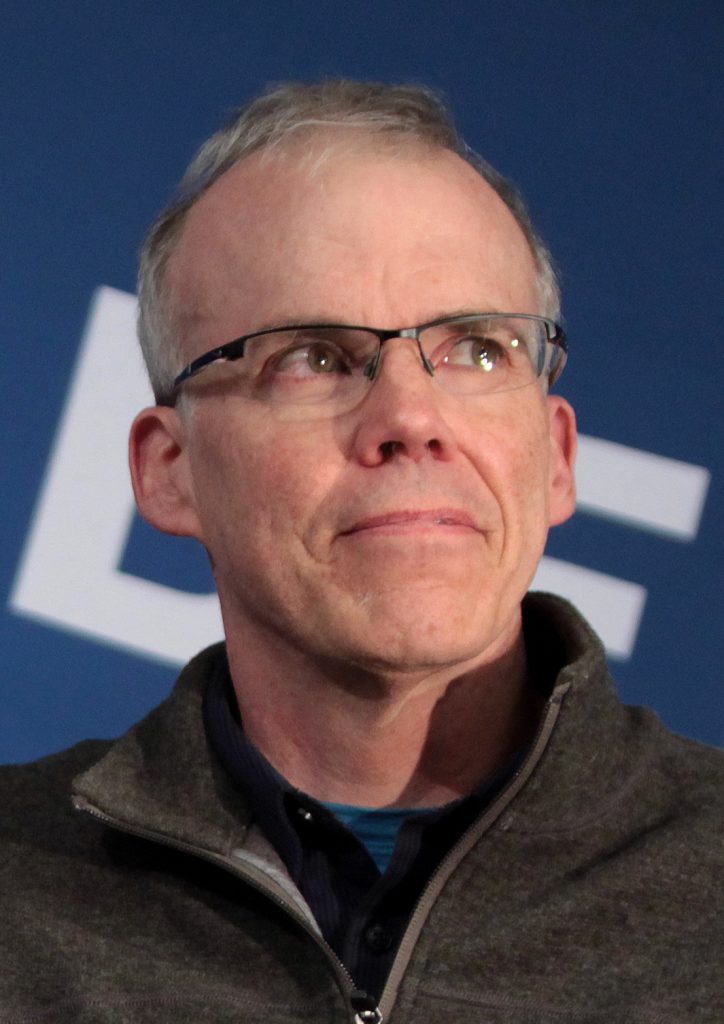

Bill McKibben is an influential environmentalist author and activist. A former journalist who wrote a seminal book in the anthropogenic global warming movement, McKibben founded the environmentalist organization 350.org and has been involved in the People’s Climate Marches movement.

McKibben’s first book, The End of Nature, has been described as “the first popular book about climate change”1 and he has been described by other climate authors as the “the godfather of all popular works of climate literature.”2 McKibben’s subsequent books all generally espoused a similar theme3 arguing that human consumerism in the developed world has pushed the earth to its physical limits and that humans need to adopt a drastic new minimalist ethos to stave off environmental peril

In 2007, McKibben transitioned from ideological writing to political activism.4 He created the influential environmentalist group 350.org in an effort to enact global mandates5 that would reduce atmospheric CO2 levels to 350 parts per million. 6 McKibben has been an active opponent of the Keystone XL oil pipeline7 and proponent of ceasing investment in traditional energy companies. 8

In 2014 McKibben was a key leader in the People’s Climate March, which was attended by prominent liberal environmental activists such as Former Vice President Al Gore, U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders (I-Vermont), and actor Leonardo DiCaprio, and which sought to support international United Nations-based environmental policies.9 In 2017, McKibben led a second People’s Climate March in Washington, D.C. in support of a 100% renewable energy mandate bill sponsored by Sen. Sanders in coordination with McKibben.10

Personal History

William “Bill” E. McKibben was born in Palo Alto, California, in 1960 and attended high school in Lexington, Massachusetts. McKibben’s father Gordon was a journalist for Business Week and then the Boston Globe. 11 In 1971, Gordon McKibben was arrested for protesting the Vietnam War.12

McKibben attended Harvard University beginning in 1978. During college McKibben served as editor of the Harvard Crimson newspaper. In the McKibben Reader 2008, McKibben wrote that while at Harvard his “leftism grew more righteous,” even though as a white, straight male he could “not realistically claim to be a victim of anything.”13

