The “Fight for $15” is a corporate campaign principally orchestrated and funded by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) which seeks to unionize the quick-service franchise restaurant industry and raise the federal minimum wage by more than double to $15 per hour, using the slogan “$15 and a union.”1 The campaign is heavily organized by the SEIU, a number of SEIU-funded left-wing pressure groups known by the catchall phrase “worker centers,” and the SEIU’s public relations consultants, BerlinRosen.2

The campaign obtained substantial media coverage through the efforts of its consultants BerlinRosen and a series of walkouts ostensibly by employees of fast food restaurants which began in late November 2012, shortly after the 2012 presidential election.3 The campaign has staged repeated walkouts throughout the years since. The SEIU organized an SEIU-affiliated National Fast Food Workers Union at some point in 2017, supporting it with $1.5 million in funds from October through the end of the year; the union reported no members at year end.4

The campaign has had mixed success. As of early 2018, some left-wing jurisdictions, including California, New York State, the District of Columbia, and a number of municipalities, have enacted a $15 per hour minimum wage law which will take effect by the 2020s, though no hike has been enacted at the federal level.5 During the Obama administration, the National Labor Relations Board backed the campaign’s demand that franchise employers—national branding companies whose names are on the door of independently owned and operated restaurant and other service businesses—be considered “joint employers” subject to legal liability for the local employers’ business practices.6

The Fight for $15 was rocked in late 2017 by a number of scandals involving workplace practices and behavior by prominent campaign leaders. An SEIU executive vice president credited as a “key creator”7 of the campaign was suspended and later resigned after staffers alleged that he had engaged in inappropriate sexual relationships with subordinates who were later promoted, violating SEIU’s anti-nepotism policies.8 Other Fight for $15 campaign organizers in New York and Detroit also resigned amid allegations of improper workplace conduct9 and a leading Chicago organizer was fired after being accused of “abusive and aggressive behavior” by his subordinates.10

Background

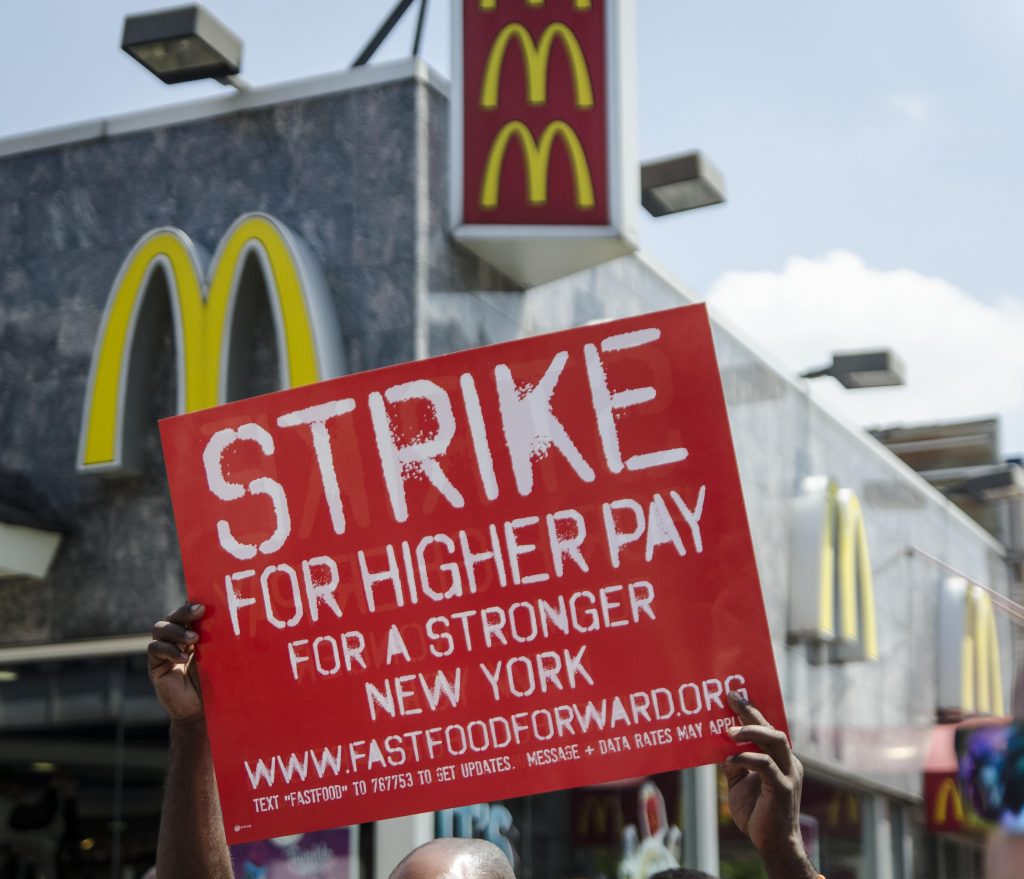

In late November 2012, union activists and a claimed 200 employees of quick-service restaurants in New York City held a series of demonstrations for a $15 minimum wage and the unionization of restaurants under the banner of “Fast Food Forward.” Groups supporting the demonstrations included New York Communities for Change (NYCC), UnitedNY, the Black Institute, and the SEIU; city Democratic politicians also backed the demonstrations.11 Reports suggested that as many as 40 organizers associated with NYCC, a pressure group descended from the defunct ACORN organizing network, were involved with recruiting workers to become involved in the campaign.12

The SEIU has intended to unionize the quick-service restaurant industry for some time. In 2009, the SEIU drafted a plan to unionize the industry after the passage of the card-check bill (which did not pass); many of the tactics outlined, including “[choosing] metro areas with a favorable local political environment and workforce composition,” “[using] a living wage as a vehicle to excite, build momentum, build worker lists/ID potential leaders,” and “[bringing] workers together across companies within geographic clusters” would be employed by Fight for $15.13

