trying to overthrow the government of South Vietnam and subordinate it to the leadership of communist North Vietnam. 32

Asked to describe his ideology in 2003, Zinn replied: “Something of an anarchist, something of a socialist. Maybe a democratic socialist.” 33

Communist Party Allegations

In the summer of 2010, following Zinn’s death earlier that year, the FBI released a 423-page file it had compiled on Zinn, beginning in 1949 when the Bureau first began suspecting Zinn of involvement with the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Throughout his life, Zinn had denied ever being a member of the CPUSA. 34

Shortly after the release, historian Ronald Radosh wrote an essay for the Weekly Standard, concluding: “Zinn was an active member of the Communist party (CPUSA)—a membership which he never acknowledged and when asked, denied.” 35

Radosh himself was a former CPUSA member and noted that the FBI’s file on him from those days was 500 pages long. Citing his personal and professional experience with the files and the CPUSA, he said the Bureau reports were generally accurate, with “exaggerations or gross mistakes” occurring only “when agents venture their own analyses or summaries, since these reflect their limited knowledge of American Communism.” But addressing the evidence presented against Zinn in the reports, Radosh said “when an informant offers a straight report about what he or she saw as a result of infiltrating (or belonging to) a Communist organization, it is usually accurate.” 36

For Radosh the “most damning” evidence implicating Zinn was a 1957 informant report from a CPUSA member to the FBI, telling the Bureau that he (the CPUSA informant) had been transferred to a new CPUSA branch in 1949, whereupon the informant discovered Zinn was “already a member of that section,” had “been in the CP for some time” and “as a general rule was always present when meetings took place.” 37

And Radosh quotes an informant who took part in a 1948 White House protest, told the Bureau Zinn was there as well, and said that during the event Zinn claimed “that he is a member of the Communist Party and that he attends Party meetings five times a week in Brooklyn.” 38

Radosh reported that Zinn denied CPUSA membership when the FBI asked him in 1953, but that investigators were not fooled because of Zinn’s collaboration with many CPUSA-affiliated organizations. Radosh states “there was virtually no front group to which Zinn did not belong,” and listed as examples “the ALP [American Labor Party], the American Veterans Committee, the American Peace Mobilization, the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee, and many, many others.” The FBI began investigating Zinn in 1949 when he was vice-chairman of the Brooklyn brand of the ALP, which Radosh wrote was “by then a group run and dominated by Communists.” 39

Radosh concluded Zinn’s files fit the pattern of a willing and active CPUSA member:

Some would claim that Zinn might have been an idealistic, left-wing activist, eager to join the campaign of many single issue groups. This, however, is more than doubtful. By those years, most people joining these pro-Soviet groups were Communists. To those familiar with how American Communists operated, his memberships appear to be a party assignment. 40

Daniel J. Flynn, a writer for the Manhattan Institute’s City Journal, made similar observations in his August 2010 essay examining Zinn’s FBI file, and provided additional anecdotes. 41

Flynn quoted the FBI files referencing “a photograph of Zinn taken in about 1951 which showed him instructing a class in Basic Marxism at the Twelfth Assembly District, CP Headquarters, Brooklyn, New York.” After noting Zinn had told FBI agents that he was a liberal, but not a communist, Flynn asked: “Were Stalin-era Communists in the habit of inviting “liberals” to teach them about Marxism?” 42

“The Zinn that emerges from the files manned picket lines, religiously attended almost daily party meetings, and collected subscriptions for The Daily Worker [the official CPUSA newspaper],” wrote Flynn of the FBI file. “His work on behalf of radical causes was apparently so conspicuous that even a neighbor told the FBI that she believed Zinn was a Communist.” 43

Speaking of Zinn and the CPUSA in their book Black History and the Historical Profession, 1915-1980, Kent State University history professors August Meier and Elliott Rudwick reported Zinn was “an active party member for almost a decade.” 44

Radosh wrote that Zinn also left the CPUSA, but to form allegiances on the more radical left:

Zinn had clearly left the party’s ranks by the time the New Left and the civil rights movement came on the scene. Indeed, his politics were to the left of the party. The CP supported “Negotiations Now” as a way out of Vietnam; Zinn proposed unilateral withdrawal. To be sure, he supported Third World Marxist regimes like Vietnam and Cuba. He toyed with radical groups at home such as the Maoist Progressive Labor party and the Trotskyist Socialist Workers party. He also gave his support to the young black militants of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Black Panther party. 45

A People’s History of the United States

Zinn’s most famous book is A People’s History of the United States, first released in 1980. The book was updated and reprinted several times from then until Zinn’s death in 2010, eventually earning him annual royalties of $200,000 and (as of 2013) selling in excess of two million copies. 46 Commenting on its popularity in 2003 the Chronicle of Higher Education reported it “continues to be assigned in countless college and high-school courses, but its commercial sales have remained strong as well.” 47

The list price for the first 1980 edition was $20 ($62 in 2019 dollars). 48

In a 2012 poll of readers of the History News Network, the book finished in second place as the least credible history book in print. 49

Reviewing a 2012 biography of Zinn for The New Republic, Rutgers University professor of journalism and history David Greenberg wrote that A People’s History was Zinn’s effort to give the “American experience as seen by the losers and the victims.” Or, as he quoted Zinn: “the discovery of America from the viewpoint of the Arawaks, of the Constitution from the standpoint of the slaves, of Andrew Jackson as seen by the Cherokees, of the Civil War as seen by the New York Irish … the Gilded Age as seen by southern farmers, the First World War as seen by socialists, the Second World War as seen by pacifists, the New Deal as seen by blacks in Harlem, the postwar American empire as seen by peons in Latin America.” 50

Greenberg wrote that “Zinn was in effect saying that Big-Time History—with its formidable air of authority, its footnotes and archival documentation, its vetting by communities of expert scholars—had really just served to shore up the power of established elites and put down stirrings of protest.” So, in writing A People’s History, Greenberg said Zinn had “abjured any pretense of having written a comprehensive or balanced account” and “stated plainly that he meant to take sides” against the so-called “established elites.” 51

In his 2012 biography of Zinn, left-leaning historian Martin Duberman wrote that the “overriding theme” of A People’s History “is that the American experience from start to finish has essentially been the story of how the powerful few have deceived and dominated the many.” 52

“Sometimes A People’s History lacks nuance,” wrote Duberman, “with the world divided into oppressors and oppressed, villains or heroes; the history of the U.S. is treated as mainly the story of relentless exploitation and deceit. Demonic elites are often presented as repressing the helpless masses, even robbing them of cultural vitality.” 53

Describing the intent of the book to Georgia’s Flagpole magazine in 1998, Zinn said he was seeking a “quiet revolution” from “the bottom up” that produced “democratic socialism” in the United States that would rival the “German and the French and the Scandinavian models.” 54

The Zinn Education Project was created to encourage the use of A People’s History and its online resources related to same by K-12 and other history instructors. As of October 2019, the Zinn Education Project claimed 80,000 instructors had signed up to use the materials, with 10,000 more doing so every year. 55

Scholarly Critics

Historians judging A People’s History have generally criticized both the scholarship and the selective use of facts. In his 2013 essay in The New Republic regarding the life of Zinn, Rutgers University professor David Greenberg stated the book was “a pretty lousy piece of work” and that most of the first reviews of it from other historians “were not kind.” 56

In his own analysis of the legacy of the book, Greenberg wrote that it was “distressingly easy today to find tendentious scholarship that exhibits a Zinn-like habit of judging historical acts and actors by their contemporary utility.” And while nothing that “excellent work is done by self-identified leftists” Greenberg said the Zinn school of historical analysis is shown when “too much academic work today assumes such dubious premises as (to name but a few) the superiority of socialism to a mixed economy, the inherent malignancy of American intervention abroad, and the signal virtue of the left itself.” 57

Many other prominent historians, including more than one with a left-of-center ideological orientation, have been sharply critical of A People’s History.