After graduating from Harvard in 1982, McKibben worked for 5 years at the New Yorker.14 While writing an article for the New Yorker about homelessness, McKibben lived on the streets of New York and during that time he met his future wife, Sue Halpern, “a former Rhodes scholar and writer who was working as a homeless advocate.”15

In 1987, McKibben left the New Yorker to work as a freelance writer and moved with Halpern to upstate New York.16 According to McKibben’s writings while he was living “on the edge of the wilderness” in upstate New York, he “finally found” the liberal cause he could take up as his own, environmentalism.17

Environmental Author

“The End of Nature”

In 1989 McKibben, at the age of 29, published The End of Nature, which has called “the first popular book about climate change.”18 To publish this book, McKibben consulted with a number of left-of-center organizations including the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and the Environmental Defense Fund. 19

Further Matthew Nisbet a fellow at American University’s Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy wrote that McKibben argues that technology will not be able to fully remediate climate change and thus concludes that the “only moral path to survival” is to transform what McKibben called “the defiant, consumptive course we’ve traditionally followed” by compelling a more minimalist lifestyle and a reduction in world population.20

The End of Nature received mixed reviews. Boston Globe columnist Ellen Goodman called it a “stunning book on global warming,” and “Globe, staff writer Ray Murphy called the book a ‘righteous jeremiad for our beleaguered planet.’”21

However, other reviewers took issue with McKibben’s views of nature over humans, and his broad environmental pronouncements.

Newsweek’s Geoffrey Cowley wrote, “most of the book is devoted to fatuous pronouncements about the nature of nature and empty prescriptions for reviving it” and concluded that the book wasn’t “about solving real-world problems.”22

New York Times science journalist Nicholas Wade wrote that McKibben was “too glib in assuming” that climate change was “an already certain outcome” given that climatologists of the time were wary to make the same claim. 23

Historian Daniel Kevles writing for the New York Review of Books criticized McKibben’s “core argument that ecosystems should take priority over human suffering” as “inhumane.” 24

McKibben’s The End of Nature ultimately served as an influence for other authors who published similarly themed books. Former Boston Globe investigative reporter Ross Gelbspan said that McKibben’s work had inspired him to write his own book on climate change and called him “the godfather of all popular works of climate literature.”25

Subsequent Writings

Bill McKibben has written at least thirteen books, one catalogue of personal writings, and edited a compilation of various global warming articles.26

McKibben also writes numerous magazine articles, major newspaper op-eds, and blog posts annually to compliment the themes in his books. His writings have appeared in the New York Review of Books, The Nation, Rolling Stone, the New York Times, the Washington Post and online outlets such as Huffington Post and the Nation Institute’s TomDispatch.com. He has also written on environmental issues for Outside, National Geographic, Audubon, and Sierra magazines.27

In his 2007 book Deep Economy: The Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future McKibben proposed that “continuing to expand the economy may be impossible.”28 McKibben had written previously on similar anti-consumer themes in many of his previous works; in 1992’s The Age of Missing Information, McKibben “argued that television is a main driver of mindless consumption and the loss of community.”29

McKibben wrote the 1998 book Maybe One: A Case for Smaller Families, which made the case for a one-child policy as a remedy to the problem of over-population. 30

Environmental Activism

In the late 2000s McKibben began organizing environmentalist activities across the nation to create a political power base for environmentalists.31 McKibben “transformed his public profile” and became “the most prominent climate change activist in the United States.”32

In 2006 McKibben, then a scholar-in-residence at the fanatically left-wing Middlebury College devised a plan to lead Middlebury students in a 2006 march that he hoped would lead to the marchers’ arrests in order to “get people riled up” for climate-based reforms. After the police informed McKibben’s group that they would not make arrests, the march was transformed into a five-day hike. 33

350.org

Also see 350.org (Nonprofit)

McKibben and six students from Middlebury College “founded 350.org after the Step It Up actions of 2007 in order to build ‘a global grassroots movement to solve the climate crisis.’”34 The organization drew its name from scientist James Hansen’s claim that “350 parts per million was the ‘safe’” atmospheric carbon dioxide level, and a goal “to avoid the worst effects of climate change.”35

350.org’s “main goal was to use Internet-enabled organizing strategies to increase the intensity of political activity among the so-called ‘issue public’ on climate change,” which appealed “directly to the base of readers and fans he [McKibben] had built up over the past 20 years.” 36