The SEIU has targeted the quick-service restaurant industry in part because of low levels of present unionization and also because the turnover of employees in the industry creates a substantial revenue stream for the union in the form of initiation fees, which are mandatory in states without a right-to-work law.14 One Manhattan Institute scholar estimated that the return to the SEIU for unionizing half of employees in McDonald’s restaurants alone would exceed $100 million per year in dues, initiation fees, and compelled “agency fees” in forced-unionism states.15

Leading Organizations

SEIU

Also see Service Employees International Union (Labor Union)

The Service Employees International Union (SEIU) has principally funded and led the organization of the Fight for $15. From the outset of the organization of the campaign, the SEIU has served as the campaign’s principal funder with a goal of unionizing fast-food workers. Reports indicated that SEIU personnel trained activists associated with local left-wing community organizing groups that received SEIU funding to support the campaign, even before the first public demonstrations in late 2012.16

The chief strategist of the campaign (until his resignation from the union over allegations of workplace misconduct in late 2017) was Scott Courtney, an executive vice president of the SEIU.17 Courtney received $308,284 in total disbursements of which $190,460 was gross salary in 2017, the most recent year he was employed by the SEIU.18 Courtney expressed the desire to build “a larger workers’ organization to push on wages, health coverage, pensions, scheduling and sick days,” with a labor agreement (whether or not it followed traditional National Labor Relations Act collective bargaining rules) with McDonald’s as the first step.19

Other SEIU officials were installed as leaders of the “worker organizing committees” which formed the ground game of the Fight for 15. A review conducted in late 2013 showed that five such committees (the Fast Food Workers Committee in New York, the Workers Organizing Committee of Chicago, the Michigan Workers Organizing Committee, the St. Louis Organizing Committee, and the Milwaukee Workers Organizing Committee) were all led by SEIU international or SEIU local union employees or officers.20

In 2017, the campaign organized a new National Fast Food Workers Union. As of year-end 2017, it reported no members to the federal government and had formally affiliated with the SEIU.21

BerlinRosen

Also see BerlinRosen (For-Profit)

BerlinRosen, a communications firm which has worked on behalf of numerous left-wing politicians and political causes, has been deeply involved in the Fight for $15 campaign since its creation. The consultancy reportedly has handled nationwide media relations and communications strategy for the campaign.22

BerlinRosen has been identified as being the source of talking points for demonstrating workers, having badgered newspapers not to publish pieces identifying drawbacks to a $15 per hour minimum wage, and serving as the media relations representatives for individual strikers.23

The National Employment Law Project, an SEIU-funded advocacy group which supports the Fight for $15 with local policy development, has also retained BerlinRosen as a media consultant.24

Other Campaign Consultants

A number of law firms, political consultancies, and field canvassing firms serving the SEIU have been linked to the Fight for $15. Ardleigh Group, a field canvassing firm which has worked for Democratic political campaigns in addition to SEIU,25 reportedly has paid the SEIU-hired staff working on the Fight for $15.26 In 2016 and 2017, the Fast Food Workers Committee, an almost-entirely-SEIU-funded organization involved in Fight for $15, paid Ardleigh Group over $1.1 million for “contract services” and “contracted services.”27 In 2015, the Los Angeles Organizing Committee paid Ardleigh Group $900,000 for “payroll services.”28

The SEIU has expanded the campaign beyond North America in order to increase pressure on McDonald’s to agree to allow SEIU to unionize its American employees. SEIU spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to hire a Brazilian law firm, Piza Advogados Associados, to pressure the largest McDonald’s franchise in the country;29 the SEIU investment in the effort dropped off substantially in 2017.30

Worker Centers

In the early period of the campaign, before a series of “Worker Organizing Committees” were registered with the federal Department of Labor as labor unions, the Fight for $15 was driven by a series of left-wing nonprofit advocacy groups known broadly as “worker centers.”31

New York Communities for Change

Also see New York Communities for Change (Nonprofit)

New York Communities for Change (NYCC), a worker center descended from the controversial ACORN network of community organizing groups, was a key entity in the demonstrations surrounding the campaign from its beginning. Drawing on support from Occupy Wall Street and other left-wing organizing campaigns and millions of dollars in SEIU financial support, NYCC assisted in canvassing in preparation for the first demonstrations in 2012.32

From 2013 through 2016, NYCC received over $3 million in support from SEIU, including contributions passed through the Fast Food Workers Committee labor union.33 Jonathan Westin, the executive director of NYCC, served as the vice president of FFWC until its dissolution in 2017.34

Jobs with Justice

Also see Jobs with Justice (Nonprofit)

Jobs with Justice (JWJ) is a national coalition of worker centers and left-wing advocacy groups formed in 1987 by Larry Cohen, who would later serve as president of the Communications Workers of America labor union.35 The group operates a number of local chapters under the Jobs with Justice and other independent brands like Alliance for a Greater New York. JWJ has been involved in supporting Fight for $15 campaigns.36

The group and its subsidiaries have received substantial funding from the SEIU and also from left-wing foundations, most prominently the Ford Foundation. From 2013 through 2016, JWJ and its affiliates received nearly $4 million from the Ford Foundation; the groups also received funding from the Nathan Cummings Foundation, the Surdna Foundation, and the Annie E. Casey Foundation, among others.37

Action Now

Also see Action Now (Nonprofit)

Action Now is a Chicago-based worker center which developed from the ACORN network of left-wing activist groups after ACORN folded. Action Now was deeply involved in the initial development of the Fight for $15 campaign; reports indicated that SEIU was providing financial support to the group to prepare to stage the initial demonstrations as early as 2011. By the end of 2012, SEIU had provided Action Now with over $3 million in funds to support union organizing, mostly the Fight for $15.38

Reports indicated that SEIU and Action Now had a longstanding relationship preceding Fight for $15. One SEIU official told labor newspaper In These Times: “Action Now here is very closely connected to the largest SEIU local in the region—SEIU Healthcare Illinois/Indiana. They have a history of cooperative, overlapping campaigns.”39