Michael Kazin

Michael Kazin is a history professor at Georgetown University and the editor of Dissent, a left-leaning opinion journal. 58 In an essay written for the Spring 2004 issue of Dissent, Kazin concluded the book was “bad history” that had been “gilded with good intentions,” and that Zinn was an “evangelist of little imagination for whom history is one long chain of stark moral dualities.” 59

Speaking generally of the book’s flaws and ideological bias, Kazin wrote: “By Zinn’s account, the modern left made no errors of judgment, rhetoric, or strategy. He never mentions the Communist Party’s lockstep praise of Stalin or the New Left’s fantasy of guerilla warfare.” 60

Sean Wilentz

Sean Wilentz is a professor of American history at Princeton University. He has been an outspoken supporter of left-of-center politicians—he endorsed then-U.S. Senator Hillary Clinton (D-NY) for president in 2008—and opponent of Republicans, having written a 2006 essay for Rolling Stone arguing former President George W. Bush was potentially the worst President in American history. 61 62

Following Zinn’s death in 2010, the Los Angeles Times asked several historians to analyze Zinn’s contributions to the field. “He saw history primarily as a means to motivate people to political action that he found admirable,” said Wilentz. “It’s fine as a form of agitation — agitprop — but it’s not particularly good history.” 63

Wilentz concluded with the following:

He had a very simplified view that everyone who was President was always a stinker and every left-winger was always great. That can’t be true. A lot of people on the left spent their lives apologizing for one of the worst mass-murdering regimes of the 20th century, and Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves. You wouldn’t know that from Howard Zinn. 64

Harvey Klehr

Harvey Klehr is professor of politics and history at Emory University and an expert on the history of left wing and communist politics in the United States. Along with his research partner, he was one of the first to analyze post-Cold War Soviet archives that proved the depth of the espionage undertaken for the Soviet Union against the United States by members of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). 65

In a November 2012 magazine essay analyzing how Americans remember the Cold War and the Soviet Union, Klehr wrote that “decades of deeply dishonest books by such popular historians as Howard Zinn have contributed to Americans’ moral amnesia about the defeat of the second totalitarian enemy of liberal democracy in the 20th century.” 66

Oscar Handlin

The late Oscar Handlin was a Pulitzer Prize winning professor of history at Harvard University. In 1980, writing in the academic journal American Scholar, he was one of the first historians to publish a review of the first edition of A People’s History. 67

Handlin was exceptionally brutal in his criticism. He stated that the “book pays only casual regard to factual accuracy” and that a “careful reader will perceive that Zinn is a stranger to evidence bearing upon the peoples about whom he purports to write.” The Harvard professor said A People’s History was a “fairy tale” with a “deranged quality” where “the incidents are made to fit the legend, no matter how intractable the evidence of American history.” Of the book’s style, Handlin said it “conveniently omits whatever does not fit its overriding thesis” and that “only critics who know the sources will recognize the complex array of devices that pervert his pages.” 68

Wilfred McClay

Wilfred McClay is a professor of history at the University of Oklahoma. In a May 2019 interview with the Wall Street Journal about a forthcoming book of his own, McClay criticized Zinn for “greatly oversimplifying the past and turning American history into a comic-book melodrama in which ‘the people’ are constantly being abused by ‘the rulers.’” McClay also judged the popularity of Zinn as indicative of a failure in field if historical writing: “Just as nature abhors a vacuum, so a culture will find some kind of grand narrative of itself to feed upon, even a poisonous one.” 69

“Zinn’s success is indicative of our failure,” said McClay. “We have to do better.” 70

Ronald Radosh

Ronald Radosh is a former professor of history at City University of New York. 71 He is also a former member of the Communist Party USA who later broke with the left to become a right-of-center writer. 72

