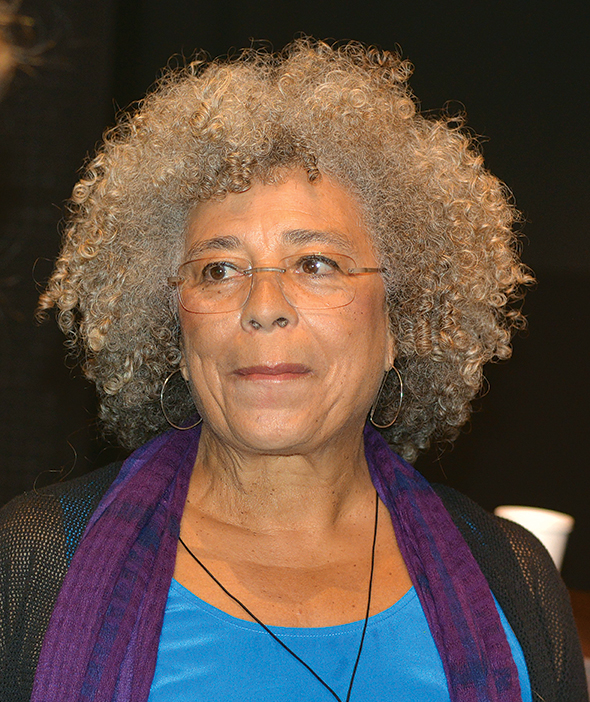

Angela Davis is a life-long, radical-left activist and academic. Davis was a longtime member of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and twice served as its vice-presidential candidate. She retired from academia in 2008 and has since been a full-time author and activist ever since.

Davis first became involved in far-left activism in high school and eagerly explored numerous radical-left organizations in college, including the Communist Party and the Black Panthers, while studying under famed critical theorist Herbert Marcuse. She was fired from her first academic job for her communist affiliation, and soon after became embroiled in a jailbreak plot connected to the Black Panthers that resulted in her imprisonment for over a year. Davis became a world-famous figure due to popular sympathy and was used by the Soviet Union as a propaganda figure both domestically and internationally. After her release, Davis became a career activist who frequently traveled to communist countries to support their regimes, while continuing her academic career in the United States. 1

In the 2020 presidential election, Davis endorsed President Joe Biden for being more easily “pressured” by the extreme left than former President Donald Trump. 2

Views

Angela Davis has been associated with Marxism, communism, radical feminism, and the Black liberation movement. She was a member of the pro-Soviet Union Communist Party USA for over twenty years and never spoke out against Soviet human rights abuses. 3 She has identified herself as a “lifelong communist,” and has critiqued capitalism as being inherently racist, sexist, and homophobic. 45

Davis has also claimed that she believed the American Communist Party was not radical enough, and that she supports moving society further to the left of popular “democratic” socialist” ideas. In an April 2009 interview with Julian Bond, Davis said, “When I joined the Communist Party, it was a difficult decision. I always considered the Communist Party to be so conservative – it was my parents’ friends. I wanted to do something more interesting and radical.” Later in the interview, Davis also said, “I spent many years as an activist in the communist party. I still imagine the possibility of moving beyond the democratic, socialist arrangement.” 6

Davis advocates for abolishing all police and prison systems, claiming that prisons are tools of capitalists to contain and oppress individuals who are not profitable for the economy. 78

Davis has spoken out against replacing former President Andrew Jackson with abolitionist Harriet Tubman on the $20 bill, claiming that doing so would obscure the alleged role capitalism played in American slavery. 9

Davis opposes the existence of the state of Israel and has supported the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement against the nation. She has called “Palestine under Israeli occupation,” an “open-air prison.” In 2019, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute rescinded a human rights award it had given to Davis due to her radical stance on Israel. 10

In January 2017, Davis was named an honorary co-chair of the Women’s March on Washington. 11