Good Jobs Nation

Also see Good Jobs Nation (Other Group)

Good Jobs Nation is a partly SEIU-funded worker center most notable for demonstrations in the Washington, D.C. area.40 The group held a demonstration in 2015 with left-wing U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders (I-Vermont) demanding a $15 per hour minimum wage for service workers at the U.S. Capitol.41

Advocacy Groups

Leading liberal advocacy groups have assisted in messaging for and developing policy associated with the Fight for $15. The National Employment Law Project (NELP) and the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), both of which are closely tied to labor unions and funded by the SEIU, have played key roles in advancing the campaign. The University of California, Berkeley has two internal think tanks, the Center for Labor Research and Education and the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment (IRLE), which provide research and communications support for the campaign.42

National Employment Law Project

Also see National Employment Law Project (Nonprofit)

The National Employment Law Project (NELP) is a labor union-funded and labor union-aligned policy development shop based in New York. The group has produced methodologically questionable research in support of minimum wage increases, including the Fight for $15.43 NELP has received roughly $450,000 in support from labor unions from 2013-2016; it has received substantially more support from left-wing foundations including the Ford and W.K. Kellogg Foundations.44

In addition to providing policy development, NELP has also assisted pro-Fight for $15 politicians and advocacy groups including labor unions with communications advice. NELP additionally retains BerlinRosen as a representative for public relations.45

Economic Policy Institute

Also see Economic Policy Institute (Nonprofit)

The Economic Policy Institute (EPI) is a labor union-associated think tank and policy research organization. It is largely funded by labor unions, and AFL-CIO president Richard Trumka serves as its board chair.46

EPI has issued reports promoting the SEIU-backed campaign47 and held events promoting SEIU 775NW president David Rolf’s book on the campaign.48

U.C. Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley, maintains two labor-union-aligned policy research and communications organizations: the Center for Labor Research and Education headed by Ken Jacobs and the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment headed by Michael Reich. Both Jacobs’s and Reich’s research strongly supports the Fight for $15, and both academics have served as spokespeople for the campaign.49

Jacobs’s shop has received funding from the Service Employees International Union, which it used to commission a study coauthored by Reich defending a $15 per hour minimum wage against charges it would lead to dis-employment.50 Reich was also involved in drafting a report commissioned by then-Seattle Mayor Ed Murray (D) which was apparently commissioned to counter negative findings about the city’s $15 minimum wage from a University of Washington study commissioned by the city council.51

Other Liberal Groups

The SEIU’s campaign receives rhetorical and organizing support from a number of other liberal groups. Aaron Mair, president of the Sierra Club, a major environmentalist organization which has explored joining the AFL-CIO labor federation, has written in support of the union-backed Fight for $15.52 Another environmentalist group, 350.org, has endorsed Fight for $15 as “the fight for a livable planet.”53 Democratic politicians, most prominently 2016 Presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, have also expressed support for the campaign.54

Techniques

The Fight for $15 campaign has followed the Service Employees International Union’s “corporate campaign” model of organizing, with union-directed public demonstrations, political pressure at the local and state levels, and corporate concessions to pressure to allow unionization by the controversial public “card check” method.55

Public Demonstrations

The most notable expression of the Fight for $15 have been periodic demonstrations (so-called “fast food strikes”) by left-wing activists, workers, and professional organizers. One analysis found that Fight for $15 had organized 1,760 branded demonstrations from 2013-2016, with a maximum reach of 340 cities for a demonstration in late 2016.56

The level of worker involvement in as opposed to SEIU and BerlinRosen stage-management of the public demonstrations has been contested. Left-wing sources report that BerlinRosen had developed a guide to staging demonstrations titled “Strike in a Box,” which included guidelines for staffing a demonstration.57 An Associated Press reporter noted that at one demonstration “it wasn’t clear how many participants were fast-food workers, rather than campaign organizers, supporters or members of the public relations firm that has been coordinating media efforts.”58

After the 2016 elections, analysts found a decline in public demonstration activities as part of Fight for $15. Only 30 demonstrations were staged in the first half of 2017.59

Political Pressure

The Fight for $15 received support from local left-wing politicians from its inception in New York City in 2012. A number of political figures campaigning for the 2013 Democratic nomination for Mayor of New York City (including eventual winner Bill de Blasio) expressed support for the initial demonstrations in 2012.60

Since the campaign began, a number of left-leaning municipalities61 and the strongly Democratic Party-aligned states of California and New York have passed $15 per hour wage mandates.62 New York City enacted a mandatory employer checkoff program, allowing unions or other left-wing nonprofit groups to automatically deduct dues from workers’ wages.63

At the federal level, the National Labor Relations Board under the Obama-appointed General Counsel Richard Griffin (a former attorney for the International Union of Operating Engineers64) sought to use rulemakings to hold franchise brands (most notably McDonald’s) jointly liable for the employment practices of their independently owned franchisees.65

SEIU officials have expressed a desire for a “national bargaining table with McDonald’s, Wendy’s, and Burger King.”66 The SEIU began the campaign hoping to use legal pressure to compel the national branding companies to agree to so-called “neutrality agreements,” which would allow local franchise restaurants to be organized by public “card check” drives.67 At the direction of then-NLRB General Counsel Griffin, the NLRB opened investigations of McDonald’s and its franchisees; the cases were closed by a settlement with the NLRB after Griffin had left the agency. Pursuant to the settlement, McDonald’s continued to assert that it is not a subject to joint employer liability.68

Strike for Black Lives

On July 20, 2020, activists associated with the Fight for $15 campaign participated in the “Strike for Black Lives.” Labor unions and other organizations participated in the mass strike in 25 different cities to protest racism and acts of police violence in the United States. 69

Employees in the fast food, ride-share, nursing home, and airport industries left work to participate in the strike. Protesters sought to press elected officials in state and federal offices to pass laws that would require employers to raise wages and allow employees to unionize so that they may negotiate better health care, child support care, and sick leave policies. Protesters stressed the need for increased safety measures to protect low-wage workers who do not have the option to work from home during the coronavirus pandemic.