Radosh has been an outspoken critic of The Politically Incorrect Guide to American History, a 2005 book written from a right-of-center perspective by Thomas Woods, Jr. Radosh wrote a 2005 essay posted by the History News Network titled “Why Conservatives Are So Upset with Thomas Woods’s Politically Incorrect History Book,” in which he called Woods’ work a “specious far-right assault on the truth” that is a “propagandastic, cartoon-like portrait of the United States.” Radosh equated The Politically Incorrect Guide with Zinn’s A People’s History (what he called a “deeply flawed history”), and concluded: “ I would suggest that it is the success and influence of such skewered left-wing versions of the American story as that by Howard Zinn that has opened the door for a similar crude response from the quarters of the paleoconservative Old Right.” 73

Factual Errors and Omissions

Critics of A People’s History have also cited numerous specific examples of Zinn’s misrepresentation of—and failure to include—relevant historical facts. Several instances were pointed out in “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short,” a 2012 analysis written by Stanford University professor Sam Wineburg for the trade magazine of the American Federation of Teachers, a left-of-center public school employee union. 74

African Americans and World War II

Sam Wineburg challenged the assertion made in A People’s History that racism in the United States led to African Americans having “widespread indifference, even hostility” toward helping the nation win World War II. Wineburg traced Zinn’s evidence for this claim to three anecdotes from three individuals cited in a single source, a book written in 1969. 75

Examining the same book, Wineburg revealed Zinn had omitted highly significant facts and inverted the author’s point. Rather than portray African Americans as opposed to fighting, Zinn’s source had included the anecdotes to demonstrate exceptions to the general truth that African Americans were instead exceptionally patriotic. The omitted facts from the book show African Americans comprising 24 percent of the draft-eligible men during the era yet contributing just 4.4 percent of draft resisters and less than one percent of total conscientious objectors. 76

Generally denouncing Zinn for misrepresenting the conflict and portraying the American and Nazi systems as equally evil, Wineburg said that A People’s History places Jim Crow and the Holocaust on the same footing, without explaining that as color barriers were being dismantled in the United States, the bricks were being laid for the crematoria at Auschwitz.” 77

Citing David Irving Regarding the Bombing of Dresden

Wineburg also exposes both deceptive omissions and discredited sources used to support assertions made in A People’s History regarding the American and British firebombing of the German city of Dresden.

Purporting to demonstrate moral equivalence between the conduct of the Nazis and the violence inflicted by the Americans and British, Zinn’s account compares the Allied assault against Dresden—which took place in February 1945—to the Nazi bombings of Coventry (in Britain) and Rotterdam (in Holland), both of which occurred in 1940. Zinn wrote that the total killed by the Nazis in Coventry and Rotterdam (less than 1600) paled in comparison to the tens of thousands killed by the Allies in Dresden alone. 78

In the first of three challenges to the facts used in A People’s History, Wineburg accused Zinn of selectively choosing his dates. Wineburg clarified that violence against civilian targets was lower earlier in the War, when the Coventry and Rotterdam attacks occurred. At a comparable point to the Rotterdam and Coventry raids, Wineburg notes that British Royal Air Force pilots were “restricted to dropping propaganda leaflets over Germany and trying, ineffectually, to disable the German fleet docked at Wilhelmshaven.” Wineburg contrasted this with the behavior of both sides five years later in 1945, when “all bets were off and long-standing distinctions between military targets (“strategic bombing”) and civilian targets (“saturation bombing”) had been rendered irrelevant.” 79

Wineburg’s second criticism accused Zinn of ignoring the September 1939 Nazi firebombing of Warsaw during the opening weeks of World War II in Europe, an attack that took place well before the tamer Nazi attacks on Coventry and Rotterdam and more than five years before Dresden. Wineburg noted this assault on a civilian target killed 40,000 Poles and turned the town into a fire that could be seen from 70 miles away. Of the coverage of this incident in A People’s History, Wineburg wrote: “Zinn is silent about Poland.” 80