In 2010, McKibben and his 350.org group organized a global day of action that sought to secure “an international binding agreement on emissions at the December 2010 climate summit in Copenhagen, Denmark.” McKibben took credit for organizing 5,500 actions in 181 countries; no binding agreement was reached.37

Keystone XL Pipeline Opposition

In November 2011 McKibben “played a central role” in pushing the Obama administration to delay approval of the Keystone XL pipeline, which would link Canadian oil fields with refineries and distribution centers along the Gulf of Mexico. 38

McKibben has led numerous protests in opposition to the pipeline. In August 2011 he was arrested at the White House for protesting the pipeline and spent two days in jail.39 Then in November 2011 he led a 5,000-person protest at the White House hoping to convince President Barack Obama to block the pipeline project.40 McKibben was again arrested protesting against the pipeline at the White House in 2013.41 McKibben was also arrested for similar protests in 2015 against Exxon in Vermont42 and in 2016 against a proposed gas storage project at Seneca Lake, NY.43

Joining McKibben and 350.org in pressuring the White House against the Keystone XL Pipeline were the Sierra Club and the Obama administration’s former “green jobs czar” Van Jones.44

Financial Divestment Advocacy

In 2012, McKibben began “pressuring universities and other institutions to divest their financial holdings from fossil fuel companies.” 45

McKibben argued that oil, coal and natural gas companies needed to be viewed in a new light as “a rogue industry, reckless like no other force on Earth” and as “Public Enemy Number One to the survival of our planetary civilization.”46

McKibben’s article on this issue has been widely distributed on social media platforms, and in November 2012, McKibben launched a 21-city tour to encourage divestment from fossil fuel companies. 47

In 2016, McKibben called upon environmentalists to fiercely resist the administration of newly elected President Donald Trump. McKibben suggested that environmentalists make life difficult for fossil fuel executives through “fossil fuel divestment and through fighting every pipeline and every coal port.”48

Climate Marches

In 2014 the first “People’s Climate March” was attended by approximately 310,000 people and was attended by other a number of high profile environmentalists including Leonardo DiCaprio, Jane Goodall and Vandana Shiva; policymakers such as Senators Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.), Bernie Sanders (I-Vermont), Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.); then-U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon; and former Vice President Al Gore.49 The march, which took place in New York City, was coordinated to coincide with a United Nations meeting that would discuss environmentalist initiatives.50

In 2017, McKibben’s 350.org was a “key organization”51 for another People’s Climate March that took place in Washington, D.C.52 According to NPR, McKibben hoped to use the D.C. march to oppose environment-related policy decisions by the Trump administration.53

McKibben also hoped to use the 2017 march to expand environmentalists’ agenda to include a 100% renewable energy mandate. As NPR reported “A couple of days before the march, he [McKibben] joined U.S. Sens. Bernie Sanders and Jeff Merkley [D-Oregon] as they introduced legislation with a goal of putting the U.S. on 100 percent renewable power by 2050.”54

“Functionally Extinct” Koala Bears

In November 2019, McKibben tweeted out a Forbes article55 detailing the damages done to the Koala population after a rash of bushfires Australia. He wrote, in response, “And yet big banks lend big money to big oil—more every year.” 56

Democratic Party Activism

2016 Presidential Election

During the 2016 presidential election, McKibben served as a proxy for Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, and was one of Sanders’ appointees to the Democratic Party’s platform drafting commission. While serving on this commission, he proposed seven climate related amendments, including “a fracking ban, a carbon tax, a prohibition against drilling or mining fossil fuels on public lands, a climate litmus test for new developments, an end to World Bank financing of fossil fuel plants.” 57 All but one of his proposals were too radical for a majority of the other Democratic Party delegates and were thus defeated.58 The Clinton campaign subsequently accepted some of McKibben’s less extreme proposals.59

References

- O’Brien, Kevin. “The Violence of Climate Change: Lessons of Resistance from Nonviolent Activists.” Georgetown University Press. Washington D.C. 2017. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://books.google.com/books?id=OvcmDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA22&lpg=PA22&dq=%22the+first+popular+book+about+climate+change.%E2%80%9D+and+%22end+of+nature%22&source=bl&ots=2JK0k0ehig&sig=DuJ9FJSxyFbX4ocPTiUO1rLCjFw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjwlO7SxO7ZAhWHzVMKHcqrB0UQ6AEILDAB#v=onepage&q=%22the%20first%20popular%20book%20about%20climate%20change.%E2%80%9D%20and%20%22end%20of%20nature%22&f=false