Organizers of the protest claimed that one of the goals of the strike is to incite action from corporations and the government that promotes career opportunities for Black and Hispanic workers. Organizers stated that the strike was inspired by the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike in 1968 over low wages, inhuman working conditions, and a disparity in the distribution of benefits to black and white employees.

They stated that the purpose of the “Strike for Black Lives” is to remove anti-union and employment policies that prevent employees from bargaining collectively for better working conditions and wages. 70

Expenditures

Since the campaign began in 2012 through the end of 2016, the Service Employees International Union has spent at least $90 million on organizing worker center groups, fees to political consultants, and subsidies for worker organizing committees and subordinate labor unions involved in the Fight for $15.71 The SEIU reportedly reduced its rate of financial support for the campaign after the November 2016 federal general elections, with the SEIU’s outside expenditures on the campaign in 2017 falling to $10.8 million from $19 million in 2016.72

Effects

As of early 2018, the effectiveness of the Fight for $15 has been contested. The federal government has not changed the minimum wage level since the campaign began; the SEIU has failed to compel McDonald’s or its franchises to bargain with the union.73

The campaign has won a number of victories to phase in a $15 minimum wage in very left-wing municipalities and the Democratic-controlled left-wing states of New York and California.74 The campaign has been less successful in securing additional members for the SEIU; despite the economic expansion, the union’s membership has declined from the end of 2011 through the end of 2017.75

Former SEIU President Andy Stern has expressed concern for the union’s financial security amid the failure of the Fight for $15 to win unionization agreements. Stern told the Wall Street Journal: “The problem for the union is when dues collected from collective bargaining is your only revenue source, a social movement like Fight for $15 transfers money from your members to a broad-based fight […] You need a different business model.”76

After the 2016 elections, Fight for $15 leadership declared an intention to take a more directly partisan approach to electoral intervention; a Labor Day 2017 demonstration series was explicitly targeted at conservative Republican governors and legislators.77

Controversies

Workplace Misconduct by Senior Officials

In late 2017, the Fight for $15 and the SEIU were rocked by a number of allegations and resignations by senior officials involved in the campaign. Scott Courtney, an SEIU executive vice president who was credited as the “chief strategist” of Fight for $15,78 resigned in disgrace in October 2017 after allegations emerged that Courtney had engaged in sexual relationships with younger women who were later promoted.79 After Courtney’s suspension, a former Fight for $15 organizer told the Washington Free Beacon that “I’m not surprised at all given the broad environment of misogyny at [the union] […] I personally experienced sexual harassment from two people in supervisory positions.” The organizer did not have personal knowledge any actions by Courtney other than those publicly known at the time.80

Courtney was not the only senior Fight for $15 official implicated in workplace misconduct. Three city coordinators for the Fight for $15, New York’s Kendall Fells, Chicago’s Caleb Jennings, and Detroit’s Mark Raleigh, all resigned or were dismissed from the union amid allegations of abusive behavior.81 Fells was accused by a former female subordinate of making inappropriate remarks about the subordinate’s appearance and personal life, incidents the accuser brought to SEIU officials’ attention in 2011.82 Jennings was charged (but later acquitted) of battery against a Fight for $15 worker, allegations which prompted 50 SEIU staffers to call for his removal.83 The allegations leading to Raleigh’s firing were unspecified.

Policy Radicalism

The central policy plank of the Fight for $15, a $15 minimum wage, would more than double the federal statutory minimum. A number of economists on the left, including those who favor higher minimum wages in general, have expressed skepticism at the claim that a $15 per hour minimum would not lead to dis-employment: They have included Obama administration Council of Economic Advisers chairs Christina Roemer and Alan Krueger and Harvard University economist and Obama administration advisor David Cutler.84 A survey of economists commissioned by the free-market Employment Policies Institute in 2015 found that nearly 75 percent of respondents opposed a federal $15 per hour minimum wage.85

The effects of the radical policy led to controversy in Seattle, Washington. After passing a multiple-year stepwise increase in the city minimum wage to $15 per hour, the city council commissioned a University of Washington research team to study the effect of the hikes on city employment. The council cut off funding to the team sometime after preliminary findings indicated the first hikes (to $13 per hour) had negative effects,86 including an average decline in monthly pay for low-wage workers of $125 per month.87 In an apparent attempt to discredit the University of Washington team’s findings, the office of Mayor Ed Murray (D)—which had pre-publication review of the findings—requested that Michael Reich of the U.C. Berkeley Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, a noted activist in favor of the Fight for $15, conduct research to show the wage mandate had no ill effect.88

Organizer Unionization Dispute

At an SEIU-staged “Fight for $15 convention” in 2016, a number of Fight for $15 organizers disrupted SEIU’s program of proceedings by presenting a demand to the SEIU that the organizers be recognized as represented by the Union of Union Representatives, a labor union which represents 75 SEIU organizers and field staff. The SEIU, holding that the organizers were employed by the almost-entirely-SEIU-funded local Worker Organizing Committees, refused to bargain.89 The Union of Union Representatives additionally alleged that SEIU was improperly outsourcing work to contractors—most prominently the Democratic-aligned canvassing firm Ardleigh Group—which should have been covered by the union’s collective bargaining agreement.90

In late 2017, after a number of SEIU officials involved in the Fight for $15 resigned or were terminated for workplace misconduct, the SEIU National Fast Food Workers Union—the successor organization to the Worker Organizing Committees—recognized the United Media Guild (a local union of the Communications Workers of America), which had represented workers for the Mid-South Organizing Committee, as the bargaining representative for 52 “organizers, communications workers, data specialists, and other office workers” working on Fight for $15.91

References

- Gruenberg, Mark. “Fight for 15 and a Union – the Future of Organizing?” Workday Minnesota. September 2, 2016. Accessed April 03, 2018. https://www.workdayminnesota.org/articles/fight-15-and-union-–-future-organizing.