Early Life and Education

Angela Davis was born in 1944 in Birmingham, Alabama. Her father owned a service station, and her mother was a teacher who was active in the NAACP. Their neighborhood became known as “Dynamite Hill” for repeated bombings of homes owned by African Americans by the Klu Klux Klan. Davis attended all-black segregated schools and started an interracial study group in high school which the police eventually disbanded. Davis eventually transferred to Little Red School House and Elisabeth Irwin High School in New York City while her mother earned a master’s degree at New York University. In New York, Davis began learning about far-left political ideologies and joined a Marxist-Leninist organization. 1213

Davis attended Brandeis University as one of only a handful of African American students. She studied abroad in France at the Sorbonne where she was further exposed to radical-left ideas, particularly surrounding so-called post-colonialism. During Davis’s final year at Brandeis, she studied under philosopher Herbert Marcuse, one of the primary theorists of the left-of-center Frankfurt School. Davis graduated magna cum laude with a degree in French literature in 1965. 1415

Davis then attended the University of Frankfurt for two years for graduate work in philosophy. She lived with members of the left-wing Socialist German Student Union and attended some of the organization’s events. After witnessing a May Day celebration in East Berlin, Davis became sympathetic to the communist East German government, claiming that it had recovered from fascism better than West Germany. 16

In 1967, Davis returned to the United States before completing her degree to study under Marcuse at the University of California, San Diego. 17 She joined a number of radical left-wing organizations, including the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Black Panthers, Sisters Inside, and Critical Resistance. Davis then joined the Communist Party USA and the Che-Lumumba Club, an African-American faction of the Los Angeles Communist Party. 1819 In 1969, Davis was received by Cuban dictator Fidel Castro as an envoy from the American Communist Party to Cuba. 20 She received her master’s degree in philosophy in 1968. 21 In 1970, she earned a PhD in philosophy from Humboldt University of Berlin. 22

Academic Career

In 1969, Davis became an assistant professor of philosophy at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) where she taught courses on Immanuel Kant and Carl Marx. Soon after, the California Board of Regents, led by then-California Governor Ronald Reagan (R), fired Davis for her association with CPUSA. A judge ruled the firing illegal, and reinstated Davis to her position. She was fired again the following year for “inflammatory language” after accusing the Regents of murder after the death of a student at a 1969 protest at the University of California, Berkeley. 23

In 1975, after gaining notoriety as a far-left activist, Davis returned to academia as a lecturer at the Claremont Colleges. Immediately after her hiring, major donors to the schools threatened to withdraw funding. Four out of the five Claremont Colleges issued letters to its donors and alumni explaining that Davis could not be fired due to her contract. The letters promised to minimize Davis’s on campus appearances and guaranteed that she would teach in a secret location only attended by students enrolled in her class under the guard of campus security. 24

Davis later taught at the San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco State University, Rutgers University, Syracuse University, and Vassar College. 25 26 27 Davis became a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz in 1991, and retired in 2008. 28

Soledad Brothers

After her second firing from UCLA, Davis became an advocate for the “Soledad Brothers,” three inmates incarcerated for murder at Soledad Prison in Soledad, California. The men had attempted to organize a Marxist group within the prison and allegedly suffered abuse at the hands of guards as a result. After receiving numerous threats due to her activism, Davis purchased firearms that she claimed were for self-defense. 2930

In 1970, a brother of one of the Soledad Brothers used Davis’s guns to take a courtroom hostage in an attempt to free three Black Panther members on trial for murdering a guard. 31 The ensuing shootout killed four men, including the judge presiding over the trial. Davis was implicated as an accessory to the crime, and she went into hiding, which temporarily placed her on the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)’s “Ten Most Wanted List.” Davis was found and arrested in New York City. 32