Wineburg’s third challenge to Zinn’s facts occurred in a footnote to the essay. A People’s History cited the death toll from Dresden at in excess of 100,000, but Wineburg stated more credible estimates of 20,000 to 30,000. Wineburg noted in the footnote that Zinn’s source was The Destruction of Dresden, a 1965 book written by David Irving and based on “mortality figures provided by the Nazis for propagandistic purposes.” Alluding to Irving’s later exposure as a non-credible historian and a Holocaust denier, Wineburg wrote: “On David Irving’s mendacity, see Richard J. Evans, Lying about Hitler: History, Holocaust, and the David Irving Trial (New York: Basic Books, 2002).” 81

Spying by American Communists

Chapter 16 of A People’s History covered World War II and the early Cold War era. It included information about the reckless allegations made by former U.S. Senator Joe McCarthy (R-WI) during poorly evidenced attempts to expose infiltration of the U.S. government by Soviet communist spies. 82

But unlike most histories, which separated the misdeeds of McCarthy from the work of more careful politicians investigating allegations of Soviet espionage, Zinn portrayed mainstream political figures from both parties as being complicit in so-called “McCarthyism.” According to A People’s History: “It was not McCarthy and the Republicans, but the liberal Democratic Truman administration, whose Justice Department initiated a series of prosecutions that intensified the nation’s anti-Communist mood.” 83

Following the demise of the Soviet Union, the successor non-communist government of Russia briefly provided access to archives of the KGB for inspection by historians. Along with evidence provided by a KGB defector and the FBI’s declassification of one of its most successful Cold War counterespionage programs (the “Venona” project), the Soviet data revealed top members of the Communist Party USA to have been participants in Soviet espionage against the United States. In a 1999 book about their research into these sources, historians Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes concluded “the CPUSA was indeed a fifth column working inside and against the United States in the Cold War.” 84

Following Zinn’s death, Sheldon M. Stern, former historian at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, wrote an essay for the History News Network in which he argued “Zinn’s legacy as a historian is very much in dispute.” One of the anecdotes Stern told in support of this point touched on the revelations about American communists and Soviet espionage:85

On one occasion I spoke to him about new documents available on the website of the Cold War International History Project, especially the crucial material from the archives of the former Soviet Union. He was courteous, if not avuncular, but did not seem particularly interested in them or knowledgeable about them. I asked him specifically about the groundbreaking scholarship of John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr; he replied that we should be wary of any work that appears to justify the repression of the McCarthy era and prop up the “established narrative” of the Cold War. I noted that McCarthy did not even know about the U.S. government’s “Venona” intercepts, which exposed domestic espionage by Soviet and American communists; Zinn countered incongruously that the capitalists now running Russia would go to any lengths to cozy up to the power brokers of American capitalism. 86

The conviction and execution of Soviet spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg is a specific area where historians have accused Zinn of putting his ideology in place of scholarship. In his 2013 essay Stanford professor Sam Wineburg wrote:87

A People’s History devotes nearly two and a half pages to the case, casting doubt on the legitimacy of the Rosenbergs’ convictions as well as that of their accomplice, Morton Sobell. Sobell escaped the electric chair but served 19 years in Alcatraz and other federal prisons, maintaining innocence the entire time. However, in September 2008, Sobell, age 91, admitted to a New York Times reporter that he had indeed been a Russian spy, implicating his fellow defendant Julius Rosenberg as well. Three days later, in the wake of Sobell’s admission, the Rosenbergs’ two sons also concluded with regret that their father had been a spy. Yet, when the same New York Times reporter contacted Zinn for a reaction, he was only “mildly surprised,” adding, “To me it didn’t matter whether they were guilty or not. The most important thing was they did not get a fair trial in the atmosphere of cold war hysteria.” 88

References

- Glavin, Paul; and Chuck Morse. “War is the Health of the State.” HowardZinn.org. March 22, 2003. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://www.howardzinn.org/war-is-the-health-of-the-state/

- Radosh, Ronald. “Aside from That, He Was Also a Red.” The Weekly Standard. August 16, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/aside-from-that-he-was-also-a-red

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Glavin, Paul; and Chuck Morse. “War is the Health of the State.” HowardZinn.org. March 22, 2003. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://www.howardzinn.org/war-is-the-health-of-the-state/