- Gupta, Arun. “Fight For 15 Confidential.” In These Times. November 11, 2013. Accessed April 03, 2018. http://inthesetimes.com/article/15826/fight_for_15_confidential.

- Semuels, Alana. “Fast-food Workers Walk out in N.Y. amid Rising U.S. Labor Unrest.” Los Angeles Times. November 29, 2012. Accessed April 03, 2018. http://articles.latimes.com/2012/nov/29/business/la-fi-mo-fast-food-strike-20121129.

- National Fast Food Workers Union, SEIU (Department of Labor file number 545-670), Annual Report of a Labor Organization (Form LM-2), 2017, Schedule 13

- “State Minimum Wages | 2018 Minimum Wage by State.” National Conference of State Legislatures. January 2, 2018. Accessed April 03, 2018. http://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/state-minimum-wage-chart.aspx#Table.

- Wiessner, Daniel. “McDonalds Joint Employment Trial Delayed amid Settlement Talks.” Reuters. January 20, 2018. Accessed April 03, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-mcdonalds/mcdonalds-joint-employment-trial-delayed-amid-settlement-talks-idUSKBN1F82PV.

- Eidelson, Josh. “Fight For 15 Architect Suspended by Service Employees Union.” Bloomberg Law. October 16, 2017. Accessed April 03, 2018. https://www.bna.com/fight-15-architect-n73014470984/.

- Lewis, Cora. “A Top Labor Executive Has Resigned After Complaints About His Relationships With Female Staffers.” BuzzFeed. October 23, 2017. Accessed April 03, 2018. https://www.buzzfeed.com/coralewis/seiu-courtney-resigns?utm_term=.irqgwApL5N#.qpx3ZBOx9r.

- Lewis, Cora. “The Organizing Director Of The Fight For 15 Has Resigned Amid Harassment Investigation.” BuzzFeed. November 2, 2017. Accessed April 03, 2018. https://www.buzzfeed.com/coralewis/seiu-new-york-director-of-the-fight-for-15-resigned?utm_term=.fj2JRDK9QO#.nopx0NlKyP.

- Lewis, Cora. “The Lead Chicago Organizer of The Fight for 15 Has Been Fired Amid A Sexual Harassment Investigation.” BuzzFeed. October 24, 2017. Accessed April 03, 2018. https://www.buzzfeed.com/coralewis/fight-for-15-shakeup?utm_term=.gogPJ6Dq5g#.rhbemqANG4.

- Greenhouse, Steven. “Fast-Food Workers in New York City Rally for Higher Wages.” The New York Times. November 29, 2012. Accessed April 03, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/30/nyregion/fast-food-workers-in-new-york-city-rally-for-higher-wages.html?pagewanted=all.

- Eidelson, Josh. “In Rare Strike, NYC Fast-food Workers Walk out.” Salon. November 30, 2012. Accessed April 03, 2018. https://www.salon.com/2012/11/29/in_rare_strike_nyc_fast_food_workers_walk_out/.

- WorkPlaceReport. “SEIU’s New Burger Queen? Internal Documents Expose Plan to Unionize Fast-Food Industry.” RedState. May 14, 2010. Accessed April 03, 2018. https://www.redstate.com/diary/laborunionreport/2010/05/14/seius-new-burger-queen-internal-documents-expose-plan-to-unionize-fast-food-industry/.

- WorkPlaceReport. “SEIU Picks NYC To Launch 3-Year Old Planned Attack To Unionize Nation’s Fast-Food Industry.” RedState. November 30, 2012. Accessed April 03, 2018. https://www.redstate.com/laborunionreport/2012/11/30/seiu-picks-nyc-to-launch-3-year-old-planned-attack-to-unionize-nations-fast-food-industry/.

- Furchtgott-Roth, Diana. “McDonald’s, Already Struggling, Now Has to Fight the Government.” Economics21. February 2, 2015. Accessed April 03, 2018. https://economics21.org/html/mcdonalds-already-struggling-now-has-fight-government-1232.html.

- Gupta, Arun. “Fight For 15 Confidential.” In These Times. November 11, 2013. Accessed April 03, 2018. http://inthesetimes.com/article/15826/fight_for_15_confidential.

- Greenhouse, Steven. “Fight for $15: The Strategist Going to War to Make McDonald’s Pay.” The Guardian. August 30, 2015. Accessed April 03, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/aug/30/fight-for-15-strategist-mcdonalds-unions.

- Service Employees International Union, Annual Report of a Labor Organization (Form LM-2), 2017, Schedule 11

- Greenhouse, Steven. “Fight for $15: The Strategist Going to War to Make McDonald’s Pay.” The Guardian. August 30, 2015. Accessed April 03, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/aug/30/fight-for-15-strategist-mcdonalds-unions.

- Center for Union Facts. “Astroturfing a Worker Center 101.” LaborPains.org. November 13, 2013. Accessed April 03, 2018. http://laborpains.org/2013/11/13/astroturfing-a-worker-center-101/.

- National Fast Food Workers Union, SEIU (Department of Labor file number 545-670), Annual Report of a Labor Organization (Form LM-2), 2017, Schedule 13

- Gupta, Arun. “Fight For 15 Confidential.” In These Times. November 11, 2013. Accessed April 03, 2018. http://inthesetimes.com/article/15826/fight_for_15_confidential.

- Saltsman, Michael. “COMMENTARY: At Protests, Look for the Union Label.” Courier-Post. April 16, 2015. Accessed April 04, 2018. https://www.courierpostonline.com/story/opinion/columnists/2015/04/13/commentary-protests-look-union-label/25712067/.