In 1971, Davis declared her innocence at her first trial hearing and represented herself as a “political prisoner.” John Abt, the general counsel of the Communist Party USA, first represented Davis. 33 Davis’s supporters launched protests for her release across the world. The Rolling Stones, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, and Franz Josef Degenhardt wrote songs about Davis. 34 Schoolchildren in Moscow were required to write postcards to the United States government asking for her release. 35 A 1971 CIA report estimated that the Soviet Union directed 5% of all of its propaganda efforts that year towards the Davis affair. 36 The East German government also financed a campaign for Davis. 37

In 1972, Davis was acquitted of all charges. 38

Left-Wing Activism

After her acquittal, Davis engaged in various speaking engagements in Communist countries. In 1972 and 1974, she returned to Cuba for a speaking tour and to attend the Second Congress of the Federation of Cuban Woman. 39 In 1972, Davis traveled to the Soviet Union on invitation from the Central Committee to accept an honorary doctorate from Moscow State University. 40 That same year, Davis traveled to East Germany, where she received an honorary degree from the University of Leipzig and visited a monument to a Berlin Wall border guard who was killed while trying to prevent a family from leaving the Communist state to enter West Germany. In a speech given at the memorial, Davis encouraged people to “mourn the deaths of the border guards who sacrificed their lives for the protection of their socialist homeland.” 41

In 1977, Davis spoke by radio to the people of Jonestown, the left-wing cult compound run by Jim Jones. 42 Later that year, Jonestown was put on alert for six days out of fear of an assault by the Guyana military over a court order due to a child custody dispute. During the event, Davis sent another message to Jonestown voicing her support for the community and blaming its international scrutiny on a “conspiracy” to oppose left-wing groups. A year later, Jones led the cult to commit mass suicide. 43 In 1978, left-leaning journalist Marshal Kilduff wrote in his book, The Suicide Cult: The Inside Story of the Peoples Temple Sect and the Massacre in Guyana, that Davis had not only supported the cult, but had received financial support from Jones himself. 44 45

In 1979, Davis returned to the Soviet Union to accept the Lenin Peace Prize. 46

Political Career

In 1980 and 1984, Angela Davis ran as the running mate of Gus Hall, the Communist Party USA’s presidential nominee. 47

In 1991, Communist leaders of the Soviet Union attempted a coup against then-Soviet President Michael Gorbachev in reaction to his liberalizing policies. CPUSA, which had supported the Soviet Union almost since its founding in 1919, split on whether to support the coup, with the Committees of Correspondence faction, co-led by Davis, supporting Gorbachev’s regime. Davis and the Committees eventually split with CPUSA to form an independent political organization known as the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism. 48

Davis supported former President Barack Obama in his 2008 and 2012 presidential campaigns. In 2012, she asserted that President Obama “identifies with the black radical tradition.” 49

In 2020, Davis supported President Joe Biden’s campaign. She stated in a video that though she did not agree with most of President Biden’s views, she believed he could “be most effectively pressured by the left” and the “evolving anti-racist movement.” 50

References

- Farber, Paul M. “A Wall of Our Own: An American History of the Berlin Wall.” Google Books. February 17, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://books.google.com/books?id=RvXGDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA97#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Telusma, Blue. “Angela Davis backs Biden because he ‘can be most effectively pressured’ by the left.” The Grio. July 14, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://thegrio.com/2020/07/14/angela-davis-backs-biden/.

- Young, Cathy. “The Real Stain on Angela Davis’ Legacy Is Her Support for Tyranny.” The Bulwark. January 23, 2019. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://thebulwark.com/the-real-stain-on-angela-davis-legacy-is-her-support-for-tyranny/.

- Smith, Haley. “Angela Davis Proclaims She’s A ‘Lifelong Communist,’ Audience Erupts In Applause.” Young America’s Foundation. May 31, 2016. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://www.yaf.org/news/angela-davis-speaks-at-csula/.

- Smith, Haley. “Angela Davis Proclaims She’s A ‘Lifelong Communist,’ Audience Erupts In Applause.” Young America’s Foundation. May 31, 2016. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://www.yaf.org/news/angela-davis-speaks-at-csula/.