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Radosh, Ronald. “Aside from That, He Was Also a Red.” The Weekly Standard. August 16, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/aside-from-that-he-was-also-a-red

- Radosh, Ronald. “Aside from That, He Was Also a Red.” The Weekly Standard. August 16, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/aside-from-that-he-was-also-a-red

- Radosh, Ronald. “Aside from That, He Was Also a Red.” The Weekly Standard. August 16, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/aside-from-that-he-was-also-a-red

- Flynn, Daniel J. “An FBI History of Howard Zinn.” City Journal. August 19, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.city-journal.org/html/fbi-history-howard-zinn-10752.html

- Flynn, Daniel J. “An FBI History of Howard Zinn.” City Journal. August 19, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.city-journal.org/html/fbi-history-howard-zinn-10752.html

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Beneke, Chris; and Randall Stephens. “Lies the Debunkers Told Me: How Bad History Books Win Us Over.” The Atlantic. July 24, 2012. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2012/07/lies-the-debunkers-told-me-how-bad-history-books-win-us-over/260251/

- Kazin, Michael. “Howard Zinn’s History Lessons.” Dissent. Spring 2004. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/howard-zinns-history-lessons

- “Michael Kazin.” Georgetown University. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://gufaculty360.georgetown.edu/s/contact/00336000014RfPKAA0/michael-kazin

- Klehr, Harvey. “War of Necessity.” Weekly Standard. November 19, 2012. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/war-of-necessity

- Wineburg, Sam. “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short.” American Educator. Winter 2012-2013. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Wineburg.pdf

- Wineburg, Sam. “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short.” American Educator. Winter 2012-2013. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Wineburg.pdf

- “THE CONSCIENCE OF THE PAST.” Flagpole. February 18, 1998. Accessed from the original October 17, 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20010525003828/http://www.flagpole.com/Issues/02.18.98/lit.html

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Powell, Michael. “Howard Zinn, Historian, Dies at 87.” New York Times. January 27, 2010. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/28/us/28zinn.html

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Powell, Michael. “Howard Zinn, Historian, Dies at 87.” New York Times. January 27, 2010. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/28/us/28zinn.html

- Powell, Michael. “Howard Zinn, Historian, Dies at 87.” New York Times. January 27, 2010. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/28/us/28zinn.html

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Glavin, Paul; and Chuck Morse. “War is the Health of the State.” HowardZinn.org. March 22, 2003. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://www.howardzinn.org/war-is-the-health-of-the-state/

- “Top Secret: The Battle for the Pentagon Papers – Timeline.” USC Annenberg School for Journalism and Communications. Accessed October 22, 2019. http://topsecretplay.org/timeline/

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Glavin, Paul; and Chuck Morse. “War is the Health of the State.” HowardZinn.org. March 22, 2003. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://www.howardzinn.org/war-is-the-health-of-the-state/

- Radosh, Ronald. “Aside from That, He Was Also a Red.” The Weekly Standard. August 16, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/aside-from-that-he-was-also-a-red

- Radosh, Ronald. “Aside from That, He Was Also a Red.” The Weekly Standard. August 16, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/aside-from-that-he-was-also-a-red

- Radosh, Ronald. “Aside from That, He Was Also a Red.” The Weekly Standard. August 16, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/aside-from-that-he-was-also-a-red

- Radosh, Ronald. “Aside from That, He Was Also a Red.” The Weekly Standard. August 16, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/aside-from-that-he-was-also-a-red

- Radosh, Ronald. “Aside from That, He Was Also a Red.” The Weekly Standard. August 16, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/aside-from-that-he-was-also-a-red

- Radosh, Ronald. “Aside from That, He Was Also a Red.” The Weekly Standard. August 16, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/aside-from-that-he-was-also-a-red

- Radosh, Ronald. “Aside from That, He Was Also a Red.” The Weekly Standard. August 16, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/aside-from-that-he-was-also-a-red

- Flynn, Daniel J. “An FBI History of Howard Zinn.” City Journal. August 19, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.city-journal.org/html/fbi-history-howard-zinn-10752.html