- National Employment Law Project, Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax (Form 990), 2016, Part VII Section B

- Anderson, Jeffrey. “The Brandon Todd Team Struggles to Explain Its Largest Campaign Expenditure.” Washington City Paper. April 30, 2017. Accessed April 16, 2018. https://www.washingtoncitypaper.com/news/loose-lips/article/20859858/the-brandon-todd-team-struggles-to-explain-its-largest-campaign-expenditure.

- Gupta, Arun. “EXCLUSIVE: Some of SEIU’s ‘Fight for $15’ Workers Aren’t Unionized — and Don’t Make $15 an Hour.” Raw Story. August 13, 2016. Accessed April 16, 2018. https://www.rawstory.com/2016/08/exclusive-some-of-seius-fight-for-15-workers-arent-unionized-and-dont-make-15-an-hour/.

- Author’s calculations from Fast Food Workers Committee, Annual Report of a Labor Organization (Form LM-2), 2016 and 2017, Schedule 19.

- Redmond, Sean P. “SEIU Submits 2015 Financial Report.” U.S. Chamber of Commerce. April 6, 2016. Accessed April 16, 2018. https://www.uschamber.com/article/seiu-submits-2015-financial-report.

- McMorris, Bill. “SEIU Heads Over There.” Washington Free Beacon. May 29, 2015. Accessed April 16, 2018. http://freebeacon.com/issues/seiu-heads-over-there/.

- Department of Labor records showed SEIU paid Piza $400,000 in 2016 but only $50,000 in 2017.

- Center for Union Facts. “Astroturfing a Worker Center 101.” LaborPains.org. November 13, 2013. Accessed April 05, 2018. http://laborpains.org/2013/11/13/astroturfing-a-worker-center-101/.

- Scheiber, Noam. “In Test for Unions and Politicians, a Nationwide Protest on Pay.” The New York Times. April 16, 2015. Accessed April 05, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/16/business/economy/in-test-for-unions-and-politicians-a-nationwide-protest-on-pay.html.

- Manheim, Jarol. “The Emerging Role of Worker Centers in Union Organizing: An Update and Supplement.” Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America. 2017. Accessed April 5, 2018. https://www.uschamber.com/sites/default/files/uscc_wfi_workercenterreport_2017.pdf.

- Fast Food Workers Committee, Annual Report of a Labor Organization (Form LM-2), 2017, Schedule 11

- Manheim, Jarol. “The Emerging Role of Worker Centers in Union Organizing: An Update and Supplement.” Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America. 2017. Accessed April 5, 2018. https://www.uschamber.com/sites/default/files/uscc_wfi_workercenterreport_2017.pdf.

- “WE FOUGHT FOR $15 AND WON!” Long Island Jobs with Justice. September 28, 2016. Accessed April 06, 2018. https://longislandjwj.org/2015/07/23/we-fought-for-15-and-won/.

- Manheim, Jarol. “The Emerging Role of Worker Centers in Union Organizing: An Update and Supplement.” Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America. 2017. Accessed April 06, 2018. https://www.uschamber.com/sites/default/files/uscc_wfi_workercenterreport_2017.pdf.

- Gupta, Arun. “Fight For 15 Confidential.” In These Times. November 11, 2013. Accessed April 06, 2018. http://inthesetimes.com/article/15826/fight_for_15_confidential.

- Quoted in Gupta, Arun. “Fight For 15 Confidential.” In These Times. November 11, 2013. Accessed April 06, 2018. http://inthesetimes.com/article/15826/fight_for_15_confidential.

- Berman, Richard. “BERMAN: Doing Big Labor’s Dirty Work.” The Washington Times. October 03, 2013. Accessed April 06, 2018. https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2013/oct/3/berman-doing-big-labors-dirty-work/?utm_source=RSS_Feed&utm_medium=RSS

- Bordelon, Brendan. “Will Sanders’s $15 Wage Push Win Over Hillarys Union Supporters?” National Review. November 11, 2015. Accessed April 06, 2018. https://www.nationalreview.com/2015/11/sanders-15-wage-push-win-over-hillarys-union-supporters/.

- Person, Daniel. “Emails Show Mayor’s Office and Berkeley Economist Coordinated Release of Favorable Minimum Wage Study.” Seattle Weekly. July 27, 2017. Accessed April 06, 2018. http://www.seattleweekly.com/news/emails-show-mayors-office-berkeley-economist-coordinated-release-of-favorable-minimum-wage-study/.

- Tankersley, Jim. “Here’s a Really, Really, Ridiculously Simple Way of Looking at Minimum Wage Hikes.” The Washington Post. May 05, 2016. Accessed April 06, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/05/05/heres-a-really-really-ridiculously-simple-way-of-looking-at-minimum-wage-hikes/?utm_term=.2d6bb01e838c.

- Manheim, Jarol. “The Emerging Role of Worker Centers in Union Organizing: An Update and Supplement.” Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America. 2017. Accessed April 06, 2018. https://www.uschamber.com/sites/default/files/uscc_wfi_workercenterreport_2017.pdf.

- Person, Daniel. “Emails Show Mayor’s Office and Berkeley Economist Coordinated Release of Favorable Minimum Wage Study.” Seattle Weekly. July 27, 2017. Accessed April 06, 2018. http://www.seattleweekly.com/news/emails-show-mayors-office-berkeley-economist-coordinated-release-of-favorable-minimum-wage-study/.

- Center for Organizational Research and Education. “Economic Policy Institute.” Activist Facts. Accessed April 09, 2018. https://www.activistfacts.com/organizations/516-economic-policy-institute/.

- Covert, Bryce. “Democrats Are Now All on Board with a $15 Minimum wage.” ThinkProgress. April 26, 2017. Accessed April 09, 2018. https://thinkprogress.org/democrats-15-minimum-wage-bill-f7631a21ec24/.