- “Angela Davis Oral History Interview.” C. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.c-span.org/video/?328898-1%2Fangela-davis-oral-history-interview.

- Telusma, Blue. “Angela Davis backs Biden because he ‘can be most effectively pressured’ by the left.” The Grio. July 14, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://thegrio.com/2020/07/14/angela-davis-backs-biden/.

- Smith, Haley. “Angela Davis Proclaims She’s A ‘Lifelong Communist,’ Audience Erupts In Applause.” Young America’s Foundation. May 31, 2016. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://www.yaf.org/news/angela-davis-speaks-at-csula/.

- Smith, Haley. “Angela Davis Proclaims She’s A ‘Lifelong Communist,’ Audience Erupts In Applause.” Young America’s Foundation. May 31, 2016. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://www.yaf.org/news/angela-davis-speaks-at-csula/.

- Young, Cathy. “The Real Stain on Angela Davis’ Legacy Is Her Support for Tyranny.” The Bulwark. January 23, 2019. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://thebulwark.com/the-real-stain-on-angela-davis-legacy-is-her-support-for-tyranny/.

- Young, Cathy. “Women’s March on Washington honors Soviet tool: Column.” USA Today. January 21, 2017. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2017/01/21/womens-march-washington-honors-soviet-tool-column/96851084/.

- “Biography of Angela Davis, Political Activist and Academic.” Thought Co. November 9, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.thoughtco.com/angela-davis-biography-3528285.

- “Angela Davis.” Fem Bio. January 26, 2009. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.fembio.org/english/biography.php/woman/biography/angela-davis/.

- “Biography of Angela Davis, Political Activist and Academic.” Thought Co. November 9, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.thoughtco.com/angela-davis-biography-3528285.

- “Angela Davis.” Fem Bio. January 26, 2009. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.fembio.org/english/biography.php/woman/biography/angela-davis/.

- Davis, Angela Y. “Angela Davis: An Autobiography.” Amazon. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.amazon.com/Angela-Davis-Autobiography-Y/dp/0717806677.

- Davis, Angela Y. “Angela Davis: An Autobiography.” Amazon. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.amazon.com/Angela-Davis-Autobiography-Y/dp/0717806677.

- “Biography of Angela Davis, Political Activist and Academic.” Thought Co. November 9, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.thoughtco.com/angela-davis-biography-3528285.

- “Angela Davis.” Fem Bio. January 26, 2009. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.fembio.org/english/biography.php/woman/biography/angela-davis/.

- Seidman, Sarah. “American Historical Society.” January 3, 2015. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://aha.confex.com/aha/2015/webprogram/Paper16621.html.

- “Angela Davis.” The History Makers. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20190331175938/https://www.thehistorymakers.org/biography/angela-davis-40.

- “Women Outlaws: Politics of Gender and Resistance in the US Criminal Justice System.” SUNY Cortlandt. Accessed February 17, 2021/ https://web.cortland.edu/nagelm/papers_for_web/davis_assata06.htm/.

- “Biography of Angela Davis, Political Activist and Academic.” Thought Co. November 9, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.thoughtco.com/angela-davis-biography-3528285.

- Holles, Everett, R. “Angela Davis Job Debated on Coast.” New York Times. November 16, 1975. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/98/03/08/home/davis-job.html.

- “Scholar, activist Angela Davis to give free lecture Oct. 12.” Campus & Community. October 1, 2010. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://news.syr.edu/blog/2010/10/01/angela-davis/.

- “Watson Professorship.” Syracuse University. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20130831065553/http://thecollege.syr.edu/administration/humanities_council/watson_professor.html.

- “Biography of Angela Davis, Political Activist and Academic.” Thought Co. November 9, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.thoughtco.com/angela-davis-biography-3528285.

- “Brown, J.M. “Angela Davis, iconic activist, officially retires from UC-Santa Cruz.” Mercury News. October 27, 2008. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://www.mercurynews.com/2008/10/27/angela-davis-iconic-activist-officially-retires-from-uc-santa-cruz/.