- Flynn, Daniel J. “An FBI History of Howard Zinn.” City Journal. August 19, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.city-journal.org/html/fbi-history-howard-zinn-10752.html

- Flynn, Daniel J. “An FBI History of Howard Zinn.” City Journal. August 19, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.city-journal.org/html/fbi-history-howard-zinn-10752.html

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Radosh, Ronald. “Aside from That, He Was Also a Red.” The Weekly Standard. August 16, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/aside-from-that-he-was-also-a-red

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Riley, Naomi Schaefer. “Reclaiming History from Howard Zinn.” Wall Street Journal. May 17, 2019. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.wsj.com/articles/reclaiming-history-from-howard-zinn-11558126202

- Handlin, Oscar. “Arawaks.” The American Scholar. Autumn 1980. Accessed from the original October 18, 2019. https://d3aencwbm6zmht.cloudfront.net/asset/97521/A_Handlin_1980.pdf

- Beneke, Chris; and Randall Stephens. “Lies the Debunkers Told Me: How Bad History Books Win Us Over.” The Atlantic. July 24, 2012. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2012/07/lies-the-debunkers-told-me-how-bad-history-books-win-us-over/260251/

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Duberman, Martin. Howard Zinn: A Life on the Left. The New Press. New York: London. 2012. Quote accessed online October 17, 2019. https://books.google.com/books?id=VCqmA95DdNkC&pg=PT197&lpg=PT197&dq=%22is+treated+as+mainly+the+story+of+relentless+exploitation+and+deceit%22&source=bl&ots=dYl5cLew6y&sig=ACfU3U1nodjvc35QS7n4Iy19VVelyXQmAw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiG_d6ItqPlAhUPRqwKHVd7BlAQ6AEwAHoECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=%22is%20treated%20as%20mainly%20the%20story%20of%20relentless%20exploitation%20and%20deceit%22&f=false

- Duberman, Martin. Howard Zinn: A Life on the Left. The New Press. New York: London. 2012. Quote accessed online October 17, 2019. https://books.google.com/books?id=VCqmA95DdNkC&pg=PT197&lpg=PT197&dq=%22is+treated+as+mainly+the+story+of+relentless+exploitation+and+deceit%22&source=bl&ots=dYl5cLew6y&sig=ACfU3U1nodjvc35QS7n4Iy19VVelyXQmAw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiG_d6ItqPlAhUPRqwKHVd7BlAQ6AEwAHoECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=%22is%20treated%20as%20mainly%20the%20story%20of%20relentless%20exploitation%20and%20deceit%22&f=false

- “THE CONSCIENCE OF THE PAST.” Flagpole. February 18, 1998. Accessed from the original October 17, 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20010525003828/http://www.flagpole.com/Issues/02.18.98/lit.html

- “FAQ.” Zinn Education Project. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.zinnedproject.org/about/faq/

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- Greenberg, David. “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history.” The New Republic. March 19, 2013. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/112574/howard-zinns-influential-mutilations-american-history

- “Michael Kazin.” Georgetown University. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://gufaculty360.georgetown.edu/s/contact/00336000014RfPKAA0/michael-kazin

- Kazin, Michael. “Howard Zinn’s History Lessons.” Dissent. Spring 2004. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/howard-zinns-history-lessons

- Kazin, Michael. “Howard Zinn’s History Lessons.” Dissent. Spring 2004. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/howard-zinns-history-lessons

- Wilentz, Sean. “Making the Case for … Hillary Clinton.” Newsweek. November 16, 2007. Accessed from the original October 17, 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20080418091742/http://blog.newsweek.com/blogs/stumper/archive/2007/11/16/making-the-case-for-hillary-clinton-by-sean-wilentz.aspx

- Wilentz, Sean. “George W. Bush: The Worst President in History?” Rolling Stone. May 4, 2006. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/george-w-bush-the-worst-president-in-history-192899/