- “What We Can Learn from the Fight for $15.” Economic Policy Institute. June 30, 2016. Accessed April 09, 2018. https://www.epi.org/event/what-we-can-learn-from-the-fight-for-15/.

- Bragg, Chris. “$15 Wage Research Fogs Issue as Labor, Business Groups Push Studies.” Times Union. March 24, 2016. Accessed April 09, 2018. https://www.timesunion.com/tuplus-local/article/15-wage-research-fogs-issue-as-labor-business-7004332.php.

- Bragg, Chris. “$15 Wage Research Fogs Issue as Labor, Business Groups Push Studies.” Times Union. March 24, 2016. Accessed April 09, 2018. https://www.timesunion.com/tuplus-local/article/15-wage-research-fogs-issue-as-labor-business-7004332.php.

- Person, Daniel. “The City Knew the Bad Minimum Wage Report Was Coming Out, So It Called Up Berkeley.” Seattle Weekly. June 26, 2017. Accessed April 09, 2018. http://www.seattleweekly.com/news/seattle-is-getting-an-object-lesson-in-weaponized-data/.

- Mair, Aaron. “America Crippled by Low Wages.” Times Union. April 14, 2016. Accessed April 13, 2018. https://www.timesunion.com/tuplus-opinion/article/America-crippled-by-low-wages-7246614.php.

- Aroneanu, Phil. “The Fight for $15 Is the Fight for a Livable Planet.” 350.org. Accessed April 13, 2018. https://350.org/the-fight-for-15-is-the-fight-for-a-livable-planet/.

- Lerer, Lisa, and Jake Pearson. “Clinton Supports ‘fight for 15’ Movement, but Backs a Lower, National Standard.” PBS. April 04, 2016. Accessed April 13, 2018. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/clinton-supports-fight-for-15-movement-but-backs-a-lower-national-standard.

- Watson, Michael. “Under New Management: Pushing Back Against Big Labor.” Capital Research Center. November 15, 2017. Accessed April 09, 2018. https://capitalresearch.org/article/under-new-management-pushing-back-against-big-labor/.

- De Lea, Brittany. “Fight for 15 Strikes Dramatically Decline in 2017, New Research Shows.” Fox Business. August 10, 2017. Accessed April 09, 2018. https://www.foxbusiness.com/politics/fight-for-15-strikes-dramatically-decline-in-2017-new-research-shows.

- Gupta, Arun. “Low-Wage Workers’ Struggles Are About Much More than Wages.” Portside. April 21, 2015. Accessed April 09, 2018. https://portside.org/2015-04-21/low-wage-workers-struggles-are-about-much-more-wages.

- Associated Press. “Fast-food Protests Shift Focus to ‘wage Theft’.” Crain’s Chicago Business. March 18, 2014. Accessed April 09, 2018. http://www.chicagobusiness.com/article/20140318/EMPLOYMENT/140319722?template=printart.

- De Lea, Brittany. “Fight for 15 Strikes Dramatically Decline in 2017, New Research Shows.” Fox Business. August 10, 2017. Accessed April 09, 2018. https://www.foxbusiness.com/politics/fight-for-15-strikes-dramatically-decline-in-2017-new-research-shows.

- Greenhouse, Steven. “Fast-Food Workers in New York City Rally for Higher Wages.” The New York Times. November 29, 2012. Accessed April 09, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/30/nyregion/fast-food-workers-in-new-york-city-rally-for-higher-wages.html?pagewanted=all.

- Higgins, Sean. “Democrats Officially Introduce $15 Minimum Wage Bill.” Washington Examiner. May 25, 2017. Accessed April 09, 2018. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/democrats-officially-introduce-15-minimum-wage-bill.

- “State Minimum Wages | 2018 Minimum Wage by State.” National Conference of State Legislatures. January 2, 2018. Accessed April 09, 2018. http://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/state-minimum-wage-chart.aspx.

- Saltsman, Michael. “New York City Wants to Supersize the ‘Fight for $15’.” The Wall Street Journal. May 19, 2017. Accessed April 13, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/new-york-city-wants-to-supersize-the-fight-for-15-1495235426.

- “Richard F. Griffin, Jr.” National Labor Relations Board. Accessed April 9, 2018. https://www.nlrb.gov/who-we-are/general-counsel/richard-f-griffin-jr.

- Watson, Michael. “Under New Management: Pushing Back Against Big Labor.” Capital Research Center. November 15, 2017. Accessed April 09, 2018. https://capitalresearch.org/article/under-new-management-pushing-back-against-big-labor/.

- Morath, Eric. “Q&A: SEIU President on Lessons for Labor in ‘Fight for $15’.” The Wall Street Journal. May 23, 2017. Accessed April 13, 2018. https://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2017/05/23/qa-seiu-president-on-lessons-for-labor-in-fight-for-15/.

- Gupta, Arun. “Fight For 15 Confidential.” In These Times. November 11, 2013. Accessed April 13, 2018. http://inthesetimes.com/article/15826/fight_for_15_confidential.

- Luna, Nancy. “McDonald’s and NLRB Reach Settlement in Joint-employer Case.” Nation’s Restaurant News. March 19, 2018. Accessed April 13, 2018. http://www.nrn.com/workforce/mcdonalds-and-nlrb-reach-settlement-joint-employer-case.

- Morrison, Aaron. “AP Exclusive: ‘Strike for Black Lives’ to highlight racism”. Associated Press. July 8, 2020. https://apnews.com/d33b36c415f5dde25f64e49ccc35ac43.

- Morrison, Aaron. “AP Exclusive: ‘Strike for Black Lives’ to highlight racism”. Associated Press. July 8, 2020. https://apnews.com/d33b36c415f5dde25f64e49ccc35ac43.

- Chiaramonte, Perry. “SEIU’s Fight for $15 May Be on ‘chopping Block,’ despite Spending $90 Million.” Fox News. March 31, 2017. Accessed April 16, 2018. http://www.foxnews.com/us/2017/03/31/seius-fight-for-15-flop-despite-spending-90-million.html.