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 32. March 2013. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 33. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 36. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 43. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 42. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 44. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 46. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Reuters Staff. “UPDATE 4-New York climate march draws hundreds of thousands.” Reuters. September 21, 2014. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/usa-climatechange-march/update-4-new-york-climate-march-draws-hundreds-of-thousands-idUSL1N0RM0QQ20140921

- Ludden, Jennifer. “Marchers Unite To Take On Trump’s Climate Policies.” NPR. April 29, 2017. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/04/29/526179637/thousands-of-marchers-expected-to-take-on-trumps-climate-policies

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Footnote 145. Accessed February 15, 2018 https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Marcel, Joyce. “Bill McKibben: The implacable enemy is physics.” Vemont Biz. April 13, 2017. Accessed March 15, 2018. http://www.vermontbiz.com/news/april/bill-mckibben-implacable-enemy-physics

- Quoted in Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Footnote 144. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 26. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 26. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 26. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- McKibben, Bill. “The Bill Mckibben Reader: Pieces from an Active Life: Job and Matthew.” Page 188. St. Martin’s Griffin. 2008. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://books.google.com/books?id=lY1R0hAHFuwC&pg=PA190&lpg=PA190&dq=%22bill+mckibben%22+and+%22on+the+edge+of+the+wilderness%E2%80%9D&source=bl&ots=Tm3w78ateV&sig=v8nTv40JVDqV0D4z_iA3_iamNhM&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwib6_6K0e7ZAhUQn1MKHZ0AAswQ6AEIKTAA#v=onepage&q=%22finally%20found%22&f=false

- O’Brien, Kevin. “The Violence of Climate Change: Lessons of Resistance from Nonviolent Activists.” Georgetown University Press. Washington D.C. 2017. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://books.google.com/books?id=OvcmDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA22&lpg=PA22&dq=%22the+first+popular+book+about+climate+change.%E2%80%9D+and+%22end+of+nature%22&source=bl&ots=2JK0k0ehig&sig=DuJ9FJSxyFbX4ocPTiUO1rLCjFw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjwlO7SxO7ZAhWHzVMKHcqrB0UQ6AEILDAB#v=onepage&q=%22the%20first%20popular%20book%20about%20climate%20change.%E2%80%9D%20and%20%22end%20of%20nature%22&f=false

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 28. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 29. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Quoted in Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 30. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Quoted in Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 31. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Quoted in Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 31. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Quoted in Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 31. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Quoted in Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 32. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Bill McKibben Website. Undated. Accessed March 15, 2018. http://www.billmckibben.com/books.html

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 33. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Mckibben, Bill. “Deep Economy: The Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future.” Page 1. Times Books. 2007. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://books.google.com/books?id=AMiU_clYEY4C&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22deep+economy%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiWoteK1O7ZAhWEuFMKHbHHArsQ6AEIKTAA#v=onepage&q=%22bumping%20up%22&f=false

- Quoted in Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 33. Footnote 203. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- McKibben, Bill. “Maybe One: A Personal and Environmental Argument for Single Child Families.” Simon & Schuster. New York. 1998. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://books.google.com/books?id=MELoi2ZReFwC&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22Maybe+One:+A+Case+for+Smaller+Families%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjluqPP1u7ZAhXGvVMKHRNjAjkQ6AEIKTAA#v=onepage&q=%22Maybe%20One%3A%20A%20Case%20for%20Smaller%20Families%22&f=false

- Rustin, Susanna. “A life in writing: Bill McKibben.” The Guardian. December 3, 2010. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/dec/06/bill-mckibben-interview

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 36. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- McKibben, Bill. “Fight Global Warming Now: The Handbook for Taking Action in Your Community.” Page 26. St. Martin’s Griffin. 2007. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://books.google.com/books?id=7qpRUWmn-rUC&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22Fight+Global+Warming+Now:+The+Handbook+for+Taking+Action+in+Your+Community%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjSmY3l2u7ZAhXFulMKHT7_AlIQ6AEIMzAC#v=onepage&q=%22riled%20up%22&f=false