- “Biography of Angela Davis, Political Activist and Academic.” Thought Co. November 9, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.thoughtco.com/angela-davis-biography-3528285.

- “Angela Davis.” Fem Bio. January 26, 2009. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.fembio.org/english/biography.php/woman/biography/angela-davis/.

- Young, Cathy. “The Real Stain on Angela Davis’ Legacy Is Her Support for Tyranny.” The Bulwark. January 23, 2019. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://thebulwark.com/the-real-stain-on-angela-davis-legacy-is-her-support-for-tyranny/.

- “Angela Davis.” Fem Bio. January 26, 2009. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.fembio.org/english/biography.php/woman/biography/angela-davis/.

- Abt, John J.; Myerson, Michael. “Advocate and Activist: Memoirs of an American Communist Lawyer.” Google Books. 1993. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://books.google.com/books?id=9REaIPPh4k4C.

- “Angela Davis.” Fem Bio. January 26, 2009. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.fembio.org/english/biography.php/woman/biography/angela-davis/.

- Young, Cathy. “The Real Stain on Angela Davis’ Legacy Is Her Support for Tyranny.” The Bulwark. January 23, 2019. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://thebulwark.com/the-real-stain-on-angela-davis-legacy-is-her-support-for-tyranny/.

- Hannah, Jim. “Revolutionary Research.” Wright State University. August 24, 2017. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://webapp2.wright.edu/web1/newsroom/2017/08/24/revolutionary-research/.

- Slobdian, Quinn. “Comrades of Color: East Germany in the Cold War World.” Google Books. December 1, 2015. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://books.google.com/books?id=g6UHCAAAQBAJ.

- “Angela Davis.” Fem Bio. January 26, 2009. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.fembio.org/english/biography.php/woman/biography/angela-davis/.

- Seidman, Sarah. “American Historical Society.” January 3, 2015. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://aha.confex.com/aha/2015/webprogram/Paper16621.html.

- Graaf, Beatrice de. “Evaluating Counterterrorism Performance: A Comparative Study.” Google Books. 2011. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://books.google.com/books?id=we6rAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA199#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Farber, Paul M. “A Wall of Our Own: An American History of the Berlin Wall.” Google Books. February 17, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://books.google.com/books?id=RvXGDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA97#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Reiterman, Tim. “Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People.” Amazon. November 13, 2008. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.amazon.com/Raven-Untold-Story-Jones-People/dp/1585426784

- “Statement of Angela Davis (Text).” Jonestown. May 29, 2013. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=19027.

- Kilduff, Marshall, and Ron Javers. Essay. In The Suicide Cult: The inside Story of the Peoples TEMPLE Sect and the Massacre in Guyana, 46. New York: Bantam Books, 1978.

- Walter, Scott. “Radical Lives Matter.” Capital Research Center. Capital Research Center, November 18, 2020. https://capitalresearch.org/article/radical-lives-matter/.

- “Angela Davis.” Fem Bio. January 26, 2009. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.fembio.org/english/biography.php/woman/biography/angela-davis/.

- Goodman, Walter. “Hall, at 74, Still Seeks Presidency.” New York Times. November 2, 1984. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/1984/11/02/us/hall-at-74-still-seeks-presidency.html.

- Brzuzy, Stephanie; Lind, Amy. “Battleground: Women, Gender, and Sexuality.” Google Books. 2007. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://books.google.com/books?id=CdoIS5YdygkC&pg=PA406.

- “Angela Davis Has Lost Her Mind Over Obama.” Black Agenda Report. March 28, 2012. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.blackagendareport.com/content/angela-davis-lost-her-mind-over-obama.

- Telusma, Blue. “Angela Davis backs Biden because he ‘can be most effectively pressured’ by the left.” The Grio. July 14, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://thegrio.com/2020/07/14/angela-davis-backs-biden/.