- Jamieson, Dave. “Union Behind The ‘Fight For $15’ Cuts Funding For Fast-Food Campaign.” The Huffington Post. April 03, 2018. Accessed April 16, 2018. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/union-behind-the-fight-for-15-cuts-funding-for-fast-food-campaign_us_5abfe925e4b055e50ace1a2d.

- Redmond, Sean P. “Fight for $15 Reappears.” U.S. Chamber of Commerce. February 14, 2018. Accessed April 16, 2018. https://www.uschamber.com/article/fight-15-reappears.

- Donnelly, Grace. “This Is How Many Americans Will See a $15 Minimum Wage By 2022.” Fortune. June 30, 2017. Accessed April 16, 2018. http://fortune.com/2017/06/30/15-minimum-wage/.

- Berman, Richard. “Honey, I Shrunk the Union.” The Wall Street Journal. April 11, 2017. Accessed April 16, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/honey-i-shrunk-the-union-1491951511. See also Service Employees International Union, Annual Report of a Labor Organization (Form LM-2), 2017, Item 20, for 2017 year-end information.

- Morath, Eric. “Labor Movement Spends Millions to Boost Wages for Workers Who Don’t Yet Pay Dues.” The Wall Street Journal. May 23, 2017. Accessed April 16, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/labor-movement-spends-millions-to-boost-wages-for-workers-who-dont-yet-pay-dues-1495537201.

- Lerner, Kira. “Labor Unions Are Trying to Take Back Politics in the Midwest.” ThinkProgress. September 3, 2017. Accessed April 16, 2018. https://thinkprogress.org/labor-unions-midwest-eeae1de51e34/.

- Greenhouse, Steven. “Fight for $15: The Strategist Going to War to Make McDonald’s Pay.” The Guardian. August 30, 2015. Accessed April 16, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/aug/30/fight-for-15-strategist-mcdonalds-unions.

- Lewis, Cora. “A Top Labor Executive Has Resigned After Complaints About His Relationships With Female Staffers.” BuzzFeed. October 23, 2017. Accessed April 16, 2018. https://www.buzzfeed.com/coralewis/seiu-courtney-resigns?utm_term=.psD3JrKgb8#.wrLEadqZYR.

- McMorris, Bill. “Ex-SEIU Employee Says Two Union Supervisors Sexually Harassed Her.” Washington Free Beacon. October 19, 2017. Accessed April 17, 2018. http://freebeacon.com/issues/ex-seiu-employee-says-two-union-supervisors-sexually-harassed/.

- Eidelson, Josh. “SEIU Ousts Senior Leaders for Abusive Behavior Toward Women.” Bloomberg News. November 2, 2017. Accessed April 17, 2018. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-11-02/seiu-ousts-senior-leaders-for-abusive-behavior-toward-women.

- Eidelson, Josh. “U.S. Labor Leaders Confront Sexual Harassment in Top Ranks.” Bloomberg BusinessWeek. November 7, 2017. Accessed April 17, 2018. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-11-07/u-s-labor-leaders-confront-sexual-harassment-in-their-top-ranks.

- Esposito, Stefano, and Mitchell Armentrout. “Union Organizer Fired from ‘Fight for 15’ Minimum Wage Group.” Chicago Sun-Times. October 25, 2017. Accessed April 17, 2018. https://chicago.suntimes.com/news/union-organizer-fired-from-fight-for-15-minimum-wage-group/.

- Pethokoukis, James. “It’s Not Just Center-right Economists Who Are Skeptical of the $15 Minimum Wage.” AEI. June 9, 2016. Accessed April 17, 2018. http://www.aei.org/publication/not-just-right-economists-skeptical-of-15-minimum-wage/.

- Employment Policies Institute. “Survey of US Economists on a $15 Federal Minimum Wage.” MinimumWage.com. November 18, 2015. Accessed April 17, 2018. https://www.minimumwage.com/2015/11/survey-of-us-economists-on-a-15-federal-minimum-wage/.

- Peterson, Eric. “Seattle Progressives Stick Their Heads in the Sand on Minimum Wage.” National Review. July 20, 2017. Accessed April 17, 2018. https://www.nationalreview.com/2017/07/seattle-minimum-wage-study-city-cut-funding-when-it-didnt-results/.

- Ehrenfreund, Max. “Analysis | A ‘very Credible’ New Study on Seattle’s $15 Minimum Wage Has Bad News for Liberals.” The Washington Post. June 26, 2017. Accessed April 17, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/06/26/new-study-casts-doubt-on-whether-a-15-minimum-wage-really-helps-workers/?utm_term=.45dd5bd5e1a8.

- Person, Daniel. “The City Knew the Bad Minimum Wage Report Was Coming Out, So It Called Up Berkeley.” Seattle Weekly. July 27, 2017. Accessed April 17, 2018. http://www.seattleweekly.com/news/seattle-is-getting-an-object-lesson-in-weaponized-data/.

- Moberg, David. “Fight for $15 Organizers Tell SEIU: We Need $15 and a Union.” In These Times. August 14, 2016. Accessed April 17, 2018. http://inthesetimes.com/working/entry/19387/breaking_fight_for_15_organizers_tell_seiu_we_want_15_and_a_union.

- Gupta, Arun. “EXCLUSIVE: Some of SEIU’s ‘Fight for $15’ Workers Aren’t Unionized — and Don’t Make $15 an Hour.” Raw Story. August 13, 2016. Accessed April 17, 2018. https://www.rawstory.com/2016/08/exclusive-some-of-seius-fight-for-15-workers-arent-unionized-and-dont-make-15-an-hour/.

- Diaz, Jaclyn. “Fight for $15 Workers Unionize Amid SEIU Changes.” Bloomberg BNA. November 30, 2017. Accessed April 17, 2018. https://www.bna.com/fight-15-workers-n73014472639/.