- “An Expert’s History of Howard Zinn.” Los Angeles Times. February 1, 2010. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2010-feb-01-la-oe-miller1-2010feb01-story.html

- “An Expert’s History of Howard Zinn.” Los Angeles Times. February 1, 2010. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2010-feb-01-la-oe-miller1-2010feb01-story.html

- Haynes, John Earl; and Harvey Klehr. “The Historiography of Soviet Espionage and American Communism: from Separate to Converging Paths.” “International Communism and Espionage” session, European Social Science History Conference. March 2006. Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Accessed August 15, 2019. http://www.johnearlhaynes.org/page101.html

- Klehr, Harvey. “War of Necessity.” Weekly Standard. November 19, 2012. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/war-of-necessity

- Handlin, Oscar. “Arawaks.” The American Scholar. Autumn 1980. Accessed from the original October 18, 2019. https://d3aencwbm6zmht.cloudfront.net/asset/97521/A_Handlin_1980.pdf

- Handlin, Oscar. “Arawaks.” The American Scholar. Autumn 1980. Accessed from the original October 18, 2019. https://d3aencwbm6zmht.cloudfront.net/asset/97521/A_Handlin_1980.pdf

- Riley, Naomi Schaefer. “Reclaiming History from Howard Zinn.” Wall Street Journal. May 17, 2019. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.wsj.com/articles/reclaiming-history-from-howard-zinn-11558126202

- Riley, Naomi Schaefer. “Reclaiming History from Howard Zinn.” Wall Street Journal. May 17, 2019. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.wsj.com/articles/reclaiming-history-from-howard-zinn-11558126202

- Radosh, Ronald. “Why Conservatives Are So Upset with Thomas Woods’s Politically Incorrect History Book.” History News Network. March 6, 2005. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/10493

- Radosh, Ronald. “Commies: A Journey Through the Old Left, the New Left, and the Leftover Left.” Encounter Books: San Francisco. 2001.

- Radosh, Ronald. “Why Conservatives Are So Upset with Thomas Woods’s Politically Incorrect History Book.” History News Network. March 6, 2005. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/10493.

- Wineburg, Sam. “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short.” American Educator. Winter 2012-2013. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Wineburg.pdf

- Wineburg, Sam. “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short.” American Educator. Winter 2012-2013. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Wineburg.pdf

- Wineburg, Sam. “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short.” American Educator. Winter 2012-2013. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Wineburg.pdf

- Wineburg, Sam. “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short.” American Educator. Winter 2012-2013. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Wineburg.pdf

- Wineburg, Sam. “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short.” American Educator. Winter 2012-2013. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Wineburg.pdf

- Wineburg, Sam. “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short.” American Educator. Winter 2012-2013. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Wineburg.pdf

- Wineburg, Sam. “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short.” American Educator. Winter 2012-2013. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Wineburg.pdf

- Wineburg, Sam. “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short.” American Educator. Winter 2012-2013. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Wineburg.pdf

- Zinn, Howard. “A People’s History of the United States.” Harper Collins Publishers: New York. 2003. Accessed online: libcom.org/library/peoples-history-of-united-states-howard-zinn

- Zinn, Howard. “A People’s History of the United States.” Harper Collins Publishers: New York. 2003. Accessed online: libcom.org/library/peoples-history-of-united-states-howard-zinn

- Haynes, John Earl; and Harvey Klehr. “The Historiography of Soviet Espionage and American Communism: from Separate to Converging Paths.” “International Communism and Espionage” session, European Social Science History Conference. March 2006. Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Accessed October 21, 2019. http://www.johnearlhaynes.org/page101.html

- Stern, Sheldon M. “Howard Zinn Briefly Recalled.” History News Network. February 9, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/122924

- Stern, Sheldon M. “Howard Zinn Briefly Recalled.” History News Network. February 9, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2019. https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/122924

- Wineburg, Sam. “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short.” American Educator. Winter 2012-2013. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Wineburg.pdf

- Wineburg, Sam. “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short.” American Educator. Winter 2012-2013. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Wineburg.pdf