- Hestres, Luis. “Preaching to the choir: Internet-mediated advocacy, issue public mobilization, and climate change.” New Media & Society. Volume 16(2). Page 329. Accessed 2014. March 15, 2018. http://www.luishestres.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Hestres-New-Media-Society-2014.pdf

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 42. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 43. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 43. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 44. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- O’Connor, Kevin. “Bill McKibben Jailed After White House Tar Sands Pipeline Protest.” Rutland Herald reprinted by Common Dreams. August 21, 2011. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.commondreams.org/news/2011/08/21/bill-mckibben-jailed-after-white-house-tar-sands-pipeline-protest

- Goldenberg, Suzanne. “Thousands protest at the White House against Keystone XL pipeline.” The Guardian. November 6, 2011. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/nov/07/keystone-xl-pipeline-protest-white-house

- Eilperin, Juliet and Mufson, Steven. “Activists arrested at White House protesting Keystone pipeline.” Washington Post. February 13, 2013. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/activists-arrested-at-white-house-protesting-keystone-pipeline/2013/02/13/8f0f1066-75fa-11e2-aa12-e6cf1d31106b_story.html

- Sheppard, Kate. “Bill McKibben Got Arrested While Protesting Outside An ExxonMobil Station.” Huffington Post. October 15, 2015. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/bill-mckibben-exxonmobile_us_561fee19e4b050c6c4a4c67d

- Steingraber, Sandra. “Bill McKibben Arrested + 56 Others in Ongoing Campaign Against Proposed Gas Storage at Seneca Lake.” EcoWatch. March 7, 2016. Accessed March 15, 2018. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.ecowatch.com/bill-mckibben-arrested-56-others-in-ongoing-campaign-against-proposed–1882187863.html

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Pages 44 and 45. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 46. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 47. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/global-warmings-terrifying-new-math-20120719

- Nisbet, Matthew. “Nature’s Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist.” Harvard University Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public, Discussion Paper Series. Page 47. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/D-78-Nisbet1.pdf

- McKibben, Bill. “Bill McKibben: Trump presidency “demands fierce resistance.” Grist. December 2, 2016. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://grist.org/election-2016/bill-mckibben-trump-presidency-demands-fierce-resistance/

- Visser, Nick. “Hundreds Of Thousands Turn Out For People’s Climate March In New York City.” Huffington Post. September 21, 2014. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/09/21/peoples-climate-march_n_5857902.html

- Reuters Staff. “UPDATE 4-New York climate march draws hundreds of thousands.” Reuters. September 21, 2014. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/usa-climatechange-march/update-4-new-york-climate-march-draws-hundreds-of-thousands-idUSL1N0RM0QQ20140921

- Ludden, Jennifer. “Marchers Unite To Take On Trump’s Climate Policies.” NPR. April 29, 2017. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/04/29/526179637/thousands-of-marchers-expected-to-take-on-trumps-climate-policies

- Levenson, Eric. “Climate protest takes on Trump’s policies — and the heat — in DC march.” CNN. April 29, 2017. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.cnn.com/2017/04/29/us/climate-change-march/index.html

- Ludden, Jennifer. “Marchers Unite To Take On Trump’s Climate Policies.” NPR. April 29, 2017. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/04/29/526179637/thousands-of-marchers-expected-to-take-on-trumps-climate-policies

- Ludden, Jennifer. “Marchers Unite To Take On Trump’s Climate Policies.” NPR. April 29, 2017. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/04/29/526179637/thousands-of-marchers-expected-to-take-on-trumps-climate-policies

- Nace, Trevor. “Fires May Have Killed Up To 1,000 Koalas, Fueling Concerns Over The Future Of The Species.” Forbes.com. November 23, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/trevornace/2019/11/23/koalas-functionally-extinct-after-australia-bushfires-destroy-80-of-their-habitat/#5f27f64a7bad

- McKibben, Bill. Twitter Post. November 23, 2019, 5:59 PM. https://twitter.com/billmckibben/status/1198375629638586373

- McKibben, Bill. “World At War.” The New Republic. August 15, 2016. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://newrepublic.com/article/135684/declare-war-climate-change-mobilize-wwii

- McKibben, Bill. “World At War.” The New Republic. August 15, 2016. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://newrepublic.com/article/135684/declare-war-climate-change-mobilize-wwii

- McKibben, Bill. “World At War.” The New Republic. August 15, 2016. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://newrepublic.com/article/135684/declare-war-climate-change-mobilize-wwii